SIGHT INTO MIND

3-D Experimental VR and Art Practices: Untangling Another Dimension by Rebecca Hackemann, Ph.D. Bristol & Chicago: Intellect Books, 2023

How we perceive the world means everything to us. Perception drives belief. Belief gives us our habits, and our rituals. Creativity is nothing without perception, for even in its ability to invent new perceptual procedures, leading to critical métiers, it relies upon the recognition of the real. Certain artists have made transforming reality their specific mark. In her exploration of 3-D Experimental Virtual Reality, Rebecca Hackemann presents a rigorous critique of the history preceding, and issues surrounding its relationship to contemporary art practices. Hackemann brings together an array of different artists, whose work uses stereoscopic technology to present divergent constructs which question realism as the basis for truth while simultaneously emphasizing the use of archaic media to tell contemporary stories. But this type of technology, though impressive on its own, and occupying a singular position as regards its use in art, is not the end. Hackemann also presents a vigorous and thorough case for the next step in technologically aided perceptual tools, meant for the extension of speculative vision in society, which we now call Virtual Reality. Hackemann devotes an entire chapter solely to explicating the work of some two dozen artists whose work has utilized the stereoscope, complete with images that are presented in 3-D format with a pair of 3-D glasses accompanying the book. This enlivens the imagery, giving it the sensory immediacy that real images in a stereoscope would impart. I found two artists in particular especially effective in their use of the medium. Christopher Schnebeger used the stereoscope’s three dimensional visuality to present narratives in which surreal and eerie facts present the life of an inventive if damaged persona, traumatized by the loss of her legs but projecting the idea that she can levitate, and in doing so, somehow transcending her limitations with fantastic extra-ability. Ethan Turpin presented isolated scenarios in which social issues and structures of society were simultaneously critiqued.

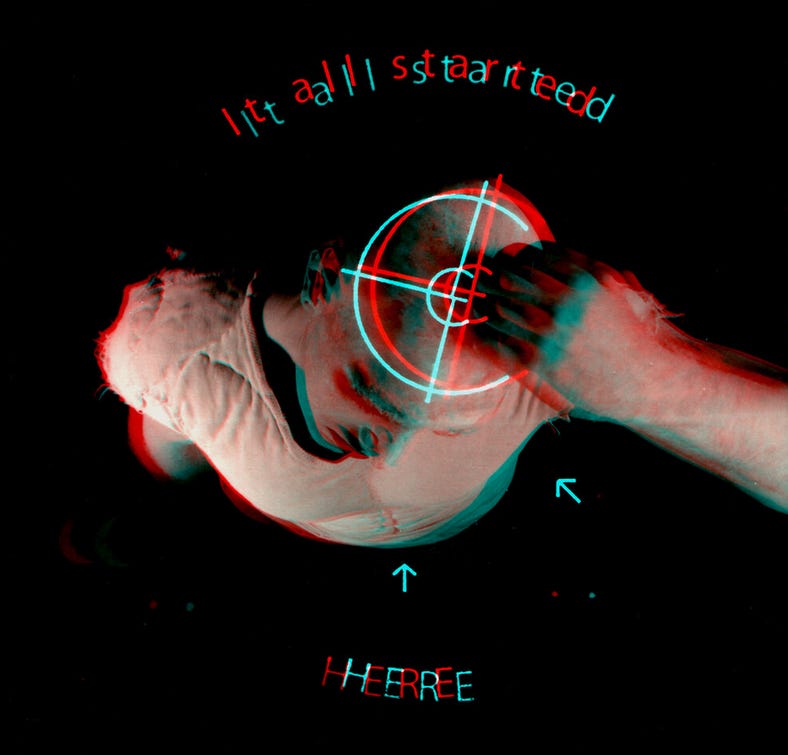

These two examples begin her critical narrative, and each in its own way is extremely telling. They are unified by the use of the stereoscope, an invention that was used in most cases for its innate entertainment value. Various venues hosted a stereoscope, they might be in amusement parks, department stores, or a children’s shoe store; anywhere that a degree of wonder can be achieved by onlookers who are curious and can, in that interval, give their attention to what is provided. Turpin’s work in particular presents his reinvented scenes on speciously recreated placard of the sort used by the earliest models of the machine. Hackemann’s study includes the work of a dozen more artists, including herself, for she is an active artist working in the vein of stereoscopic photography, creating optical experiences that mine and mimic vintage profiles of mass-produced images except that in her case they are singularly oblique, presenting opaque and minimal imagery that interacts with text elements to present emphatically prescient statements. These are presented as immersed in the darkness of a viewing chamber, and they float like bubbles in an immense sea of spatial recognition.

The concluding chapter makes an in-depth exploration of the most recent aspects of her study in the techniques and disciplines utilized to achieve immersive experiences in which art bleeds over into life, identified as the future of perceptual mechanisms, the 3-D Experimental VR of the title. This is the second half of the subject at hand, and one that matters in ways more than what was previously achieved, has to do with technological advances in three dimensional virtual reality, and how that presents exciting prospects for the future of innovations in artistic practice. Hackemann delves into the current archive of established VR works, some of which date back to the early 1990’s, when the art was in its nascent phase, and was known to a much smaller critical audience, most of which were also creative practitioners of the form. Hackemann traces the emergent realizations that led beyond mere speculation during epochal progressions from the use of dioramas to actual technological construction of virtual environments. Hackemann realizes that although her subject is both compelling and necessary, it’s advisable to take a gradual method in arguing its case, so as to ease into complex phenomenology from a position of comfortable esthetic comprehension. She wants to extend the exciting prospects for her subject matter to new minds. Indeed both the prospects for Virtual Reality and its accomplished models bespeak a new and radical perspectival turn that stretches well beyond the notions of Cartesian space. Photography, which from its origin in the 19th century up until now, has represented the reinvention of the wheel as the most differentiated perspectival métier, is now thrust back into the margins by an evolved discipline that delivers us into new environments that are not only prescient but are numerous enough to replace all former ideas of art.

One example is “Osmose” (1995) by Char Davies, an immersive VR experience for which the participant must wear a VR visor which are connected to a harness with enhances the sensory aspects. “It uses 3-D graphics and interactive 3-D sound, a head mounted display, and real time motion tracking based on breathing and balance. The idea of navigation through breath is in and of itself unique and meaningful, a counter-narrative to the joystick or buttons. The breath and focusing on it is a benchmark of most meditation practices—by navigating with and through the breath, its pace and depth force the [user] both into focus and relaxation…. We are greeted by a monotone environment with wispy computer sounds and birds chirping, a dream-like silvery landscape…. One can journey anywhere within these worlds as well as hover in the ambiguous transition between the spaces (Hackemann, 39-40).

Another example, and one more recent, is the work of the artist collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, whose work “In The Eyes of Animals” (2017), provides a sequential series of immersive experiences that evoke and replicate the quality of actual sight by a dragonfly, a frog, and an owl. The experience requires the user wear a globelike cowl that completely closes them off from any other sensory distraction. “Actual Lidar scanners enable the artist researchers to scan the forests of England and build environments in 3D stereo. This technology enables the participant to escape and imagine seeing flowers as bees might, using different visual spectra. The experience is designed to be had in the woods, with a shift from the human visual spectrum to that of a dragonfly or other insect’s vision. While it is passive (the person wearing the headset cannot explore alone or move around), the quality of the sound and imagery far exceeds most VR works and reminds us of the magnitude and importance of empathy and nature (Ibid, 43).

In Hackemann’s concluding remarks, she addresses the need for 3-D Experimental Virtual Reality as an art practice to continue what she calls a spatial turn, a progressive moment away from the limitations of the two-dimensional picture plane, which only extends via technological means the same perspectival modes that have been dominant since the Renaissance. She urges artists and the art-oriented public to embrace the artists and ideas that are moving this “new” aesthetic discipline forward. She acknowledges that despite the strides she has taken to expose and expand recognition for the historical development through stereoscopic and 3-D Virtual Reality creative endeavor, that there is still a long way to go, and that she may be writing another book. She references a section of media links from which people can access models of the actual artworks. She has made a substantial contribution to a societal appreciation of these ideas, and has us all looking to the future.

DAVID GIBSON is a freelance writer in the arts. He is available to write essays for monographs, exhibition catalogs, text for web sites, grant and residency applications, and to provide critical thinking in matters of portfolio development, studio practice, and professional etiquette. He can be contacted at davidgibsonwriting@gmail.com