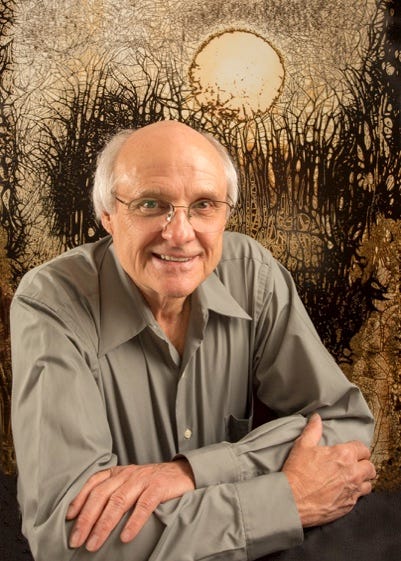

The Nolan Preece Story

PART ONE: The Education of a Photographer

This article is part of my Portrait section which is a limited series of articles on a single individual, combining an exploration of their creative pursuits with other interests and lifetime events. The first series, four articles long, tells the story of Nolan Preece, an experimental photographer living in the American Southwest.

The photographs of Nolan Preece are unlike any others that normally come under the name. They possess a strong quality of material accomplishment, show evidence of specific formal mastery and technical virtuosity in a manner both consistent and intense. They are for the most part abstract, although Preece can achieve narratives in his process, and has been able to achieve a mutability that anchors itself in the genre of landscape imagery. Overall, his process diverges from the mainstream methods and critical approaches to creativity that have come to be associated with photographic disciplines. The form for which Preece is best known is called a Chemigram. This form was originally developed in 1956 by a Belgian artist named Pierre Cordier. The concept was discovered when Cordier wrote a note to a woman using lipstick on photographic paper; he found that the chemical properties of the lipstick acted upon the chemically suffused paper in such a way that they achieved a painterly effect. This happy accident led him down the path of further discoveries in pioneering the method that Preece has made his own.

That said, the evolution of the artist never takes a straight path. Many life experiences and important figures filled Preece’s early life, superimposing upon his family background and inherited passions a frame of creative discipline and affinity. The convergence of all these elements and persons was the stew from which Preece was formed. He grew up in rural Vernal, Utah, within communities dominated by the Mormon faith, yet with a family that was extremely artistic on both sides. His father, Erland Preece, was a self-taught photographer, and his mother was a painter and ceramicist who had attended art school. Erland had a long family history in the Utah area; he grew up on his fathers farm, which raised crops and cattle. Erland spent many years of his young life riding horses. He participated in the annual cattle drives herding them from Utah to Green River, Wyoming where they were transported by railroad to Omaha, Nebraska to market. Under Erland’s guidance, young Nolan learned early on to love and respect the land. For Preece, photography became not only a way of looking at the world, but a means of grounding himself amid its myriad possibilities. It became an extension of the hyperlocal passions inherited from his family, such as ecological balance under constant threat from industry. What better way to express one’s beliefs, and to underscore a relationship to the world, than to learn how to depict it, and to present it as a means of truth?

Photography alternated in its use and its significance for Preece as he grew into adulthood. He became one of the primary yearbook photographers for the yearbook committee. The position offered him a greater variety of opportunities to develop his formal training, and the school also gave him access to other types of cameras. At the same time, Erland was continuing his educatlon by purchasing three important books on photography written by Ansel Adams: The Camera and Lens, The Negative (both 1948) and The Print (1950), each of which gave Preece a grounding in the practical aspects of the profession, and which also presented a paragon of photographic vision whose passions matched his own. During his Sophomore year in college, Preece was drafted and spent time in both officers’ training camp and away in Germany. In both circumstances, the photographs he took not only documented his experiences, but they also had a role in developing a further moral compass matched only by his technical virtuosity and interest in specific details. It was at Tigerland, at Fort Polk in Louisiana, where he took his “first war protest photos, which were images of the propaganda billboards spread around Fort Polk. Luckily, he was never sent to Vietnam. He dropped out of Officers Candidate School, and was instead sent to Germany as a tank driver. The photographs that survive from his Tigerland days and his tour in Germany ran the gamut between the depictions of propaganda posters om base and street scenes with people having fun and local vegetation. At the tank gunnery ranges he also documented operations and equipment. Preece was entering his journeyman phase, he states that “The camera felt good in my hands, I wanted the viewer to see what I saw. Roll film was expensive to buy and process so every shot had to count.” He recalled warmly the very beginning of his existence as a budding, or wishful photographer, using his Baby Brownie camera and processing his own film in his Dad's darkroom at the age of six. That seemed a long way behind him, though his story had much further to go.

In 1968, Preece matriculated at Utah State University. He knew in his heart that photography would be his major. This period in his life was a major turning point, when the influences that had been used to shape him in his younger years, would be made palpably present and immutably necessary. The program at Utah State was at that very time being just then transformed by the influence of Ansel Adams. Adams had made a deal with Utah State that if they would advertise his Friends of Photography workshops, he would send a group of West Coast photographers to give lectures and critiques, and to organize exhibitions. Preece attended workshops given by Al Weber and critiques by Ruth Bernard, in which he learned what a truly magnificent photograph should look like, and how imagery speaks to us in different ways (sic). The method that Adams taught, as handed down by his workshop leaders, was the Zone System. One learned how to expose the shadows in each picture, finding a tonal midpoint across several areas, and identifying each according to the apparent depth of shadows. Then, one could develop the final print for the highlights, creating complex images with different gradients of tonality in different areas. One could actually reduce the tonal character of each exposure to a numeric value that would allow them to reproduce the same image with relative certainty. This degree of control, married to a sensitivity of tonality, was what made the Zone System revolutionary, and which contributed to a whole new generation of photographers, of which Preece was one. (4)

Preece graduated in 1972/3 and spent the next few years at various jobs, such as building summer homes and working on the generator for a wheat farmer. The most notable occupation he held during this period was as the darkroom technician for The Herald-Journal in Logan, Utah. He developed all the film taken by staff photographers who were sent out on assignment to cover newsworthy events and occurrences in the immediate area. He started graduate school at Utah State in 1977.

For his senior thesis in graduate school, in 1979, Preece began in earnest to investigate the experimental forms of photography for which he has become known. Since the program at Utah State was primarily based in traditional fine art photography, inclinations toward experimentation had to be explored in his own time. At this time Preece discovered the historically marginalized but technically impressive discipline of the Cliches-Verre. The most recognized method of creating a glass print was established by Camille Corot and the Barbizon artists, was by inking or painting all over a sheet of glass and then scratching the covering away to leave clear glass where the artist wants black to appear (1). Almost any opaque material that dries on the glass will do, and varnish, soot from candles and other coverings have been used (2). Preece differentiated his process from the historical method by adding a stage and then using digital technology to alter the print after the fact. As he states on his website, “I used solvents dripped on smoke-on-glass to create a matrix that is then printed with an enlarger on photographic paper.” I had stumbled onto a unique process. (online) “The strange and odd beauty of these cliches-verre produces images which can slightly startle the viewer. Extreme detail and sharpness are the exquisite attributes of the image” (Ibid).

Unlike Corot and others, Preece was not interested in recreating some naturalistic scene, akin to a painting or etching. He was at something radical, which was by necessity abstract. Preece made an extensive study of the historical models of Cliché Verres that had come before. The main difference between these and his own was determined by his interest in non-objective imagery. Preece felt strongly that he had to break with assumed notions of the form. This would also allow him more freedom in the process of required experimentation that would get him to a level of beyond that of a beginner. These works had to be rigorously impressive as well as formally divergent from traditional fine art photography.

The forms which Preece achieved in this first new experimental series were a decided break not only with the recognized Cliches-Verres of the past, being abstract—or as Preece prefers to call them, non-objective—but they were also a culmination of everything he had learned in creative means up to that point. They were photographic in that they were realized using photographic paper, and via an established process that had long been accepted as contextually photographic. They combined the realization of obsessive, strangely anthropomorphic marks, dragging their forms across the paper like one does in printmaking, to create eerie forms that resemble alien flora in distant worlds.

Preece has always made his discoveries his own. When one lives in a certain territory for so long, it ceases to be merely a surrounding atmosphere, it becomes a home—a site for nurturing what is there and perhaps even creating something new from the same elements. Being “non-objective” these cliches-verre images could push the boundaries of the possible while at the same time challenging perceptions of the viewer. They were to pre-shadow Preece’s future explorations beyond the darkroom.

The title of this section has specific connotations. It references the traditional laboratory of the photographer: the darkroom, a space to which one must by necessity remove oneself in order to process film, a zone of reduced spectral engagement where the technical and inspired procedures of creativity can merge. Yet if Preece’s success as an artist proves anything, it’s that the limits of preconceived creative realization go hand in hand with perceptions of one’s own self. In Nolan Preece, we are presented with an exemplary example of the contemporary artist that does not conform to the usual stereotypes. Artistic identities have as much valence and diversity as creative disciplines. They are determined by a broad context of factors that emerge from, and operate upon their production. Chapter Two will present the continuation of the Cliches Verres, the beginning of his Chemigrams, and further life experiences that informed Nolan Preece’s practice, his world-view, and his future developments as an artist.

End Notes:

Griffiths, Anthony, Prints and Printmaking, British Museum Press (in UK), 2nd edn, 1996.

Schenck, Kimberly, "Cliché-verre: Drawing and Photography", Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 6, pp. 112–118, 1995.

Preece, Nolan. https://www.nolanpreece.com/page-7--about-the-work.html

Line of thought paraphrased from “Anselm Adams—A Beautiful Life” by Rob Cook; https://robc224.wordpress.com/2022/08/20/ansel-adams/

[I highly recommend this essay for anyone wanting to learn about Ansel Adams!]

DAVID GIBSON is a freelance writer in the arts. He is available to write essays for monographs, exhibition catalogs, text for web sites, grant and residency applications, and to provide critical thinking in matters of portfolio development, studio practice, and professional etiquette. He can be contacted at davidgibsonwriting@gmail.com