By Intimacy Bound

OF COVID: COLLECTIVE TRAUMA [ Kris Graves Projects & Humble Arts Foundation, 2024 ]

The images that comprise this collection are evidence and portent. They combine to illuminate the strands of humanity that have outlasted that fragile interval we now call the Covid Era. Though we’d prefer to sweep our memories of the global pandemic under a rug, it’s necessary to speak for the experiences we’ve shared. Kris Graves Projects presents us with this volume of images that is apt to trigger strong emotional responses.

What strikes me most about the broad spectrum of these images is how they embody the shifting landscape of intimacy itself. When Covid occurred, it completely disrupted a world that was expanding its borders, and in which was in many ways becoming more connected than it had ever been before. At least that was my general impression. There had been great strides in the progress toward easing some of the most major problems of society. Nicholas Kristov, from the Opinion pages of The New York Times, wrote:

If you’re depressed by the state of the world, let me toss out an idea: In the long arc of human history, 2019 has been the best year ever. The bad things that you fret about are true. But it’s also true that since modern humans emerged about 200,000 years ago, 2019 was probably the year in which children were least likely to die, adults were least likely to be illiterate and people were least likely to suffer excruciating and disfiguring diseases. Every single day in recent years, another 325,000 people got their first access to electricity. Each day, more than 200,000 got piped water for the first time. And some 650,000 went online for the first time, every single day. LINK

Then, at the end of 2019, Covid happened. None of us knew or even suspected what was about to unfold. Three months later I had Covid for the first time. I won’t make this article about me, but since it’s about all of us, it’s also about me in some infinitesimal way. I shared in the suffering and its related dilemma in my own way. Looking at the pictures in thus volume, however, does not merely trigger old thoughts. It reminds me how lucky I am to be alive, and that most of my loved ones have been similarly lucky. But the Covid era, or at least its most intense first stage, was about much more than physical suffering. It was about how this suffering altered the very fabric of reality. What remains are the memories, and the ones in these pictures prove palpably memorable. They’re not in any way a documented history, but are each touchstones from a time that was always overwhelming.

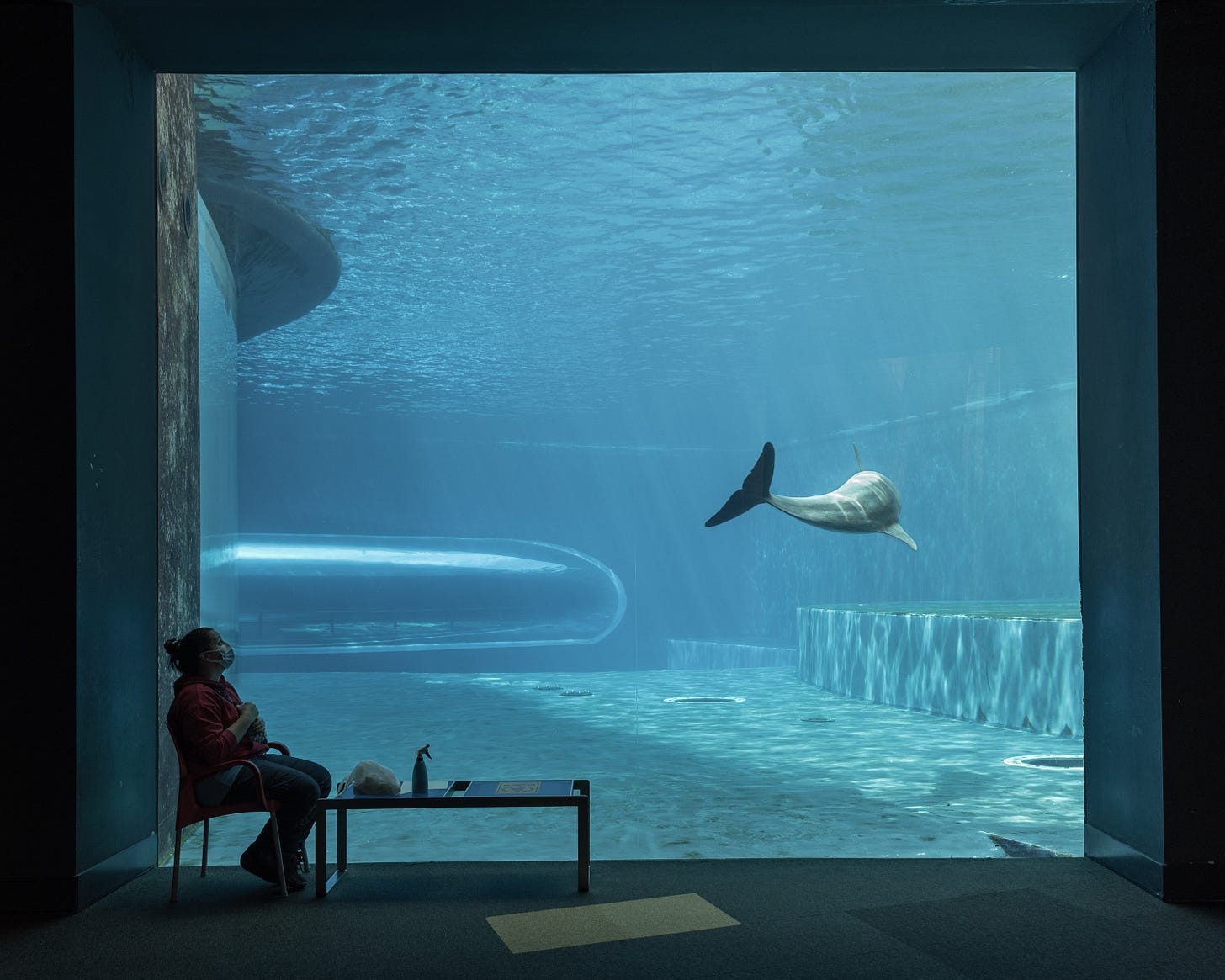

Isolation was one of the repercussions of the social distancing required to maintain safe spaces from the possibility of infection. In the photographs of Annelaura Cattelan we view places that are reserved for public engagement: parks and aquariums, yet in “Since Your Gaze Is Gone” only one person is depicted, a dolphin trainer on her lunch break, sitting in a large empty room, accompanied only by a single dolphin on the other side of the glass. This is one of a series sharing the same name, in which the Cattelan portrays the workers and inhabitants of Natura Viva Park, a popular local attraction in Genoa, Italy. By doing so, Cattelan shows us not only the cultural shifts but the existential awkwardness of life in that time. The only activity that remains is focused reflection and maintaining order through regular habits.

If Covid made us all the more conscious of how we depended upon social interaction, it also affected many people who were already suffering from debilitating afflictions like dementia, in two ways: by further isolating them at a time in their lives when what they really needed was the interaction of caretakers and loved ones, and by exacerbating their conditions by weakening natural barriers that were previously their only respite against future loss of self. Virgil DiBiase’s “1000 Pieces” depicts a short woman of advanced years sitting at a table filled with puzzle pieces. Clearly, the puzzle is an exercise to focus her attention and keep her engaged in a specific activity with a determined purpose. But she’s all alone at the table, and possibly lost in the morass of her own mind. We can’t be sure. It’s sad and oblique at the same time.

As a New Yorker, Chris Facey’s “Holding Back” from his series A Tale of Two Pandemics (2020) cuts close to home. The Covid era was one marked by many issues and agendas other than just the disease. It was also a time of political and social turmoil. It was the era of Black Lives Matter and the era of MeToo movements both reaching their flashpoints. These issues were only complicated by the need to safeguard personal health when protesting racial injustice in the everyday lives of Americans. No matter what dimension our lives took, the symbols of safety–like face masks–had become a part of the history by merely being omnipresent in scenes like this. Strangely enough, the masks in this picture look completely normal. The protestor being arrested and the onlookers, at least some of them, all wear the same mask. It became a signal, like smoke signs, to let people know who was wise and woke, and who was not.

Another image about civil clash and its repercussions is Kilii Yuyan’s “A Fog of Tears” (2020) in which a troop of police in camouflage riot gear with the word Sheriff emblazoned across their chests walks cautiously thorough a haze of tear gas. The metaphor inherent in the image is both filled with portent and is at the same time a single moment in an over-arcing narrative typical to that scenario. It weren’t real, it would be necessary to invent it merely to stipulate the metaphor it represents. The soldiers are walking either away from a conflict or into one. Either with their shields or upon them. Though they are troops representing the force of official authority, they are also human beings who feel.

The role of the mask in the Covid era was fraught with conflict. Many people wore them for self-protection, or if they were sick, to protect others. No one wanted to be responsible for infecting others, although a degree of denial inhabited many shared beliefs about the existential threat that Covid embodied. This would persist unless they themselves became sick. Many supposedly did not. But many had to share semi-public spaces in their residences and in stores where it was nearly impossible to avoid close quarters. Socially and politically determines conflicts ensued. But what most despised about the masks was how they created a lack of choice. Wearing them was psychologically repressive. The photograph “Hide and Reveal” by Asiya Al Sharabi takes this conflict and places a greater weight upon it, one that emerges from the artist’s own culture. In Al Sharabi’ perspective, the basic masks forced upon the general public were a reminder that, in Yemeni society, masks were more commonly used to repress individual identities on several levels.

Intimacy can sometimes be a cage. It’s not the metaphor that usually comes to mind, but it’s true. In the photographs of Asiya Al Shababi, of a series title “Hide and Reveal” we encounter images of masked women whose identity, beyond clothes and hair, is completely obscured by the state-mandated mask she wears. In Al Sharabi’s work the masks of the Covid era bear a family resemblance, and incur a likewise psychosis, to the veils of Yemeni culture. Al Sharabi takes the metaphor one step further by adorning the outer surface of the masks with crudely colored, badly printed passport photographs of years past. The artist finds in the mask a means of expressing the complexities of identity for a people who’ve had to live a life under cover, hiding their true selves from everyday society. In addition, it’s a world in which photography is frowned upon. So neither can women be real outwardly, not can they be seen by others in any documented fashion. In truth, the mask in the Covid era was a double bind: it protected but also restricted, it hid but also marked. It was a statement either way.

For a great many people affected by the enforced shutdowns of Covid, this meant a reduction in the social sphere. For those not given to there merest aspect of a greater social interaction, those who for creative or other reasons found themselves radically alone, the work of Aixao Li will ring true. Her series “I Am With Me” presents an image of two asian women sitting in a bathroom, one clearly naked, the other in just a sheet, wearing a wig she has borrowed from the first woman. They look as if they’ve just been caught in the middle of a very personal conversation. One of them, the one on the right, is the artist, who has organized through social media, this sharing of another’s space, and even of her most intimate accoutrements, which include the wig. It’s an intimate strategy to fulfill personal as well as creative need. We’re caught up in the moment, as are they.

Isolation wasn’t only social, it was emotional as well. For the lives of extended families that formed inter-generational communities, the bonds of affection were severely limited by a risk of possible infection, especially for the elderly. In Mikaela Martin’s “A Covid Kiss” we see two family members having to place a barrier between two lips, and to mime the affection that would normally never be taken for granted. It’s a sad image but a telling one. It shows the undiminished power of love.

Loneliness meets whimsy in the images of Heather Boyd, a Seattle based artist whose series “Wish You Were Here” portray herself in set piece fantasies where she’s always waiting for someone else to arrive. It’s a lonely life that we fill up with childhood memories and projections of a desire for adventure and romance. It tempts us to want to enter the picture and engage with her. The images reminded me of the opening paragraph of Nabokov’s memoir, Speak, Memory (1951) in which he talks about seeing pictures of his parents before he was born. He felt existentially threatened by such images. How could the world exist for them in which he was not included, in which he did not complete their happy union. This is the same dread that infuses Boyd’s work no matter how whimsical they seem. The empty chair in each picture is a portent for the future. Will it be filled? She makes us want to join her.

Another aspect of how the Covid era affected everyday life was that all the main communal experiences that define living were either severely circumscribed or completely transformed. Major sporting events were one such example. In Kevin Reeece’s “No Real Fans of the Game” we have a picture of the stands at Dodgers Stadium completely filled with highly realistic images of sports fans on cardboard silhouettes filling every seat in the stadium, with the only real person is a professional photographer, there to document the game for newspapers and tv sports news shows. He uses large zoom lenses to get as close to the action as possible, but like the veritable tree falling in the forest, there’s no one there to see him seeing the game for us.

Forced isolation was not by any means the worst condition suffered by many during the Covid Era. Somewhere in the world, people were dying. We saw the news stories. We heard the statistics. It was unimaginably horrific. The whole situation placed me in a state of emotional stasis. All I wanted to do was sit in my armchair and not think about anything or even breathe until it was all over. That was the kind of fear it instilled. Yet one has to get up every day and do the same things, no matter what’s happening in the world. Every day I had to walk my dog, morning and evening. It didn’t matter that my neighbors were self-entitled Covid deniers who stepped into the elevator without a mask and just didn’t look my way. It didn’t matter that sometimes my walks coincided with the daily yelling and bashing of pans from windows and fire escapes up and down my street. It didn’t matter that my eerily quiet neighborhood might also be transformed by parades of the demanding and the desperate, marching down Second Avenue from Gracie Mansion. None of these things mattered because somewhere, people were suffering and dying. But for myself, and I’m sure for many others, it was the share of suffering we could afford to give. It was important to survive all of this. Not putting myself in harm’s way was one way to ensure my survival, so that I could continue to be there for my loved ones. Many of the artists in this book did exactly the same. They stayed home, and they found ways to make the best use of their time. What Kris Graves Projects delivers with “On Covid: Collective Trauma” is more than a portrait of our time. It’s also a fantastic collection of vibrant stories told by talented artists, many of whom are new to me. On Covid stands as testament, but its brilliance and its honesty also predicts the quality of stories left to tell.

David a great piece of writing and reflection. Each chosen photo illustration

Were also so poetic. Wonderful

Nicely done, David. And some really good photographs. The couple kissing through the barrier: I'm pretty sure that's the top of a container for a store bought cake. Which adds something. More generally, I think covid in NYC was particularly horrific. The City is claustral enough when all is working well . . . anyway, good work.