When I first met Raphael Zollinger several years ago, I witnessed an artist who was very much involved in penetrating the mysteries of his own history, and achieving this in a manner that engaged with appearances, their origin and justifications, and the role of images themselves. This work is part of an ongoing documentation that chronicles the path of a family's immigration, starting in Lithuania in 1917; taking them through Europe, South Africa and eventually to New York City in 1989. What began as an experiment with the few collected images of his family's migrant history has morphed over time into an engagement with the power of images. Zollinger could easily tell you a story from each original picture, though the grand path of his family history has become progressively tenuous. Though family and place abound in them, there is a struggle to achieve meaning in the most minute of moments, many of which are lost to memory. As the artist explains:

“All of the original photographs are found. They were discovered after the passing of my grandparents, on both sides, in boxes and in albums, many of which I could not identify. The dissonance between my connection to the images and the shift in time and space were palpable, meaning they were depicting both family and at the same time strangers. I am not close to my extended family since travel and migration/ immigration have been a constant throughout my life and for many generations prior. For various reasons, including the persecution of Jewish people, political and social unrest, part of my family has had to move every 2-3 generations and I have followed this pattern having moved to this country as a young teen. Growing up, my extended family all lived in multiple time zones and hemispheres. Identifying and extracting patterns has become a part of my work.” Zollinger addresses the original events not only with images culled from the family collection, but with how vagueness can create esthetic ambivalence. These images depict a time and place as worn histories made monumental and tactile; establishing a loose narrative of faded colors, and blurred memories. These are the marks left behind of people who do not identify with a nation or state; they adapt, merge and blend, fluid and dynamic.

Evanescent Tales / Fragment #11, 2014. Pigment print on aluminum, 24 x 30 inches

It’s natural that when we look at a work of art our conscious mind takes over and we begin to rationalize the subject or theme of the object within our attention. We all share the same instinct not to accept things as they are, but to impose interpretations upon them. In our childhood we lay on the grass looking up at swirling clouds. We saw things in them, if only for an instant. This was our brain filling in the blanks. That the forms faded as quickly as they appeared mattered less than if they have never appeared at all. The child understands abstraction because at a certain level, everything he receives is abstract until it is not. Abstraction is the true starting point of our engagement with the natural world, with reason, and with the kind of knowledge that ultimately matures us as we grow into adulthood. If an image or impression does not immediately justify itself, then we are left to imagine what it could be, or to let it be unreal. Let it be merely the elements of an impression endlessly presented. Of what we see in Zollinger’s work, we can say “That’s a piece of paper…that’s a photograph, or it once was one. Now it’s a fragment, degraded and transformed by reproduction…an artifact of a lost memory.” The concept of history rears up its head but is summarily ignored. These supposed fragments operate just like rorschachs or intentionally abstract paintings based only on color and mark. The closer one looks at these images, one begins to notice the appearance of paper as an object or esthetic surface. One sees fragments of places, things, and people.

“A reframed fragment of the most degraded area of photographs become my subjects to create new images that elevate the photographic object’s history, handling, and deterioration to monumental status. Reminiscent of artifacts, these works establish themselves as memory objects that have lost their indexical references to reality. Through this reframing, distancing and doubling, these works function as a lens looking at the past, by way of imagery carried on the surface, while remaining firmly rooted in the present, by way of the object’s digitally derived facture.”

Zollinger is interested in the liminal state of the photographic image, where representation merges with abstraction and the non-verbalized languages of photography, painting, and sculpture collide. Zollinger sees a photograph as a manifest image, like a mythic symbol, an image flickering within human consciousness, what Jung called the "psyche". But he also understands that the practice of photography has reduced what was once a unique print to a serialized cipher that exists as data in a computer file. The object in the picture is likewise suppressed, and ceases to be such a presence in our lives. Zollinger believes that even within the procedures that create photographs, that surface detail can create a context for our recognition of the image, and he wants to add to our primary engagement with that surface by loading it with marks, by making it hard and heavily inscribed. Zollinger's relationship to images is central to his aims and accomplishments as a creative individual. Yet his choice of images, his ambivalence, and the procedures and models he melds with them present a radically different idea of what an artist is. Zollinger has chosen to accept the unreliable and obfuscating elements of memory and fill in the blanks with strategies of his own.

Evanescent Tales / Fragment #26, 2015. Pigment print on aluminum, 32 x 40 inches

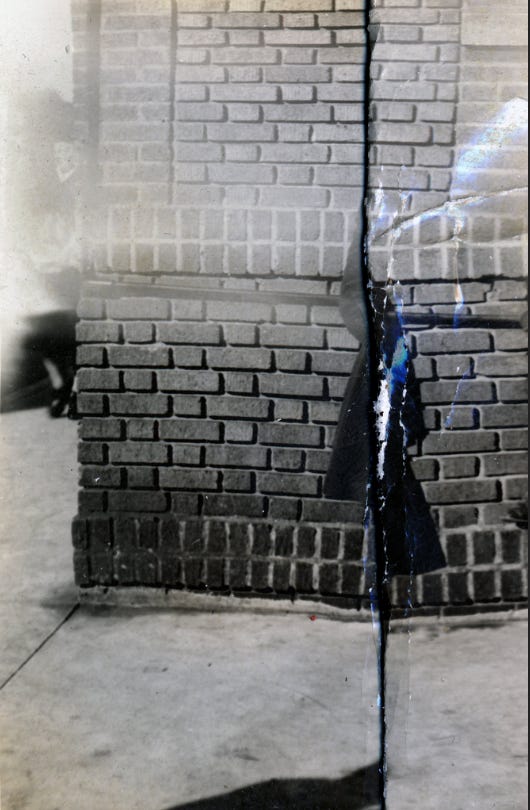

Two particularly arresting images from his Evanescent Tales series are “Fragment 11” (2014) and “Fragment 26” (2015). They are each comprised of a small piece of an old photograph that’s been torn from the whole, or may itself be the last remaining part of an image that once contained people in his family or their friends, a favorite place, or an event that recurred often, like a family picnic or a regional event. It could be at any location in any country from any decade of his family’s migrations. What remains is the shadowy lower limbs of a large tree in deep summer, all of its leaves on the branches, and ample sunshine flooding through them. Such a tree would have shaded generations of readers, young lovers, or family gatherings. It would have been shade from the sun, cover from the rain, or a playground in its branches for young children. The other image is view of a few people walking along what seems to be a beach, wearing sandals and sneakers, their legs bare, their shadows like solid bodies in the chiaroscuro of overwhelming sunlight. Half of the image Zollinger presents is the edge of the recognizable image, raw and discolored from possible water or fire damage, but creating a liminal or littoral area where the imagination erupts. The surface of the pretreated photographic paper has had its own elemental reaction to the ravages of time and the accidents or erosions to which such a sensitive material is heir. We see a photograph that has ceased to be merely the documentation of a pleasant event, and becomes an artifact caught in mid-ruin, no less beautiful.

Invitation to Lost Time / Interior #14 - Alex, 2017. Direct to substrate pigment print on aluminum, 63 x 46 inches

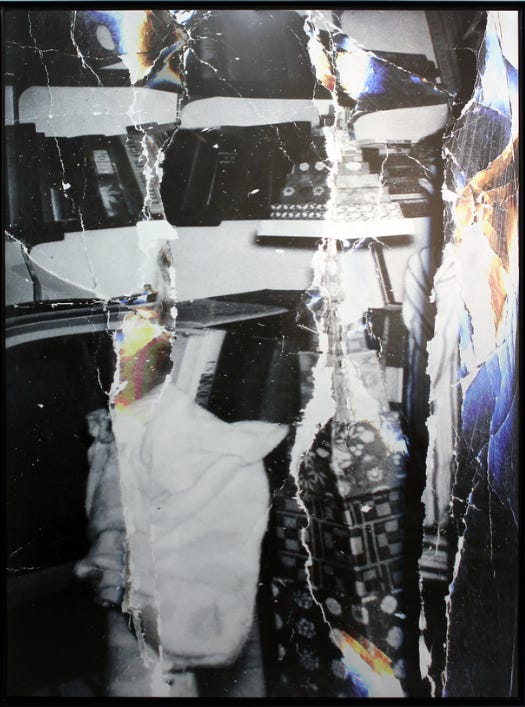

Zollinger’s following series was Invitation to Lost Time (2016-2017), which involves less deconstructed images that have much more visual area, and the decay of them has taken the shape of areas where documents were crushed or folded, creating creases that sometimes destroyed the most important, detailed, or narrative elements of the image. Scanned in whole, with only the most minute edges recombined, these mostly black and white images with deep dimensional and structural forms in them create strong ambiguities for the viewer. “Interior #14 Alex” (2017) shows a couch sitting in a musty room besides a standing lamp with only a wide blank wall above it. The figure originally pictured, named Alex, is inferred only by naked edges of shoulders or legs and a minute tuft of hair hanging disembodied in the airless living room. The couch looks comfy, a dark color, with ornate flowers in red and gold and vines everywhere connecting them, like a garden. It looks well used, a place where couples have cuddled, or where someone has sat many an afternoon or evening, enjoying peaceful domesticity. The photograph is heavily creased, as if it had been rolled and kept somewhere more flat than necessary. The rip in its middle right where a figure shows its most cryptic body parts plays a double entendre of intimacy and violence, as if it had been done intentionally at some moment in the subject’s past, an act of vengeful passion. To rip another out of an image or to rip oneself is sometimes about the image and more often about how they feel about the subject; that the image was kept after being partially destroyed shows how strong an effect the image had. It was perhaps a bad memory but not a bad image. Having been so edited it became something worth keeping, even in its reduced status as a document. In considering this dynamic we can also think an image like “Exterior #14 Silvia” (2017). Similar to Alex, Silvia has been excised from memory. The scene is a bit more loaded, taking place as it does in the street, where anything that happens could also be observed or interrupted. The implied intimacy of these portraits heightens their narrative’s import. Of the figure in the street we see only the lower extremities of a woman’s trench coat and a shadow at our feet, presumably hers--as it is widest and darkest near her. The pavement below and the brick wall behind could be anywhere. past the edge of the building the street continues and we see the legs and feet of a woman wearing patent leather shoes, making this image one from mid-century. A face seems to peer back at the photographer, but it looks more like the sneer of an advertising caricature than any known person’s visage. The weird appearance of an accidentally portrayed other magnifies the psychological portent of an otherwise muted image.

Invitation to Lost Time / Exterior #14 - Silvia, 2017. Direct to substrate pigment print on aluminum, 45 x 63 inches

The third example from this series is more narrative and more destroyed all at once. “Interior #6 Emma and Bookshelf” (2017). The scene on hand is a view of a set of shelves filled with large three ring notebooks with typed labels on each, of the sort familiar to me as the sections of an archive of photographic slides, press releases, and biographical materials found in art galleries back in the day. These books are all black and they are in a state of some disarray, spilling cross gaps in the storage on each shelf. leaning here and there, sometimes stacked and left there. They could likewise hold any official material such as financial ledgers or medical test results, or maps and deeds. That they are large and officious and hold something important is strongly implied. Elsewhere in the photograph there is an overexposed figurine with a misshapen head and deep grooves as the lines of clothing or facial expression. On the other side of the figure, in a foreground area nearly completely obscured for being on the very edge of the scene, is the silhouette of a woman’s body, clothed in an ornately designed dress of tribal style, we see just the outline of a breast. The are where the rest of her figure would be has been overexposed, possibly even in the process of scanning it to be reprinted by Zolinger, and a reflective color erupts from that area, like light reflected by a stained glass window. The oblique character of this part of the image is a doubly ambiguous memory made categorically difficult but also aesthetically intriguing at the same time. The creases and tears in the image are like seismic data showing how time has decayed the event yet left questions for both the artist and ourselves. Taking pictures is not only about creating an endless register of personal historical facts, but of containing the emotions. Sometimes we take the pictures because we want the moment to end. We take it so that we can forget. Zollinger shares this with us and that’s a memory worth keeping.

Invitation to Lost Time /Interior #6 - Emma and Bookshelf, 2017. Direct to substrate pigment print on aluminum, 47 x 63 inches

I hope you enjoyed reading this post, the first in a new series about contemporary photographers. Please share it, and consider subscribing.