The idea of beauty is everywhere in the paintings of Frank Lind. As an artist, he holds both an intense regard for the iconic images that persist in the paintings of artists like Johannes Vermeer, Winslow Homer, and John Singer Sargent to name just a few. These images are etched into the history of art, and they are likewise parables taken from contexts beyond art–stories borrowed from history and myth, and with the advent of Romanticism, images emerging from the real texture of everyday life. Lind has allowed such images to permeate his imagination while at the same time recognizing that they might be improved through a metier of aesthetic interrogation. His means of accomplishing this is to weaponize the Nude.

Much of what is considered important in the achievements of such recognized figures as the ones named above relies heavily upon certain social and political aspects rather than beauty alone. It began to collude with modes of cultural authority–to be made esthetically separate. Yet beauty in a certain form has always been separate from the commonplace, a basis for interpreting ideas of social propriety that only just began to be provisionally applied in aesthetic circles with the Victorian Era. Art at this point ceded the role it had up until Romanticism in the mid 19th century, paused halfway between academic studio practice as an eroticism borrowed from cultural alterity, viewed in scenes that depicted stories out of history and myth, scenes of violence toward or desire focused upon women. The major role of the nude is to reveal beauty—yet its type of beauty is drastically removed from the everyday. Lind reinvigorates traditional models vis-a-vis the Nude, into visceral tropes that serve to forcibly transcend commonplace aesthetic experiences.

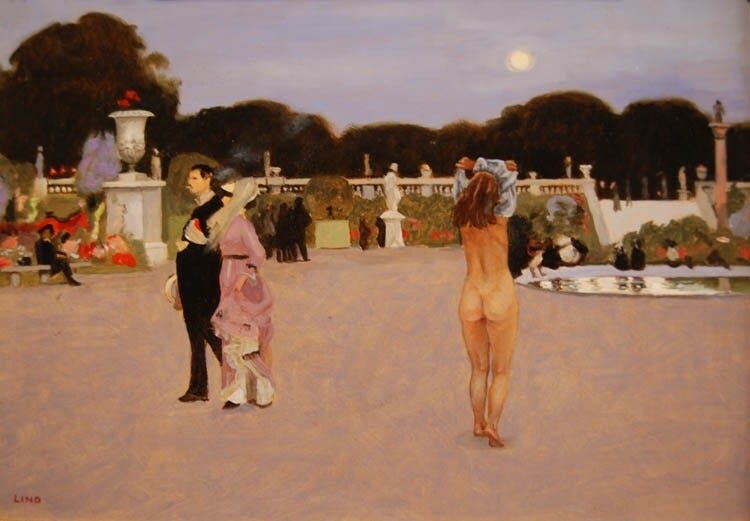

Lind depicts a scene of casual beach-goers in the style of Winslow Homer. The scene presented in Winslow Homer’s “Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusett (HIgh Tide)” represents a traditional model for aesthetic inquiry in its romanticizing of everyday life. Yet they instantly jibe with the presence of the nude which Lind paints into the picture. It is a strange occurrence, and seems to point to some social aberration. It generates a sort of aesthetic confusion, in which one begins to wonder which form of beauty is the more compelling. The juxtaposition of two narratives in a setting general enough to allow for them, creates dramatic tension, pulling the viewer in two directions at once. The Nude in this moment is a woman standing apart, her legs planted firmly, her hands on her hips, her gaze unabashed, and her self-determination readily apparent.

When speaking of a setting such as the beach, one has to understand how its context has altered over time and how its use has allowed for radical changes in societal norms. The bounds of proper society came head to head with the needs of experiencing the elements in Victorian society—the first era in which the notion of leisure time could be enjoyed by a newfound Bourgeois population. Lind is not merely addressing the urgency of classical beauty in a wide open setting divorced from courtly society, but the changes wrought by history itself, from Classical to Victorian, and forward, to modern or contemporary society. The virtues of bodily expression have come full circle.

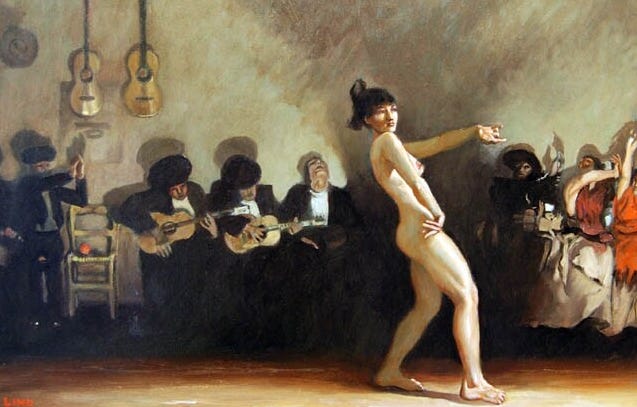

Though Lind chooses three major historical influences whose work includes the figure but not the nude itself, he does so with the full intention to transform the contexts by which we receive such imagery, and to make playful criticality of by using the nude, and all that it contains and infers, as a sort of ideological paintbrush–fleshing out the elements that formalize the idea of the real in each case. The insertion of a nude in both locations and contexts where none previously existed has a clarifying effect upon our perception. The nude in Lind’s hands is not an end in itself, but an opening into new ways of thinking about painting. Because the nude in itself constitutes a statement so pure—a presence of the innately human, and of the erotic, that its placement in visual contexts foreign to it will automatically energize our perception of the bases of representation and its role in constructing an idea of reality itself. The nude escapes the normal by awakening in each of us an idiosyncratically visceral response. Such as the case concerning works such Homer’s “Undertow” or John Singer Sargent’s “El Jaleo” in which a traditional scene is turned upon its head by the mere displacement of clothing. The drama of the moment remains, the gesture of struggle for survival or dancing to a sonorous tune remain constant. But the emergent nakedness of the main figures alters everything. We awaken to new ideas about previously viewed images in which they may never appear in their unadorned form ever again.