The approximation of value is a human activity on the same par with academic reasoning or artistic endeavor. It’s something that’s been a part of human nature for a long as humanity has existed. The determination of value according to the amassing of numerical facts to match material and chronological circumstances in the contexts of different persons, communities, and societies leads us inexorably into a competitive situation; yet there are also spiritual and aesthetic aspects to this quandary that challenge us to advance ourselves. In order to greet the terms of this challenge on equal terms, it helps to have an object representing quality by which to gauge and express the result. It helps even more if the object is immeasurably complex or idiosyncratic. In the new paintings of Gregory de la Haba we have an exemplary model of objects for reflection. They are both paintings of real objects taken out of an everyday narrative and symbolic embodiments of the transformation of human agency, luck, and fate that movement between places and values can bestow. They offer us beauty and mystery in their mastery of significant form.

De La Haba has a particular fascination with numbers. He finds them along the route he takes each day. They are simple address numbers, often affixed to a doorway in a haphazard fashion, the doorways themselves festooned with graffiti tags that may also include numbers. Larger wall-based graffiti features numbers portrayed dramatically, often referencing a number of person significance. They may refer to a sports figure’s team number, or something less ubiquitous: an auspicious date, one’s age, number of children, and so forth. Personal numbers have an affinity with accidental ones in that, for one reason or another, they can achieve a magical vibration. The numbers that De La Haba locates in his paintings are, by their very association, historically magical, the manner by which they have been promulgated in popular culture attaches them specifically to the activity of gambling. This pastime is symbolically loaded and carries a near cult appeal. The dynamics of chance in determining a degree of luck, and therefore of fortune, is something that we can only surmise has charismatically suggested the necessity for these paintings.

JACKPOT 4 DUENDE depicts a door literally covered with forms and words, a single number ‘4’ affixed at its center above where an eyehole would be. Above the number in carnival style lettering stretching upwards at the ends like two wings, is the word JACKPOT, and below it, in a tagger’s script, is the capitalized word, Duende. Below the word, like sentinels at the door of a castle or temple, are two images of green-glowing harlequins modeled after the artist’s youthful club kid friend Muffinhead. Between them are the words “Fucking LEBOWSKI” in red. The first word we can understand, it means the greatest amount of possible luck, a victory in achieving success in gambling. It could also be stretched to a meaning equal to Eureka, meaning a stroke of success in the discovery of any ardently hoped-for result. ‘Duende’ is little stickier, for it has no exact translation from its original Spanish. The poet Federico Garcia Lorca used it often to infer the feeling of an overpowering emotion, meant as the transmitter of poetic and therefore existential truth, and the power, or spiritual current that put the truth itself into play. To utter the word Duende itself is to speak of spirits and the pure power of inspiration, like the invocation of a prayer. The reference to Lebowski is a filmic one, a character who’s a charismatic loser, an everyman type like Willy Lowman in The Death of a Salesman. He loses but does it with style, and only because he risks everything to win. De La Haba is here crossing boundaries to take his cultural earmarks from visual sources that also possess an archetypal affinity with his own character and aspirations.

LAZY EIGHTS presents a door and the brick walls of the outside of the building over and around it in a greenish cast with a stylish graffiti of mawkish faces gazing at visitors and passers-by. Falling all around and over the faces are many small colored specks, round like glass marbles, though they could be confetti, or gumballs, or technicolor hail. They form a scrim complicating direct perspective. Before them, rising like spirits or electrically charged particles, are three bendy number-eights. They give the impression of being ghostlike, as if the number inferred in each one are a separate person—an eighth child, a member of a sports team, or someone who was born or died at the age or on a day marked by the same number. The three soundings of the same number are like intonations of a wish or a prayer, spoken for effect. Three spirits named 8 rise mysteriously as if through dimensions and are momentarily visible, like flotsam blown in the currents of the wind. They reminded me of the soul of a recently deceased person giving up its mortal weight and rising slowly to heaven. The expression in the title actually refers to an air pilot’s test of appropriate mastery in using the weight and impulse power of the plane to drift through wind currents and rise into a situation of defined control. Luck (or its metaphor, Grace) is often achieved by giving up control and letting the winds, or the wings of angels, carry us.

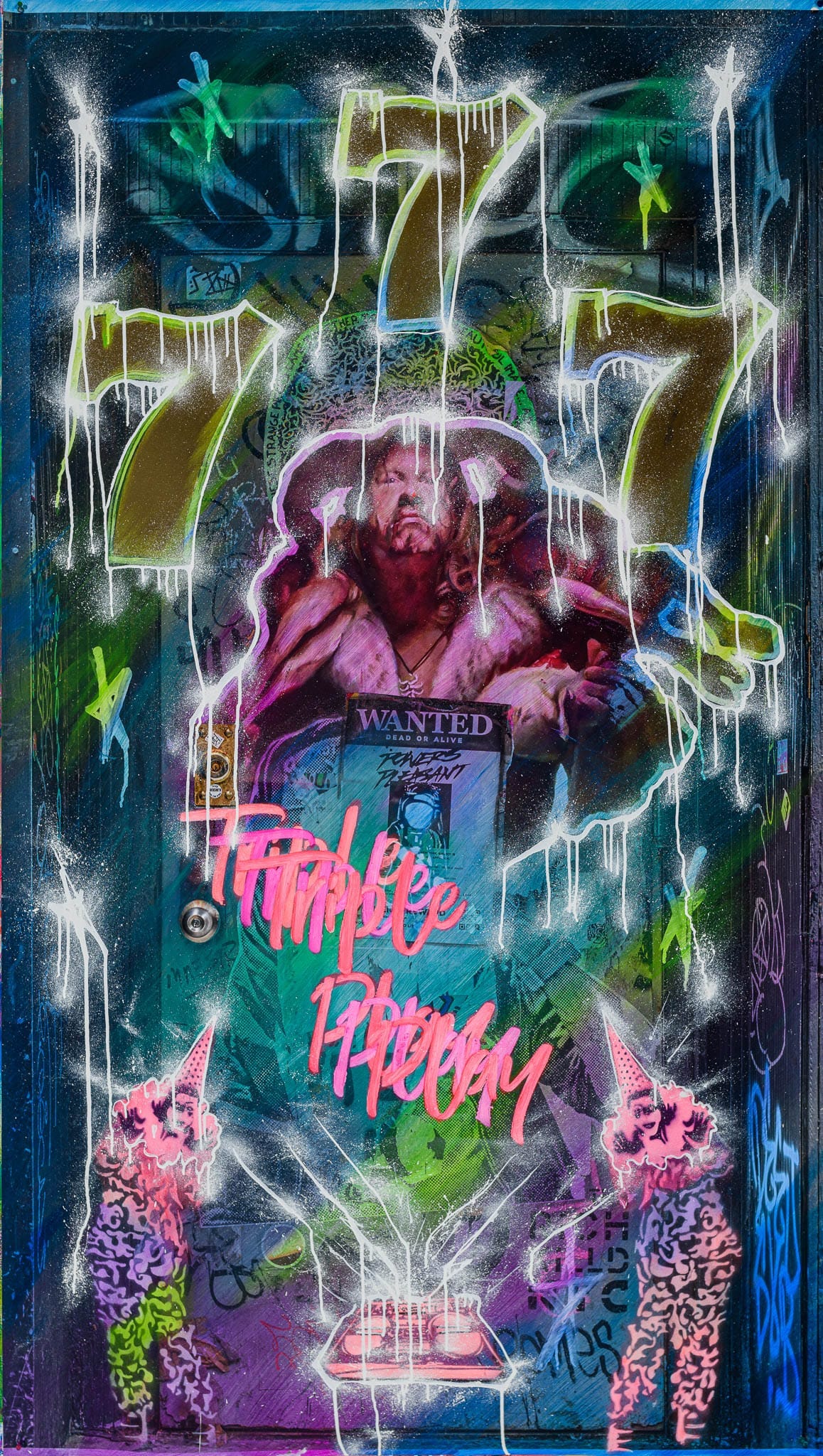

LIFE GIVES SEVENS is another powerful work from the new series. It presents a sequence of interlocking symbols that includes the three numbers of absolute charismatic power, numbers that being prime, and uniquely only divisible by themselves and the Number 1. That’s like saying they are the same number, a further imprimatur of essential importance. To say one is seven is, in the contemporary parlance, the same as being a unicorn or a snowflake. Utterly symbolic and likewise utterly unique. Framed below the three sevens, which in the way they are depicted, seem almost like a halo or a crown upon the image of the artist himself as he appeared in a painting from several years before: primordial man, clothed in the beasts of animals, like a Viking king, his posture solid and resolute, his eyes bearing toward heaven or the future. This early model of humanity is willfulness indomitably possessed, man himself as a force against all nature, and all things yet unknown. Such a man might exist for millennia without grace. Yet to be self-impowered and self-fulfilled is enough. His self-image as existential wildman symbolizes the importance of personal and spiritual growth. Below this image is a Wanted Dead or Alive poster scribbled with the words ‘Powers Pleasant’ and below that the words Triple Play and the trickster-familiar figures of Muffinhead. All around the painting are glyphs of stars painted in spray paint with the starlight oozing like cosmic blood all around the picture, suffusing it with a celestial watermark.

The presence of doors in these paintings cannot be understated. First and foremost, they root the inspired moment in an everyday experience of a city dweller, walking past myriad doorways where some addresses are familiar and many others not at all. The even evolving character by which residents of a neighborhood choose to leave an intrinsic mark upon the bleary normalcy of buildings in working class neighborhoods adds to their aesthetic engagement in the random moment. Numbers combined with doorways became the accrued duende that brought these images brooding into De La Haba’s consciousness. Numbers enter our consciousness with a regularity that is immediately disarming. They count streets and buildings on those streets. Our ability to recall specific addresses and place a value, both personal and universal, on certain numbers, is a measure of our ability to grow as human beings. To belong to a place is to assume the value of the numbers specific to it. Say a certain address according to its number and one immediately knows its distance from the center of the city, from the major thoroughfares, and its proximity to important attractions or utilities in the area. Location, as the saying goes, is everything. De La Haba locates the power of inspiration and places it in portals to new knowledge.

This essay appears courtesy of Art Bodega Magazine © 2022. It was featured in the Fall/Winter 2022 issue as “Divining The Magic Number: The New Paintings of Gregory De La Haba”.