An Appetite for Disruption

The Legacies of Dave Tourjė

Certain kinds of people are more apt to disrupt. They do it just by being themselves; they do it by avoiding traditional roles; and they do it by being successful in more than one field of endeavor. History calls them polymaths. Dave Tourjė is just such a person. He’s had a life of accomplishments, and they all came to a head when, at the end of 2023, he was presented with an award from the Los Angeles Business Journal’s annual celebration as “Disruptor of the Year'' for his leadership of Alpha Structural, through which he innovated means of reinforcing architectural structures for over 30 years. Tourjė’s Innovation goes hand in hand with a progressive attitude that shakes up traditional models which led him into his second simultaneous business innovation–his placement of women in instrumental roles within a previously all male-oriented business. Tourjė ’s interests are diverse, from music and art to his foundational support of the renowned Chouinard School of Art, to his artistic fellowship and brotherhood with the California Locos, to furniture, to film, to graphic design, and to his business and design innovations with Alpha Structural. This essay will trace the history of attitudes developing into forms that have played out his complex vision in a myriad directions, how they originated, how they grew, and how they developed him into the disruptor that he is today.

The disruptor emerges from a history that was in some ways disrupted itself. Movement from one place to another; interests and disciplines shaped by new friends in new places; exposure to visionary creative ideas and people as well as practical, industry based ones. The mind of the disruptor reels in the swath of possibilities, and it rights itself among alternating sources connecting to drives and aspirations. Tourjė has been the product of just such an evolution, so he naturally alternates in his focus while remaining rooted in disruption. We can speak of his childhood and youthful upbringing in generalized terms. They are important years that helped set the model for who he is today. A change in where he lived, of the sort of people he met and the specific cultural experiences that became available to him in altered circumstances, all augured a degree of surprise and personal growth through the struggle to learn and adapt. We can state what we know of the facts with some certainty, given their importance.

A person of accomplishment follows a trail of their own discernment, yet all are shaped by experiences that mold their minds, that cannot be evaded. Call this fate. Heraclitus, a Persian philosopher from the 5th century, stated that character animates that power that controls the destiny of individuals. In this respect, Dave Tourjė was fated to be a disruptor. We’re here to track his path and enumerate the dimensions of it. Tourjė has creations across a broad swath of creative endeavor (music, furniture design, painting, sculpture, graphic design, film direction), but his talents have also been organizational, coordinating and marketing the image of the California Locos—a collective of five artists, each acclaimed in different ways and working in complementary cross purposes to advance cultural values and idiosyncratic aesthetics out of their combined life experiences central to the Los Angeles gestalt. Tourjé’s involvement in the founding and conservatorship of the Chouinard Foundation in 1999, beginning with the improbable acquisition and restoration of Nelbert Chouinard’s cultural landmark home, and its related connoisseurship and benefit to young and disenfranchised artists today. There are other aspects to Dave Tourjė yet. He is a labyrinth of intention, and his intentions do not float about, but become form. He’s all about putting it out there.

Tourjė’s mother was from Mexico City; so he lived there for a time and would travel there to visit family from a young age. While soaking up the dichotomies and similarities to Los Angeles, surrounded by a culture especially rooted in its own values, Tourjė regularly encountered the work of Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose public murals became a strong influence upon him. Like Tourjė, Siqueiros also had a shared history with Los Angeles. Siqueiros had been invited to teach at the Chouinard Art Institute in 1931, where he had also painted his first iconoclastic public mural that was forgotten and lost, until ironically, Tourjė with a group of artists including Luis Garza, Nob Hadeishi and Jose Luis Sadano later rediscovered it in 2005. The influence of such important artistic works were essential to Tourjė’s self-identification as an artist, a role that attracted him from a very early age, as he was developing his drawing skills all throughout his younger years, and was winning school prizes for his creative accomplishments. The murals did not specifically inspire him to likewise become a muralist, but their combination of style with socially-oriented content became infused into his character. He began to realize the artist was not by his very nature always an outsider, but could be a unifier. That spark led to many collaborative ventures of which we will also speak.

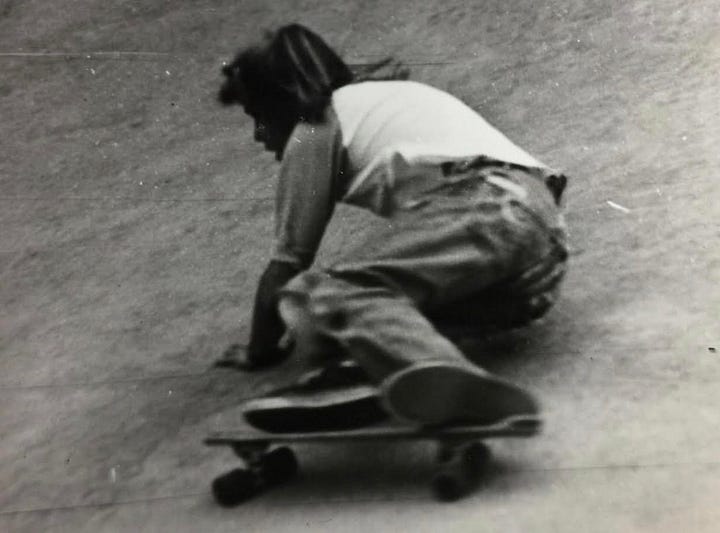

Another early influence upon his burgeoning identity and appetite for disruption was the street culture of skateboarding. It has to be understood that the specific urban sphere produced by the organic growth of Los Angeles into divergent communities with no central organization has led to a certain frontier mindset into which cultures of rebellion have easily flourished. Surf/Skate culture represented an option for disenfranchised youth to exercise their individualistic natures. The free ranging activity of groups of skaters, searching for opportunities to engage with the physical environment, in some cases breaking with established communal versus private boundaries, and using the discipline of mastery over the use of the skateboard, they would develop certain operational skills and degrees of confidence that would allow them to progress through adolescence into a sense of communal identity. It also establishes their familiarity with the range of environments that combine to represent a world they can know. One can hardly imagine how many levels this activity represented an expansion in a young boy’s world view and self-regard. The activity itself advanced Tourjė’s willingness to take risks, and to view the risks inherent in the activity as a worthwhile learning experience. The illegal quality of skateboarding at the time involved using people’s private pools as a site for experimentation, which occurred while in illegal trespass. It was a “rebel sport” and very dangerous wherein concussions and broken bones were commonplace. So this was a constant threat that could happen at any moment- along with going to jail for various reasons including truancy. Mastering the skills necessary to prevail against the risks was a good preparation for later in life, evolving state of mind, and guided him in the world view of the disruptor.

One of the creative anchors in Dave Tourjė ’s life has also been music–not only for its representative discipline, but for how it has allowed him into a meeting of the minds, into creative congress with others, and in forming various bands and working on specific musical projects. Tourjė has expanded his creative repertoire into various local subcultures that link to his past, especially the LA Punk Scene of the 1980’s, when he was part of numerous bands including The Dissidents (1984-86), whose hard work garnered them a “Best of the Unsigned Bands” award on the MTV Music Awards as well as rotation on the Basement Tapes in 1985. His “new” group is Los Savages, which started up in 2014 and is still going strong, composed of seasoned veterans Ian Espinoza (Mighty Hornets), Bryan Head (Foreigner) and Jim Grinta (Michael Jackson).

Tourjė has fulfilled many roles of the creative individual. Early notoriety came from furniture design in the mid 1980s, as he combined his construction experience in reinforced concrete and steel, with Bauhaus inspiration. He was coming out of a period in his life when there had been rapid change. He had just built his first hillside home and moved his young family there in 1987, close to his old home in Highland Park. He was hanging out with new people, was involved in the building construction field, and he was recently married to his wife Linda. Life, though positive, can have a way of ganging up on us. When change comes, it arrives in force. We start putting a particular energy out there and suddenly we’re caught up in currents that transform us. Reining in these currents is the job at hand. Harnessing these forces leads to personal growth on a major scale. Furniture was perhaps an unheralded mode in the expected drives of the creative, but it emerged from his work in construction–an imagining of the sorts of objects that would fill such diverse living spaces, and the challenge to create something not only functional, but new.

The type of furniture Tourjė started making was influenced by design trends in the Los Angeles area, but he didn’t follow them blindly. He found his own unique place in it. Because he was working in construction, he had access to a machine shop where he could shape the heavy materials that most interested him: cast concrete, steel, and industrial grade glass. What Tourjė wanted was a departure from the predominant style of the Eighties, which was a sort of Italian slickness, originating from Milan. Either that or The Memphis style with Peter Shire. Tourjė was interested in a form of sophisticated Brutalism that juxtaposed well with anything from mid-century modern in Palm Springs to Chateau style in Beverly Hills, and more. Personal favorites from among the 200 individual objects created and sold between 1987 and 1992 include the aptly named “Tourjė Chair” (1987) and “DTBH1” (1991). These works continue to have a life of their own. Tourjė Chair was recently on view in This Is Not A Chair at The Claremont Lewis Museum of Art from February 2 to April 21, 2024. “DTBH1” was a collaboration with Tourjé’s “oldest friend in Art,” the acclaimed sculptor Brad Howe: a chaise lounge made of concrete, stainless steel and aluminum, for which Howe created the interior structure of the overall sculptural piece. One work, “Corn Plenty,” a dining table with a painting as its top, and chairs with a single stainless spike as their back, was featured in a major exhibition at The Orange County Museum of Art in 2001. His landmark aesthetic remains important and his work has been exhibited in numerous museums around SoCal and sold internationally from LA to Toronto, Cologne to Paris.

Concurrent to his furniture practice Tourjė was also heavily involved in making paintings which he ascribed to a primitive or “punk” aesthetic that captivated him for over a decade, having lived in the LA Punk scene itself. Though Tourjė had been involved in drawing from an early age, and was possessed of advanced drawing skills, he was fascinated by a method that would deny them–that was speciously imperfect. Like cave paintings or children’s drawings in crayon. He realized a great variety of imagery in this way, initially trashing his formal roots. Tourjé was all the while evolving, and his natural talents lending toward drawing in an advanced manner had to eventually emerge. Focusing upon material application, building more sophisticated gestures, and actualizing narratives that progressively relied upon the illusion of depth and a focus on his characters. The artist’s development, though intense, is not always procedural, but circular. One faces a particular set of ideas and works them out until they are either successfully realized or given up. Sometimes what is required is a completely alternative perspective, and the utilization of new methods and disciplines. Over time Tourjė evaluated his work, and decided that it was imperative for him to establish new standards. He worked on his drawing skills and took from certain regional styles, mixing them together with antique handicrafts that he purchased while on his travels. He evolved “reverse painting” from the ‘80s, ending doing large-scale works on acrylic glass. What resulted were his now signature works such as “Falling Dream I” (2002), “Terminal Elevation Principle Volume 2” (2011) and “2 Late 4 Luck” (2014). These works range in scale from two feet square all the way up to 10 feet square. Select parts of them employ distinctly illustrative figures consisting of a metaphoric quality running the gamut from the dynamism of celebration to echoes of mortality. Sustained acts of cultural heroism flutter about in an ever darkening world, reflecting an indomitable inner grace.

Despite the focus required to sustain creative rigor and its resulting successes both in the studio and in galleries and museums, Tourjė recognizes that individual disruption cannot suffice. The artist is a product of history, and community. This extended legacy of the art community in Los Angeles was addressed by Dave Tourjė in his establishment of The Chouinard Foundation, a nonprofit begun after the specific circumstance he found himself in following his purchase of a home in South Pasadena, which unbeknownst to him, was the original home of a famous but now obscure cultural figure named Nelbert Chouinard. She was the founder of an important art school that was in operation from 1921 to 1972. Her school was important on several levels. For many it was a haven for creatives who didn’t fit in anywhere else, such as Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell and numerous others. Chouinard allowed many of her students the opportunity to attend with her personal backing, which is to say that she did not charge them for the classes, seeing in them a drive and a talent that deserved support. All the other members of the California Locos besides Tourjė had attended classes there or graduated from its program. Her institute had provided essential educational sustenance to successive generations of freethinking artists. When Tourjė realized what he had bought, he immediately considered its value, and decided that it was likewise a legacy worthy of further support. After the initial discovery, it took a year or so to for the official nonprofit entity, and then assemble the board, which consisted of mostly Chouinard graduates like Doris Kouyias, Chuck Swenson, plus all of the Locos including John Van Hamersveld, Norton Wisdom, Chaz Bojórquez, and Gary Wong. They went on to establish educational initiatives for creatives among underserved youth. This concentrated and related history of the school itself, was the focus of the documentary film titled CURLY (2013), which Tourjé executive produced.

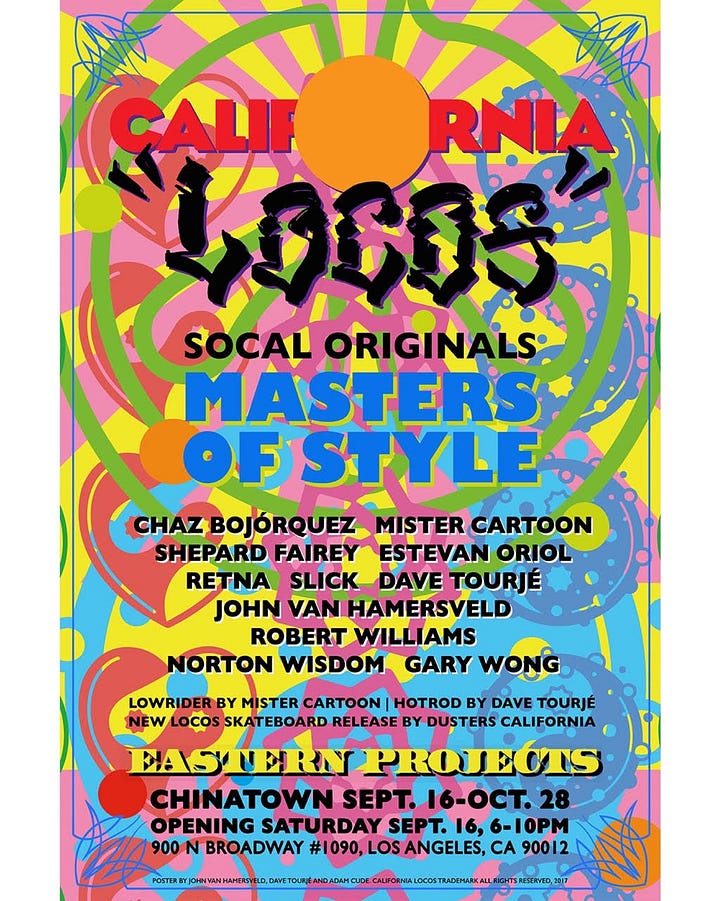

Another communal artistic endeavor began in 2011, with The California Locos, partially an invention of Tourjė’s, formed so that he might collaborate openly under the banner of a name additional to his own; that he could share with a coterie of close friends whose creative chops he admired, and with whom he cohered intellectually and socially. More like a band than an art group, the Locos have to date participated together in a dozen or so large scale group exhibitions that have been expressive of each of their chosen disciplines and passions, and which together and cumulatively, has embodied a grander impression of the image of what it means to be an Angeleno artist than any one of them could have accomplished on their own. Despite what established galleries would have the greater public think, artists don’t exist as lonely figures working only on the sidelines of society. They are in fact members of an inspired and wide-ranging community that speaks, through ethnic and idealistic, between communal and regional expressions, to the larger public beyond borders and also beyond stereotypes. The Locos have become a primary example of what an artistic community can achieve; and through the cumulative force of character of its combined members, they have, thanks to Dave Tourjė , become a band of brothers whose brand is both originality and realness. His partners in this enterprise are each unique and different. John Van Hamersveld is an original 60s pop artist and now a digital graphic designer. He has applied his talents to many sectors of culture like Rock posters, the Surf/Skate world and architecture branding as well as pure art and more; Norton Wisdom worked as a longtime local lifeguard and first responder. This third generation Abstract Expressionist has developed an alternate identity as a pioneering live action painter whose public appearances are in collaboration with renowned musicians at concert events; Chaz Bojórquez is a pioneering graffiti artist whose images have penetrated into the various subcultures such as gang life and other kinds of street culture from tattoo to skateboarding; Gary Wong is one part painterly savant, one part primitive abstractionist, manifesting the subversive connections between spiritual, sports, indigenous cultures and music iconography- one part blues master shouting his soul and strutting his blood, sweat, and tears upon the stage. Along with them, the professorial disruptor who is Dave Tourjė paints his totemic puzzles merging images of mortality and the repressive numbness of the urban sphere into visual celebrations that are inspired by everything from the Finish Fetish to vintage quilting and the sheen of the eternally new culture of contemporary life. The Locos continue to evolve as each member lives and changes their own directions and methods over time, as organic artists do.

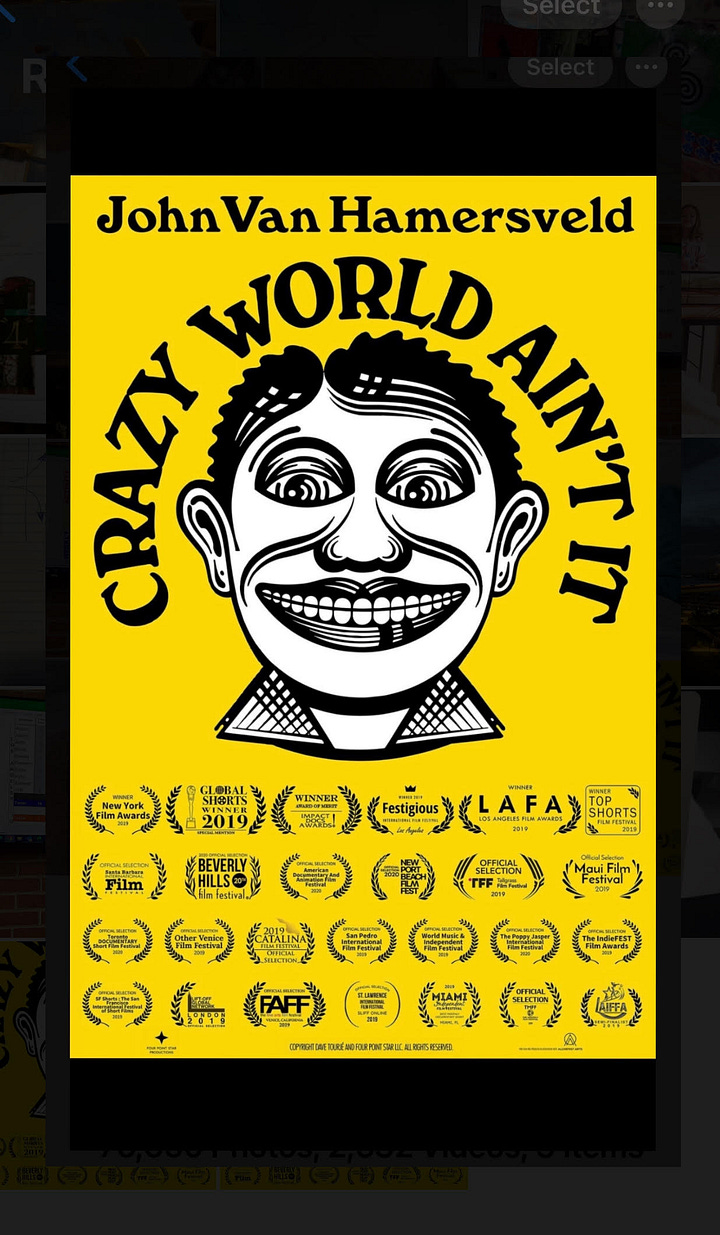

Starting in 2013, Tourjėgot bitten by the film bug, and since then he has produced and directed various award-winning documentaries, more if one includes the various trailers for these films. The stories of the people he knows–his friends, and in some cases, his heroes as well, and the connections they share, the passions that intersect between them: for music, for street culture, for art, and for sharing the identity of the Angeleno. Culminating in the Oscar-reviewed John Van Hamersveld CRAZY WORLD AIN’T IT, about the pop artist and legendary designer John Van Hamersveld; to the recent California Locos Renaissance and Rebellion, each garnering dozens of awards internationally. It seems that heavy chops in art and music allow this “non-filmmaker” to yet make great films. As well, Dream Team Directors Bayou Bennett and Daniel Lir made their own award-winning film about Tourjé himself. Tourjė disrupts the standard art story continuously and on different flows.

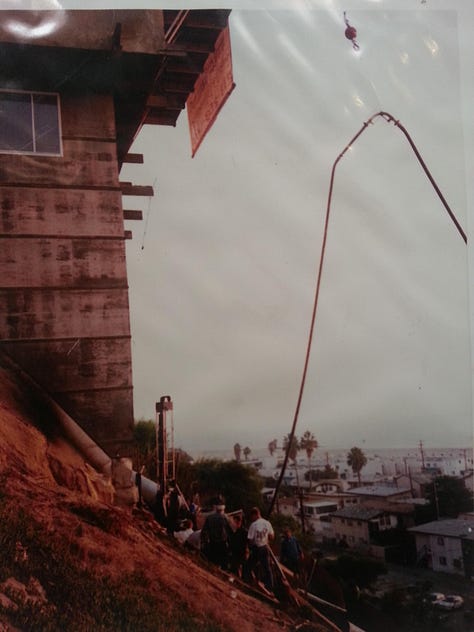

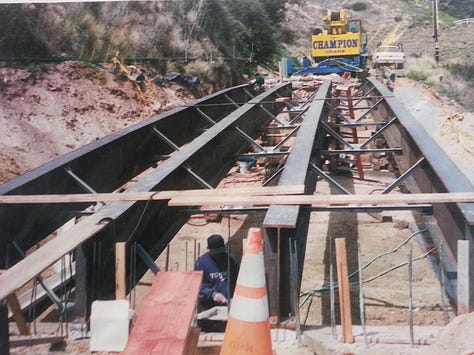

All of these affinities and accomplishments are in themselves important, yet they exist in part because the disruptor is, and has always been, a constructor. The central business concern which has become one of Tourjė ’s greatest accomplishments, and which garnered him his 2023 “Disruptor of the Year” award from The Los Angeles Business Association, is called Alpha Structural, Inc., established in 1993. His award was a surprise but fit Tourjė’s idea of himself. The innovative concept that drove his business is an idea which was always necessary in the Los Angeles area, but it took the mind of Dave Tourjė to originate and develop it into a successful business endeavor. What does any community need, much less one constantly under threat from the random destruction caused by earthquakes, hillside and oceanfront failures? It needs security in the form of reinforcement. The diverse communities that make up the greater Los Angeles area have entrenched themselves upon a plateau that comes with its own essential risks. Alpha Structural not only reinforces the underpinnings of commercial and residential buildings, it also attends to the landscape itself, altering its underground composure so that it will be less apt to give way in the occasion of some natural disaster like an earthquake or landslide. In addition to the myriad of constructive and reconstructive specialties that this company excels in, they have also advanced the overall reputation of the industry by training women equally in positions that before were reserved for men. Yes, this industry was significantly behind in that respect. Yet the foresight Tourjė evinced has altered the business landscape as well.

The lifelong odyssey of the disruptor originates both in his native intelligence, in seeking out creative and professional challenges, and in an unwillingness to lay fallow for any amount of time. It’s important to be cognizant of the polymathic nature of Tourjė’s life and drives. He always did and does several things at once, either a few things over a twenty-four hour schedule when younger, or now, with several activities spinning around in his mind, as he grinds out new forms of expression over periods of days or weeks. A new furniture design, some new songs and time spent with Los Savages, a new painting in the studio, new plans with the California Locos—which may also include poster designs and documentary films—and projects with his architectural reinforcement business, Alpha Structural. It’s been necessary to describe one at a time, but don’t think of each of these disciplines or obsessions as singularly affecting activities. Each one disrupts all the others. Together their disruption forms a rhythm with each subject being an overture, part of a larger, even endless, melody. Dave Tourjė has garnered not one but multiple legacies. His passions are evidence of an ever-accruing passion to make, to collaborate, and to break out of any settled expectation. This is the duty of the disruptor. We follow as avid spectators within the gravity of his shadow.

Great story. Inspiring!