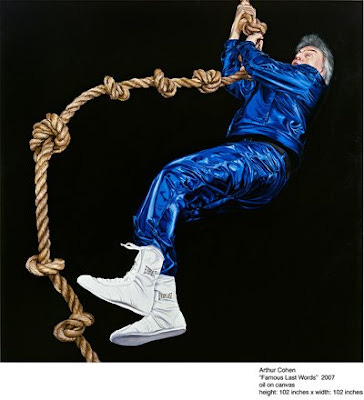

Arthur Cohen at Jack The Pelican Presents

These new paintings by Arthur Cohen deal with the connection between masculine identity, a visual sublime, and their tangent to the ridiculous. Cohen again portrays himself but also another person, a curiously mime-like Korean Buddhist monk named Sunim. Both he and the monk are involved in an activity which has shamed generations of adolescent boys, and which remains, well into middle-age, a symbol of their weakness: the rope climb. Just the thought of such an endeavor can transform the most confident male into a quivering mass of neurosis. The fact that most of us cannot carry our own weight as human beings, except when held against the ground by gravity and the motor urgency of our own limbs and the other processes (air circulating in lungs, blood flowing in veins) is enough to shame anyone, not only on a personal level, but a transcendental one as well. Force us to leave the surface of the earth of our own volition and a million warning signals immediately flash. We’re not meant for this.

In his typical fashion, Cohen loves to skewer himself, but saves a modicum of grace for his alter-ego. Sunim looks completely at home on the rope, as if he were just pausing in the garden with his fan, or taking a leisurely jaunt down the boulevard. It would be sensible to ascribe his comfortability to his role as a Buddhist teacher, following the ideal of giving up possession of one’s body, and all of the problems that go with it. Since we have no body, there is no gravity.

While distracting the viewer with the metaphysical conundrum of a man suspended on the end of a rope, Cohen also charms us with his talent. He has a great love of the human form as swathed in different types of clothes, from bright blue athletic jumpsuits to a patchwork of rags transformed into a monk’s robes. He is conscious that a thin veil of appearances is just another way to reveal states of consciousness, as was similarly achieved by two other painterly fashionistas, Edouard Vuillard and Gustav Klimpt. In everyday life we are taught to revel in overt detail, and to judge people by what they wear, even down to the combination of hues and the stitching of every piece of apparel. In his self-portraits there is evidence of a foolish anti-hero, a harlequin strutting upon the stage of life; and beside him the deft and mute Sunim, a hero for the preposessed, a master of focus, and a symbol of beauty.