Labyrinth of Nostalgia

The Art of Anna Novakov

Nostalgia is an idea, but it’s also a powerful tool, like a well-made paintbrush. Anna Novakov, in her upcoming survey Yugotopia at Viridian Artists in New York, uses nostalgia in diverse ways, recalling childhood games, staring out over the vistas of Belgrade, and considering newsworthy events of the day as personally and culturally relevant. These and other contexts form a labyrinth of encounter that engages both with who Novakov once was—having evolved through these experiences—and with who she’s now become, having transformed their meaning into art. Several bodies of work comprise this exhibition, yet a cumulative appraisal of her final archive of ideas somewhat undermines its effectiveness. The three most telling works are Hide and Seek, various hand needlework pieces, and Admiring Glances. Each one gives us a unique perspective on Novakov’s identity, looking back on experiences that have informed her creative history.

Hide and Seek (2024) begins with a childhood act indelibly portrayed in a photograph. Anna, as a child, is playing a game with her father. She takes the instruction to hide and, holding her ground, puts up two fingers, each covering one of her eyes, as if to obscure her sight (or, as the saying goes, the windows to the soul). She is willfully obscured and thus, hidden. Despite the seeming silliness of the act, it speaks to a certain idea about what constitutes reality and how one exists within it. A child is weaker and more vulnerable than her adult counterparts. A child has not yet developed intellectualized concepts of what constitutes either individual or social identity, and other aspects of social construction necessarily follow—such as the idea of safety. A child may understand that the presence of a parent confers protection, therefore minimal hiding is required. Or consider that to hide oneself is possibly to become lost. A child of a certain age has social aspirations that hinge upon a desire to be seen, to assert their presence, just like any adult. Therefore, hiding—which is willful self-obscurement—represents a psychological regression that is to be avoided at all costs. A third possibility is that the gesture of placing two fingers in front of one’s face is a symbolic act with some ritual quality, akin to gestures that a shaman might make to enact a spell of protection. Despite the innocence of the subject, she may still realize some aspect of what this gesture can mean. Novakov transforms the gesture, and the image of her former self, into a design for a camouflage outfit—a hazmat suit filled with and embodying this charming yet loaded image. The suit then becomes a further tool for her to be portrayed wearing in photographs, lying down in a natural setting surrounded by fallen autumn leaves. These leaves match the tonal complexity of the gridded photographic images upon her outfit, obscuring her and placing her back into an unremarked and contiguous natural world. She is hidden within her innocence.

The hand needlework pieces present various scenes from everyday life in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia (then, Yugoslavia), in idealized images that depict street scenes and vistas sourced by the artist from an archive of images from the 1960s at the Belgrade City Museum. These images, which are both extremely banal yet striking, are examples of individual observation that typify the kind of commonplace engagement that naturally becomes, over time, fodder for nostalgia. In Striped Shirt, a young person wearing a red-and-white striped shirt stares out over the city from the room of their apartment building. This image recalls the roving perspective in the first third of Wim Wenders’ film Wings of Desire, in which the angels silently travel around the city, over great areas and into individual lives, hearing their stories and offering them comfort. The figure in this image seems young. Much of young life is aspirational, meaning one spends much time dreaming of a possible future and projecting one’s mental state into the world. Any vista becomes a space into which one can imagine doing something new, being someone new. Any image can serve as the basis for an action or narrative, into which any story can be placed. Consider Red Boat or Blue Car as parts of a chase scene in a James Bond film. The images are instantly transformed from generic into universal. This is the nature of experience—it speaks not only to what’s past but to what can possibly be. Soren Kierkegaard once famously said, “The most painful state of being is remembering the future, particularly the one you’ll never have.” Or another quote by the novelist Isak Dinesen: “We invent the past and remember the future.” Both quotes speak to the nature of human experience and its connection to identity. We are who we want to become, despite being exactly who we’ve now become. It’s nearly impossible to differentiate between the versions of ourselves that have all merged into one. We can look back and sometimes recognize a person we used to be, someone who hadn’t yet learned all the lessons that brought us to the present. The artist is perhaps most apt to create a future for themselves, because they can manipulate their memories to mean more and different things than previously imagined.

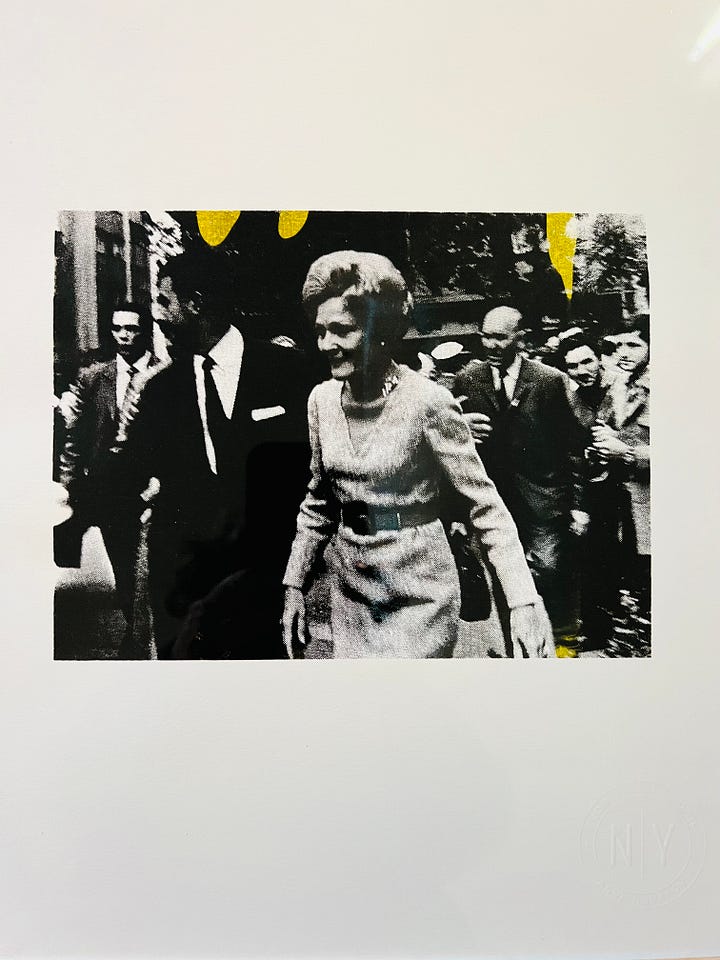

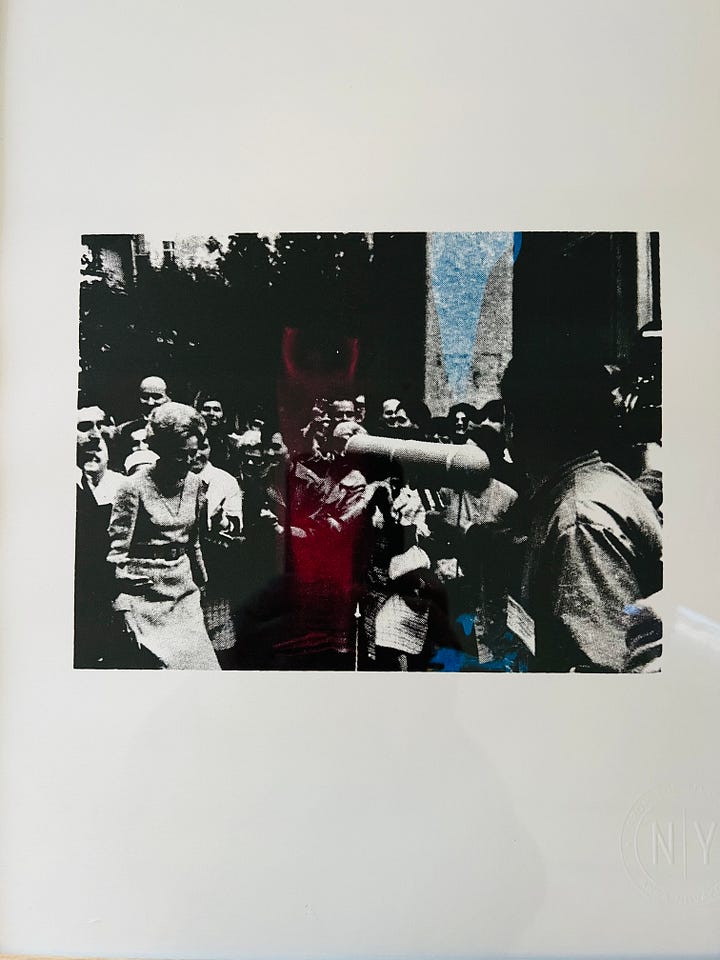

This brings us to the third series of distinction within Yugotopia, titled Admiring Glances (2023), a series of five silkscreen monotypes based on a specific event in world history and a Tolstoyan "News of the Day" mentality. This work contextualizes President Richard Nixon’s important visit to the then-fledgling Yugoslavia, where he traveled with his wife, Pat Nixon. They spent the entire visit in the company of President Josip Broz Tito and his wife, Jovanka Broz. Novakov describes the visit with images taken by the press, which were highly publicized interactions between the wives—both present as official companions, as marital partners with no political responsibilities. According to Novakov, the original press photos published in Yugoslav newspapers focused on the “admiring glances” exchanged between the women. This dynamic adds a layer of idiosyncratic meaning to the events, revealing more about cultures meeting and an unspoken connection between the two unofficial representatives. It puts the temporary dynamic in a human context open to greater interpretation.

Art, no matter its procedures and strategies, is always about what it means to be human. The art of Anna Novakov plumbs the depths of identity from various directions. We see her as a child, playing a game with symbolic dimensions so culturally defined that the single photographic image taken of her in this interval has generated a work of art. There’s nostalgia at work here in cooperation with a refined concept of what “hide and seek” can mean. It’s about the search for identity within very limited rules. Again, we are made to recall the same vista suggestive of imaginary narratives that Novak finds in a historical archive of historically generic photographs; observing them we become the same sort of observer she once was. Lastly, she takes us back to a specific moment in the history of world affairs, a poignant series of interactions between the wives of world leaders, and the alternating models of womanhood they present to the world as they trade silent glances. History inhabits all of these sets of images, and the narratives styled through a complex and ambiguous nostalgia seen in these and other works on display.