The memoir of the artist is often considered to be a compelling story. For those who are interested in the private lives of cultural figures, specifically those who have entered into the annals of history, a book by anyone of note lends a palimpsest of dimensions to our current understanding of who they were, and how their own model can act as a symbol for our shared self-knowledge. This is what constitutes the basis for Rob Mango’s memoir, a story worth telling about all the experiences in his life, up until now, that have built him as a person and ultimately as an artist. The voice that does the telling is inimitably his own, virile and dynamic, the voice of an athlete who became an artist, and for whom the physical environment and the physical bodies around him were a continual source of inspiration, reflecting personal and mythical realities. Place also has been an important part of Mango’s story, specificallly the Lower Manhattan area which only since he lived there has come to be known as Tribeca, and has emerged out of history and created its own myth. Lastly, this is a book about his relationships, about the meetings that precipitated them, and about what happened in his life because of them. Lastly it’s a story about the progress of a man from child to man, including all the roles that it encompasses, such as father, husband, provider, and role model, all wrapped around the soul of an artist.

Everyone is responsible for their own myth. But most people are passive about the truth. Not Rob Mango. Since an early age he has been a competitive runner, and the discipline needed to keep in shape is a form of self-evident knowledge that has guided his dedication to art as well. 100 Paintings runs us through the artist’s life in the last three decades, starting in Chicago where he grew up, while running competitively, attending the School of the Art Institute, and his early inspirations and challenges. Mango’s story begins when he is young, growing up on the south side of Chicago, beginning his education in the world of ideas and of artistic self-expression. He visits The Art Institute when he is 14 and sees a painting by Larry Rivers that sets his mind on fire. Soon afterward he chances to meet the famous Dada agent provacateur Marcel Duchamp, who signs a poster for him using his famous pseudonym, Rrose Selavy, inspired by the word games of Gertrude Stein and e.e. cummings. He is inculcated in the ways and means of contemporary poetry by his mother, who reads aloud at the breakfast table. He applies and is accepted at The School of The Art Institute, later completing his graduate studies at The University of New Mexico. Much of this is a sketch, a preamble to his life in New York, which is where the story truly begins in earnest.

Mango’s story is prefaced by a crisis, an unlikely point of origin but one innately endemic to an artist’s career. After working and struggling for years, he finally gets his time in the spotlight when a young art dealer named Valerie Dillon offers him not only a solo exhibition but gallery representation. The gallery director is an intense individual, who pressures him to make endless versions of a single set of figures, shortens his solo exhibition to organize a group show of other gallery artists, ignores the rest of his ideas and works, and sells his work for much less of a percentage than he has become accustomed to when representing himself. When a sale goes awry, she snaps and returns all his work en masse. His story begins with the arrival of the works and the state of mind Mango experiences as witnessed by his family, a “what now?” moment punctuated by awkward silence. Yet despite this circumstance, this one moment of freefall, 100 Paintings is a story about success on one’s own terms. This moment is recalled as if to say “so what!” and move on.

The first few chapters deal with his youth and his origins as an artist. He grows up on the south side of Chicago, with a father who is an industrial designer and a mother who he describes as a “self-educated reader.” Mango comes to the idea of being an artist from the age of 14 when he views a painting by Larry Rivers on a visit to The Art Institute of Chicago.

“From that moment on, painting for me was breathing. I filled volumes of portfolios and rooms with canvases, objects and drawings. Many of these works have survived, but I did not consider myself good enough to sign a painting (In spite of my vociferous objections, my wise and caring father often added my name in the lower right hand corner) (page 39).”

Mango goes through several influences including Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Surrealism. Though he remains devoted to the work of Larry Rivers and Jasper Johns in particular, he lost interest in others because they in turn lost touch with what originally inspired them and became figureheads for either a political stance or the partying elite. Ultimately he is inspired by Mercel Duchamp (whom he met when Mango was 16) and by the sculptural accomplishments of he and his fellow Surrealists.

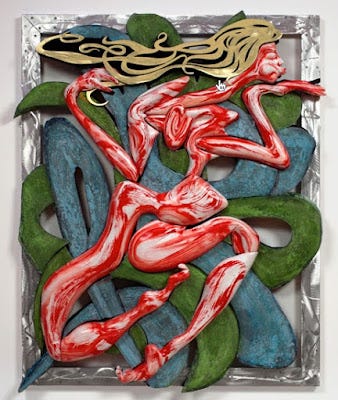

“To embody the surreal, of course, is a dicey undertaking. Surrealism’s domain is the mind’s deepest recess, where the death instinct resides, along with sex: Surrealism takes much of its power from Eros and Thanatos. I had existential needs that surrealism spoke to, but I wanted to transform those needs and insights from literature and theater into an art object that would live on the wall (page 47).”

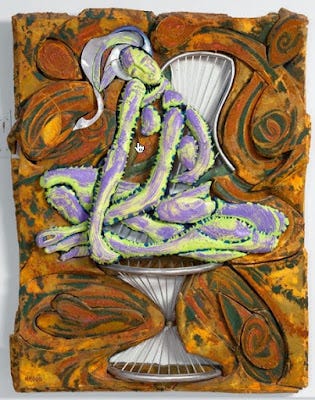

The artist accumulates a visual library of persona based mythologies, and Mango is no different. His myths form a history of their own, and a quality of formal reckoning that can only be answered by an engagement with what he has accomplished. Starting with his Dadaist assemblages (1975-1988), we have him confronting models of creativity that hearken back to the turn of the century, creating a conversation with idols of mystery like Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Jean Tinguely, and pitching him completely into an endeavor that fuses sculptural hermeticism with cerebrality. He is overtly going against the grain of the education in classical painting he received at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, putting off his inevitable return to the role of the great painter. The assemblages take of part of his studio practice until the mid-Eighties, at which point he switches over to panting while tinkering with one last piece until 1988.

Influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s “Large Glass,” these Dadaist sculptures combined painting, drawing, working lights and moving parts, including light sources. They were like Wunderkammers. Yet what at first may have seemed a tribute to his creative forebears and an experiment in widening the context for his own artmaking, might have soon seemed more like a gimmicky agenda for big city art world notoriety. These sculptures excavated some part of him, but they did not reflect his relationship with the vibrant environment unfolding all around him. It was on his frequent runs around the city that he received the majority of his stimuli to bring the city into his work, and the only way to do that was to paint.

One aspect of Mango’s life that would otherwise receive little regard is his background as a competitive runner. In fact it is something very central to his identity that has shaped him as a person and has even become a part of his creative process. From his teen into his late 20’s Mango ran in and won many regional and even national competitions as a middle distance runner. He came very close to qualifying for an Olympic team at one point, and it was his choice not to pursue that goal further that led him to get behind his other aspiration as an artist. In painting as in running there is no perfect score, only a personal best. However, once Mango had given up his pursuit of running as a competitive sport it still remained a part of him and became a way of encountering, musing, and reflecting his themes and subjects as a painter. In 100 Paintings we often see Mango running. He does it every day. It jump starts his brain and gets his blood flowing. He has been running for years and so does not need to focus on his physical activity, but can instead spend his time looking around him, seeing the city for what it is, a vast physical environment, constantly in flux and constantly in motion, all of its parts and participants simultaneously actual and symbolic.

In one section of the book titled “Sprinting the Streets of New York City” he describes the role that running has in his artistic process. Not merely a self-expulsion from the intellectuality of the studio, running provides Mango with an equally intense state in which he can encounter, muse upon, and be inspired by what surrounds him. The forms that occur in painting exist in the world, and the city itself is a world made of forms that are constantly being constructed, reorganized, and justified. It’s as if a forest were grown, torn down, and re-harvested every time one looked out the window. The city is, to Mango, inspiration personified, and running is the best way to interface with it.

“My runs provided the mental state in which my paintings were visualized. I saw the evolution of future paintings with all their complex internal detail. These were works of art I had yet begun or those still in progress. They were visualized and hovering in my mind, waiting for a canvas to land on, like so many jets at JFK. I switched pictures on and off in my mind with facility. By the late 70’s , the infusion of oxygenated blood to my brain was something I’d done on a consistent basis for more than a decade. Invention was fueled by extreme physical output (page 78).”

Physicality has always been a vibrant aspect of Mango’s work, and he has chosen figures to represent different ideals of the physical, even while they also served as metaphors for a foil for the artist, like his Samurai and his Jester paintings. Physicality is both a metaphor and a presence, an ideal and a passion. As a classically trained painter, the uses and roles of the human body have always been very important to him.

Place emerges as a constant theme in Mango’s life, and subsequently in his art. He is in his own words a “pioneer” of the Manhattan neighborhood now known as Tribeca. It is here that he first settled and here he has stayed, made his art, raised a family, and made all of his other important relationships. Tribeca was a product, to some degree, of neighboring Soho, an area once lain desolate, used mainly as storage, and inhabited by few actual residents, the landscape dotted here and there by a bodega here, a deli there. Though many artists moved there at the same time, it remained a no-man’s land to most others, and was surrounded by a vast landfill off the side of the West Side Highway, and to the south sat the recently constructed World Trade Center. Several of his most epic paintings have had the city itself as either their immediate subject or as a fabric if reality. Though there were certainly precursors, the first of these that Mango talks about is RETURN TO THE CITY (1985), which renders the landscape of the city as resembling an archeological excavation. Mango call it “My first attempt to capture the most difficult subject in my imagination’s domain.”

I had just built and stretched a 60 by 84 inch canvas and stained it with pale umber primer, an earthen hue. I did so because there was dirt below the streets, tunnels and century-old layers of crumbling brick foundations….I wanted to create a picture illustrating the dominant visual features of lower Manhattan as body parts; what lay below the streets would represent the unconscious mind. Like the psyche obscured and unseen within us, the unconscious smolders under the asphalt, its hidden power animating the surface, like the rumble of the subways under your feet or the scalding manhole covers, apparent on any day in New York. Manhattan had become my muse, and she was almost too much to handle. But for one who craved work, with years of racing wins behind me, that was the only game worth playing (page 77).”

New York City in the 1970’s had one foot in the past and one in the present, which is to say that it was a vibrant city mired in its own ruin. The romance of its past was still there if one squinted. The neighborhood that would soon become Tribeca was one of the oldest in the city, containing mainly loft buildings dating to the mid 1800’s. Many of these were vacant and held storage. Rob Mango’s presence, with a street level studio window must have been quite the curiosity to tradesmen and property owners alike. He was one of the most visible members of a mostly shadow community of artists who had not found likewise space in an already heavily colonized Soho. They became the founders of the Lower Manhattan Loft Tenants Association, comprised almost completely by his neighbors in the Washington Market district. The reality of city living is that the city itself is a complex organism constantly undergoing flux and change. Generations have passed over the same ground that we walk today, a century or more removed, and there is little left to mark their passing except for an old building or the name on a street sign. So much the better. The city grinds its past like old bones, into a fine dust that coats everything. If one wakes early enough and chances to walk down a street in a neighborhood such as Tribeca, squinting just enough, one sees the past clearly, not through a film of myth, but as a real place where people struggled and strived, where generations and families staked a claim the future of which was unsure. This was the reality into which tenants of lofts in Tribeca were thrust. Mango has made his way with the full knowledge that not only could be accomplish so much as an artist, and subsequently life his life as he saw fit, but that he might, as Walt Whitman said, contribute a verse.

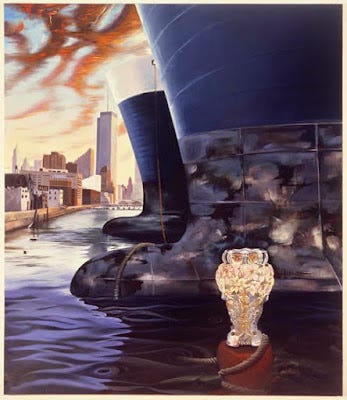

Another role that Mango had during his lifetime was that for a period of five years, with the unstinting support of a patron, he ran a gallery called Neo Persona located just around the corner from where he lived, and it was this singular activity that not only connected him to every other artist living in Tribeca, of those he exhibited, but it was also a driving force behind the manifestation of many of his own paintings, which had to be made despite the full time pressures of being an impresario, gentleman director, and in his own way a professional visionary aiming to raise the bar not only for local artists and their potential collectors, but for the image of Tribeca itself. Not only did Mango unite the community of like minded artists around the locus of his own curated exhibitions, but the ferment of tangentially presented talents created a wellspring for his own creativity, forcing him to stretch himself beyond comfortable boundaries. One work that resulted from this internal pressure was VESSELS, which began as an epic depiction of Lower Manhattan along the Hudson, where he often saw immense ships moored along piers, tilting in the slight current, bound for parts unknown. He wanted to show their grandeur and age next to the new modern buildings of the Financial district abutting Tribeca, but something else emerge from his perspective, something glittering and special. He painted a crystalline vase standing atop one of the stanchions where the ropes that held the boats fast would be tied. This was by no means a real thing, it was almost like a lost antique that could be a fortune teller’s ball, an urn carrying ashes, or a good luck charm. The viewer’s attention would naturally turn from the distant horizon, to the looming boats, and over to this mystery that glittered in the last rays of dusk. It is as if Mango is creating a mysterious narrative in which the idiosyncracies of dramaturgy run smack up against a battle between the story of the future and the story of the past.

In recent years, Mango has devoted himself progressively to a series of paintings depicting women in impossible poses. These range from the formal to the mundane but the essential femaleness of their outward appearance and the struggle to do it justice are achieved by a variety of effects, as if Mango were attempting to alchemically translate the real woman into an ideal one and back into a new form of the real. For the sculpted canvases, which had their origin the first moments of clarity following the return of his canvases from Dillon, when he decided to rip them to shreds and reutilize these damaged goods by placing them over a base constructed from a frieze of bodily forms, Mango added a dozen years later a series of dramatizations of intimate moments caught on the fly while sitting in area cafes. Each addition to his oeuvre in both of these cases followed a crisis. The second rupture was in two parts” 9/11 reduced the World Trade Center to a cemetery, and the surrounding neighborhood, once the playground of artists and yuppies alike, had now become a dead zone. Few New Yorkers except those living within the bounds of Tribeca or near enough to see what happened on that day, and be forced to live in its aftermath, can understand the emotional consequences that followed. Yet Mango decided to stay home, to make the best of it, and pitch in wherever he was needed.

The crisis of the 9/11 period, and the years following it were spent both participating in the struggles of his community and focusing upon regaining the authority of his own life, both in terms of family unity and in creativity. As anyone who has witnessed a great tragedy, and has their life subsumed by it can attest, there is more than a physical rebuilding involved. Emotional violence breaks apart our lives on a grand scale, shattering the peace of our days, and creating eddies of doubt in every corner. This is what Mango experienced. It led him out of his studio, or rather our of the sacred space he had fed for so many years, into the street, back into the world of bodies, where he could find new ferment.

It’s difficult to fully encompass all the events that occur in 100 Paintings. Many of them are meetings between the artist and the various people who are to become his friends and patrons and who each lead him into a new experience that will expand his consciousness, his facility in expressing himself to others about his creative endeavor, and the very ‘life of the mind’ that makes him who he is. Some of the people he meets are famous, and some are people who pass the front window of his studio and enter to engage him in discussions about the work, often leading to a sale. These are not just opportunities for income, they are the beginning of friendships, aesthetic relationships that will inform his thinking about the minds of others, and how he can relate to them. This is another of Mango’s various talents: he can talk to anyone about his art, his mind, and his life, and never appear haughty or esoteric. Something seems to happen when new visitors gaze upon his work, a fusion of fascination with internal reasoning. Likewise I feel that is what is present in his memoir. 100 Paintings is presented as an appreciation of what is most valuable in life. Mango is neither interested in a mere parable, nor is he interested in promoting his own myth. The paintings do that successfully enough. His story is his voice, speaking about the character, dimensions, and details of his own life in the last few decades. The life of an artist, for whom 100 Paintings is a good idea, is just par for the course. The finish line is nowhere in sight.