The human form is possessed of such redolence that it never fails to deliver a degree of the symbolic. In the paintings and etchings of Eric Sanders, we peer into the world of art, and we see the gears moving as he reinvents the wheel of artistic affinity, creating formal experiences that possess a renewed resonance for our time. The symbols that inhabit great figurative oeuvres of the past, no matter which epoch or movement first generated them, contain a reflective content that finds new life in its reconsideration by artists of the present. One of the most productive agendas that an artist can have is in the act of interrogating archetypes, burrowing down into the aesthetic subconscious to re-establish the primacy of the intrinsic experience by which art influences who we are as people. By establishing a creative continuum between the images and methods of the past, which though highly recognized each for its merits, as well as for the extensive impression one receives from a repeated confrontation with such works.

Sanders presents a broad expanse of creative vision extrapolating historical affinities that complement his mastery of multiple formal disciplines. The prospect of this exhibition opens up his production to a new range for variables, for which specific formal aims seem tailor made. In particular, two ways in which Sanders can respond to the articulated legacies of artists such as Eadward Muybridge and Gerhard Richter, vastly different intelligences who share a discernible aptitude for significant form. Sanders translates their achievements into a fresh new experience for contemporary viewers.

In Sanders’s “Nude Descending Staircase” series, we have the same image interpreted three different ways. In the first image we have his wife and central muse, Anna, slowly descending a staircase with not a stitch of clothing on. This image arrested by paint is both beautiful and mysterious, for there is a narrative to which it belongs which remains unstated. In versions 2 and three of the series, Anna is transformed by alternate technical processes, which renegotiate the emotional space of her portrayal as radically ethereal and symbolically transgressive, turning from an angel into a devil. She starts out as a beloved figure sheepishly walking to greet him with sleep still in her eyes, perhaps as part of a daily ritual, or for a surprise. But in each later version the view we have of her is first obscured by layers of thrown paint, and successively, by a darkening of the area around her visage, so that affection looks more like anger. Sanders shows us all the layers of possible emotional delivery in a given moment, while at the same time communicating to other historical versions by Richter, Duchamp, and Boccioni, who all played with how the body could be transformed in the immediate moment of confrontation.

Sanders’s two-part monumental work Star Walkin’, relies upon large scale images of the artist’s wife as a figure whose poise and grace are aptly put on display not only to celebrate her as a muse, but to talk about the poetry of movement, and the universal condition underlying all depictions of the human. What does the artist receive from his muse? Sanders gives us evidence of his high regard, presenting Anna as powerful and impassive. The same characteristics that imply universality also describe idiosyncratic dimensions. Her figure though, is no empty cipher, but a person, and filled with self-possession. Add to the mixture a degree of intimacy and it becomes impossible to merely witness the possibly ethereal formal qualities that activate it as a symbol. The formal elements that dominate in each version are less stylistic and more akin to tropes, structural and elemental differences that dictate specific aesthetic consequences. In one part, Anna walks, or rather her many selves walk in a long line, marking esthetically charged space and narrative time simultaneously. There is a transience in her figural singularity, and the white space surrounding her magnifies every minute detail on her face or body that accents its difference from the commonplace. She is Anna, but she is also Eve, or Lilith, or Ariel. She is every woman inhabiting space and defining it by a persistence of idiosyncratic presence. In the second part of Star Walkin, we have Anna again, but in this case her eternal tread is interrupted by a long gesture of green splashed paint. This one element alters the essential narrative. Consider it not as a naturalistic occurrence, but as thematic interruption and dynamic conflict. What the colorful gesture implies is more important than what it does.

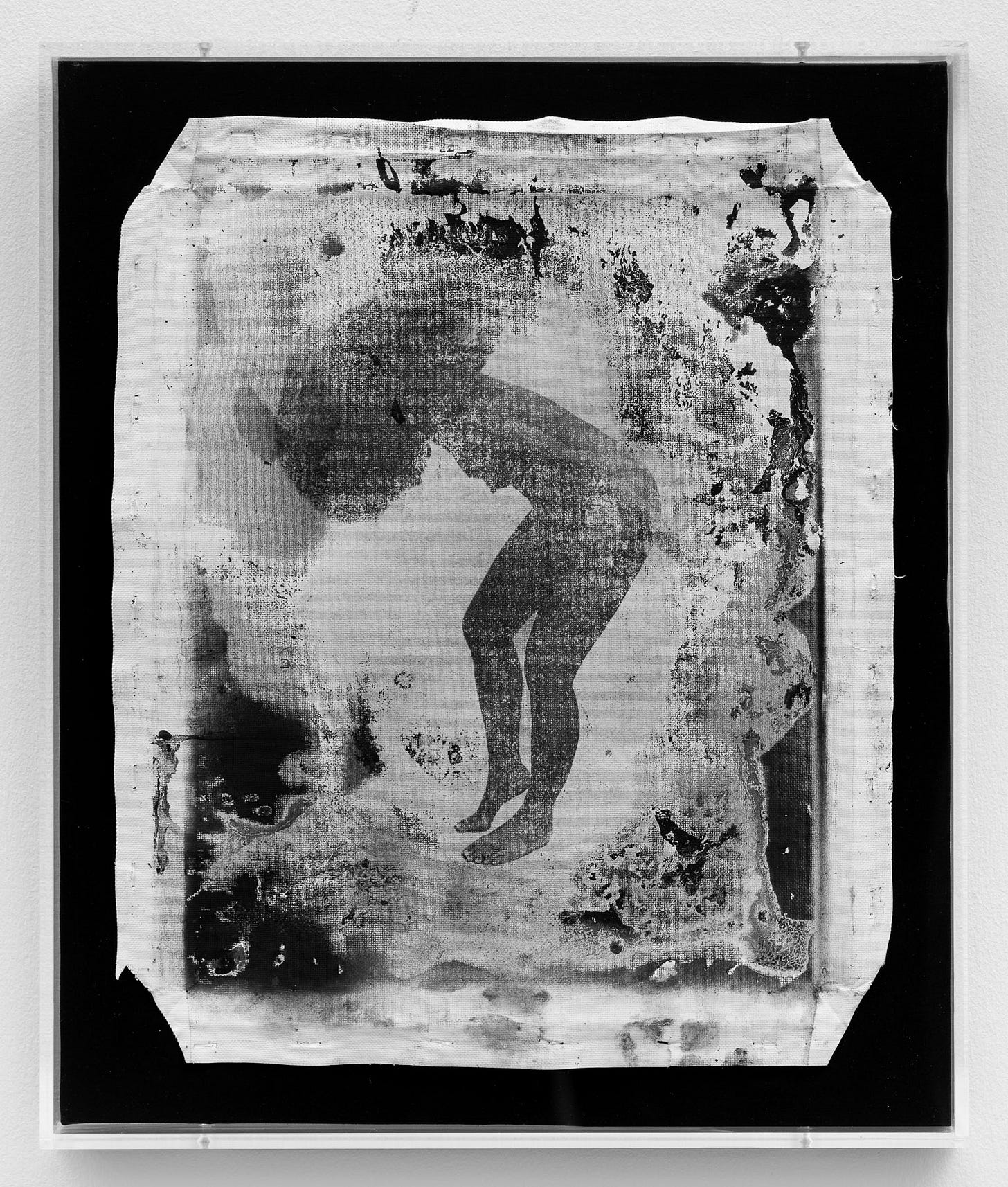

Another series by Sanders is colored by a consistent theme aided and constructed by use of specific technical constraints combined with an intimacy-inducing scale. The Lithograph Transfer series, for want of a better name, depicts Anna as a less definite presence viewed in smaller and less discrete terms, as if from a distance or through a scrim, creating intense physical impressions that are alienated from the viewer. Her figure becomes something skin to a second-generation reflection, like a shadow projected upon transparent surfaces as it passes beside an incongruous light source, as in an early form of photography utilizing glass plates, called a daguerreotype. The figure projected is, as in other cases, also naked, though here her gestures come off as highly eroticized, owing to the details of body features while facial expression and pose are reduced to a silhouette. Here she is in All Comes Crashing--bent over, flinging her long thick hair, as if in laughter or pain, and here she is in Bang! -- silent and still, lost deep in thought. What’s really happening in each of these images is only a guess on the part of the viewer, while intimations of a sustained eroticism persist in memory.

This dynamic and diverse group of series presents a moment orchestrated by Eric Sanders in which the viewer enters a relationship with the artist’s muse, which though it may seem to be contained and projected via a specific person of great importance to him, is in reality a particularized element—the muse as canvas, or the muse as method. The active symbol which Sanders confronts is an epochally derived archetype that inhabits the form of Anna, his wife, who becomes every dimension of woman, and of human, while directing the dynamic of painted and graven images, enlarging their presence and deepening their degree of portent. Eric Sanders is the maker, but he is also the collaborator, or as a famous iconoclastic writer once claimed, he is the antenna, receiving and transmitting a fuller sense of meaning into a shared future.