This article is part of my Portrait section which is a limited series of articles on a single individual, combining an exploration of their creative pursuits with other interests and lifetime events. The first series, four articles long, tells the story of Nolan Preece, an experimental photographer living in the American Southwest.

It’s no simple task to tell the story of a life. One can easily recount a stream of minute details. Yet a creative life is made up of different aspects that don’t all fit into a simple narrative. Life itself goes in myriad directions at once, and on the surface the art-making may seem the more obscure and inscrutable dimension. Yet it’s the one constant that stands as the signifying bulwark against all other concerns, no matter how such other matters as paid professional labor, institutional and communal support and education in the arts, and the pleasures and duties of married life, bring a richness to life itself.

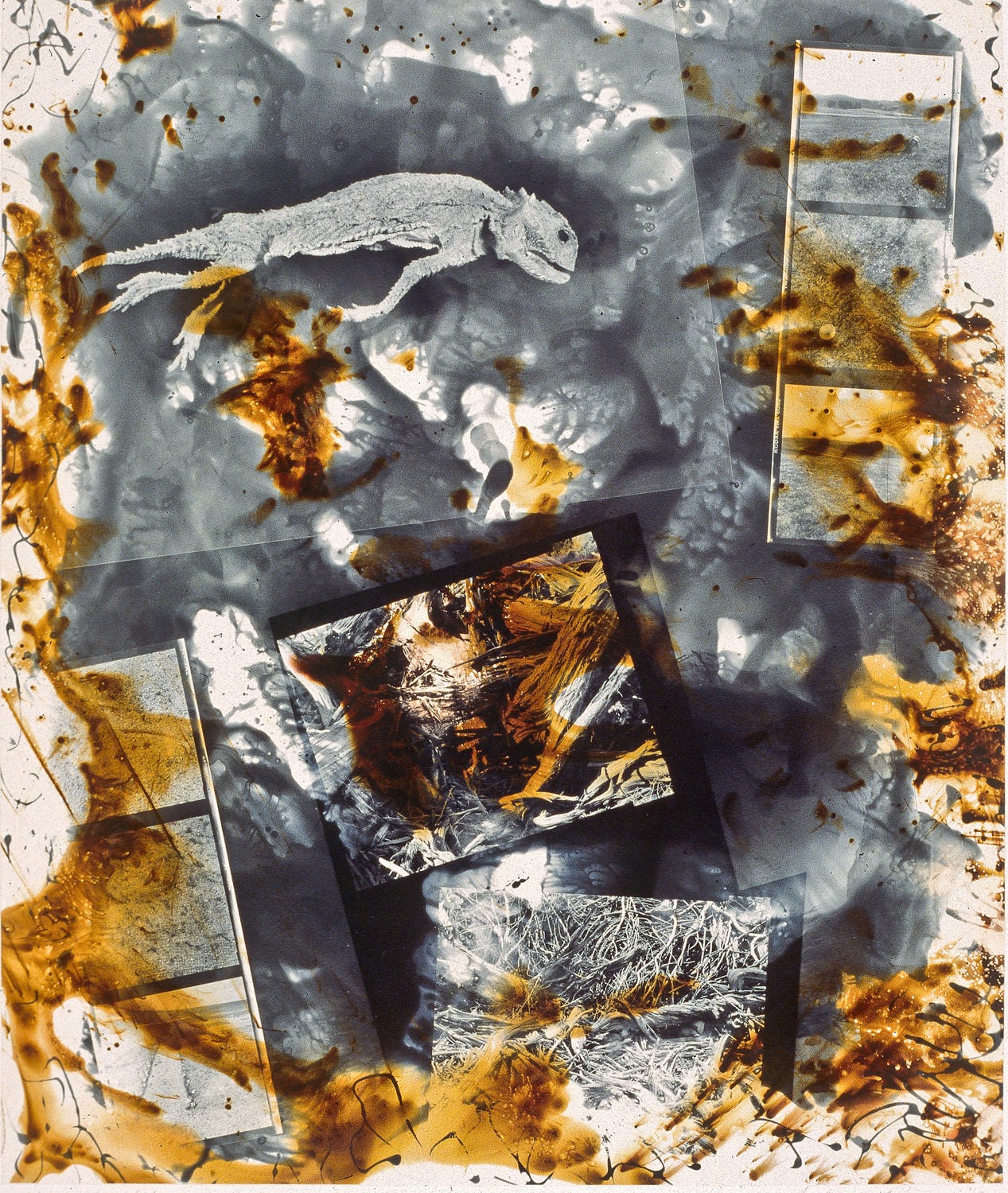

As we re-enter his story, Nolan Preece has completed his Master’s Degree in Fine Arts/Photography, for which he has labored on for six months, during which time he re-engineered the historically obscure discipline of the Cliche-Verre photograph—to which he has brought a quality of inventiveness couched in ideas of form, and technical virtuosity that did not exist in the mid-19th century. The forms that occur in Preece’s Cliche-Verses are similar to organic lifeforms at the molecular level. They have a fluid quality that infers a figural elasticity. In certain instances, Preece has given them what resemble eyes, so that their depiction allows for a sense of agency and a pictorial drama. Any form that resembles a body takes on some degree of relation to humanness, and by extension, allows the viewer to project emotions and narrativity upon a given scene. Preece’s works all have a double life that is reflected in their titles: a word or expression which describes some central formal dynamic or object within the image; and its compositional makeup—the chemical elements that determine its distinct character, beyond the forms expressly present. They share this combined existence with songs, which are named by titles, but defined by the notes which only a technically comprehensive understanding will reveal. The suggestible forms to which Preece gives his titles appear alternatively moody, pathetic, and comical. They instill a range of expressive form accented by chemically generated colors. Others are evoked in tones of palpably turgid black and gray in counterpoint to lines of white and silver, like creatures emerging from obscure depths or images viewed in an old black and white film. They do not merely sit within their apertures, but glow forth, and when seeming to describe personae, they gaze into our eyes. The chemicals are being made to speak with us. It’s this dynamic that characterizes all of Preece’s work, an inner depth bespeaking a raw take on reality, and the appeal of Preece’s virtuous achievement sets him apart from his historical forebears.

Following his Cliche-Verre works, Preece begins a new process which he calls “Chemigrams”. The earliest successful version of this will emerge in 1981, and his production of them will become the signature format of his ongoing creative life. To date he’s been making them for fifty-three years, and he has perfected them into several unique series. Preece’s developments of form and expressiveness within the “Chemigram” have had three distinct periods, each one characterized by advances in both process and concept that differ vastly from what came before. The first dates between 1981, shortly after Preece achieved his Masters in Fine Arts degree from Utah State University, and 2005. A self-determined drive toward experimentation was the original impetus, Preece having already established his ability in traditional modes early on in his education. Considering the usual periods of artistic conception, allowing for distraction and fallow periods of creative inaction while the imaginative muscle rests and re-energizes, or as Preece likes to call it, “achieving the intuitive balance between process and concept,” an arc of twenty five years is long by and standard. The works in this series are best described as formally aggressive. They contain all sorts of events associated with calamities or crises. Preece explains the reason why he made his initial series of chemigrams in this fashion. Preece ascribes this aesthetic as a by-product of religious baggage from his youth, specifically Mormonism. But he also held a belief that every image he produced, since they were costly to begin with, it “had to be entertaining to an audience. Just as an actor has to hold the attention of many people, a photograph should be able to hold the attention of a viewer for at least 30 seconds. I have pretty much held to that view however my motives have changed, such as being an activist for the environment or searching for a whole new process that I can call my own. I consider myself as much an inventor as a creator, however this does not matter much if the subject is uninteresting.”

Despite the imposed drama of these images, their titles are the reverse, they are analytical and scientific, describing how the dual chemical (perhaps alchemical) elements in each (Gold and Silver) are interacting with one another: “Ag Encounters Au” (1983) or “Au Descends on Ag” (1988). These descriptions give the viewer an even more mysterious and exciting perspective. One is viewing forcefully new and experimental forms of photography that exercise the idea that chemistry can be made to serve painting, and that an intuitive as well as a formulaic approach to the methodology of standard photographic processing may result in exciting new aesthetic encounters. The other is that mere theory can be replaced with or counterintuitively motivated by the interjection of themes or agendas that serve humanistic concerns beyond art itself. Ecological and environmental matters have taken on a strong and consistent presence in Preece’s work. They were especially prevalent in his first two series of Chemigrams in different ways. They took on a different texture and context in the third series, which did not begin until 2012 and ended last year. These images were the product of a much more advanced sensibility.

Preece’s middle years see him continuing to utilize his authority and technical skill as a photographer for work purposes. His photographic talents are being put to good use in a series of jobs for Bio West Inc and Bio Resources Inc, two companies where he had friends who recognized his talent and his devotion to work related to ecology and the land. They hired him to help complete government Environmental Impact Statements, the first in a joint project with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the second being with the White River Shale Oil Corporation of Phillips, Sohio and Sunoco oil companies to mine oil shale in Eastern Utah. In 1980, Bio West hired Preece to help conduct instream flow (depth) and velocity measurements along a length of the San Juan River. He and members of the crew would stretch a cable across the river and measure water at intervals marked on the cable with a flow and velocity measuring rod. These measurements were made to establish how much water was being released and used from the Navajo Dam and just how healthy the river was by taking invertebrate samples along the way. That same year the crew was moved to the Northern Cascades to conduct flow and velocity measurements on several rivers for the BIA and the salmon issues.

Bio West also hired Preece to help shock fish for counting and recording endangered species, in cooperation with The National Park Service. Starting in 1980 and continuing until 1984, Bio Resources Inc hired Preece to help with Environmental Impact Statements for the White River Shale Oil Project, which was undertaken to understand what it would take to mitigate wildlife populations back to acceptable levels following the mining of oil shale reserves. This type of field work appealed to Preece very highly, as it brought his critical and logistical aptitudes together for an extremely positive outcome. This was work vastly alien to his artwork but of which he could remain proud.

Around 1983, the oil shale industry was falling out of favor due to the election of President Reagan. Nolan decided that “The environment is going down, and missiles are going up so I guess I will go to work at the rocket factory.” Preece had friends already working for Morton Thiokol in their photo department. They were located out in the West Desert of Utah, a 45-mile commute from where he was living in Logan, UT. On his second interview Preece was hired as a Photo Tech A. It was the beginning of 1984. What he learned while working for Thiokol was essential to his practices as a photographer, and these lessons bled over into his teaching disciplines later in his professional career. The photographic documentation of various types of industry in the workplace gave Preece the knowledge of how to portray his subjects while at the same time requiring him to develop a discretionary attention to detail. The first two years that he worked for Thiokol he was just developing film that had been taken by others, according to Preece this amounted to some 40,000 prints. The third year he was in the field taking eight reels of film each day. This work was strictly in the darkroom, and though Preece had access to a variety of expensive equipment like Hasselblad, Sinar, Nikon and Horseman cameras, the process of endless development was killing his love of the medium. The third year he became a “shooter” taking eight rolls of film each day. Following the Challenger Space Shuttle accident in January,1986, a general malaise set in at the workplace, and Preece decided it was time for him to call it quits in 1987. Although he was given a NASA Award of Appreciation for his dedication to the critical tasks performed in support of returning the Space Shuttle to flight status.

Like many artists with established professional credentials, Preece was now prepared to enter a career as a teacher. This began in 1987 when his major professor at Utah State whom he had studied photography under, named Ralph Clark, went on sabbatical. Preece took over his full schedule of photography classes through 1988. During that time, Preece heard of a tenure track position at Casper College in Wyoming. He went for the interview and got the job. They asked him to set up a new photography and printmaking department. Moishe Smith, a Guggenheim Fellow, who had taught Preece printmaking was also important to his hiring, so the serendipity of the opportunity was even more special.

However, the great moments in life don’t always wait for perfect timing. They occur on their own fated timeline. Just when Preece had gained this wonderful position in a surprisingly advanced department, he met his wife to be, Jeanne Chambers. She was a Doctor of Natural Resources, having just received her PhD, and was working for U.S. Forest Service Research in a special program that allowed for her to be enrolled at U.S.U. while finishing her degree which would grant her the position of Scientist. They had met through mutual friends working in the environment, and he went with her to her research sites during summer breaks to help collect data and document them photographically.

He and Jeanne had to settle down, of course, and a decision was made that he would leave his teaching position at Casper College. It was a regretful leave-taking, but necessary. Jeanne had to follow where jobs related to her field became available. They regrouped in Logan, Utah, while she requested an assignment to a different location. They picked Reno and the Rocky Mountain Research Station. They bought a house in Reno in 1992, and Preece started the remodel while Jeanne went to her job. Her background in scientific research related to the U.S. Forest Service was not only compelling work, but it provided an anchor between them, for they shared work interests in areas that related to the environment and ecology, essentially reinforcing their relationship to the region in which they lived. Jeanne was studying the effects of invasive species such as Cheatgrass, that spread into ecosystems and provides a tremendous fuel load for wildfires; it then displaces native plants such as Sagebrush which is an umbrella for many species including Sage Grouse. She was establishing a baseline for gauging the proliferation and soil seed reserves of the invasive plant versus the native species by use of prescribed burns and testing the viability of regional ecosystems. It was a great boon for Preece to be able to share this engagement with her, and to bring to her studies his own background in field work associated with environmental impact research. He traveled along with her in the summers and collaborated with her on a volunteer basis. Over two decades working with scientists in the field had instilled in him deeper insights into the degradation of the environment and they offered him suggestions about how to capture these insights photographically.

It took six months for Preece to remodel their new home, but he wasn’t just doing carpentry and painting. He was doing his photography, and some printmaking also, whenever he had the chance. He took advantage of any makeshift darkrooms, or ones that were provided by others for his use. He was beginning to enter national juried exhibitions, winning awards and getting into collections. This was with his new chemograms, which were an unexpected hit. He was doing camerawork while traveling but also thinking about environmental projects. It all evolved together. He never felt he had enough of a body of work on hand to feed all these endeavors, and was continuously driven to add to his oeuvre.

As if all of these things weren’t enough, to keep him busy, Preece also desired activities that would moor him within the local art community. Since he was no longer teaching, he needed something. He ended up with several endeavors and affiliations some of which continue to the present day. The first of these was his opening a local art gallery called Sun Mountain Artworks. A fellow artist and friend owned an art gallery/frame shop in Virginia City and in 1995 that he had previously decided to sell. Preece bought it. It had a frame shop attached to it which provided income to maintain the property. Sun Mountain Artworks would be Preece's “second home” for the next 6 years. It had space in the back for a darkroom and a printmaking facility. Preece inaugurated the gallery by hosting a show of prison inmates' work that was produced at the prison in a class taught by a female artist. There was also poetry being taught there as well. We teamed up and put a show together with a poetry reading during the opening reception. The whole event was videotaped so the inmates could see its effect. This was the first of fifty-three exhibitions he presented, on a monthly basis, over a period of five years. Preece upgraded his framing skills and learned how galleries operate. Sun Mountain Artworks became a local hub for the art community, and brought new opportunities, including an invitation to become the director of the Comstock Arts Council, which was a salaried position of some importance. He was similarly approached to teach printmaking the following summer at St. Mary’s Art Center in Virginia City. Preece had in fact just purchased a new etching press. Here was an opportunity to re-enter the world of teaching, which he had missed. It also provided another alternate revenue stream. This was the beginning of seven years of teaching photography and printmaking summer workshops in Virginia City at St. Mary’s Art Center. The Center was not owned by the church but by the county and was a historic site. It had been St. Mary Louise Hospital during the boom days of the mining town and had been given to the county in the early 1900’s. It had four stories and a large studio space. I was asked to sit on the board of trustees in 1996, and has been on the board ever since.

It’s been sixteen years since Preece completed his graduate degree, and life has taken on an altogether different shape than he could have previously imagined. He’s well along into a new version of himself. But this is only the middle of life that’s been spent making adventurous art, working to improve the regional environment, teaching photography and printmaking, getting married and setting up a forever home, opening a gallery, joining arts organizations, and all along, making, always making art. The Journeyman is called this because he’s on a journey, he constantly seeks the horizon. Chapter Three will address Nolan Preece’s creative mastery and the still unglimpsed challenges that lay ahead.

Notes:

Brockway, DG; Gatewood, RG; Paris, RB (2002). "Restoring fire as an ecological process in shortgrass prairie ecosystems: initial effects of prescribed burning during the dormant and growing seasons". Journal of Environmental Management. 65 (2): 135–152. doi:10.1006/jema.2002.0540. PMID 12197076. S2CID 15695486

Excellent !!! your writing gets better and better!