SPECTRAL INTENTIONS

1997: Not Vital At Sperone Westwater

When I was a young man visiting galleries, I can remember only a few instances of an artist who mined mystery while simultaneously evolving forms of spectral beauty. Vital's solo exhibition at Sperone Westwater in 1997 was especially memorable. I was supposed to write a review for Sculpture Magazine, but this never happened. I still have my working draft from that time, which is now a map of my thinking if not the actual meat of my memory. Looking back to that one expansive moment, I still recall my reaction to the work, and how it stayed with me, vibrating in my mind.

In his current exhibition, the streamlined sculptures of Not Vital continue to embody a union of conceptual and formal ends. One series of works attends to the biological imperatives of history and prehistory. Minus, Zero, and Plus (1996-97) each consist of green rubber garbage cans with modified silver covers. Each cover has been made to represent one level of human evolution with a single representative design. Minus shows the rough, studded hide of a dinosaur or early prehistoric animal; Zero, the exact replica of a man’s rear torso; and Plus, a plain, smooth cover except for a single square and solid spine, like a reduced and futuristic dorsal fin. Each of these sculptures relates to an idea of our physical existence and attends to ideas about our skin, how our coverings makes us what we are in time, organisms altogether vulnerable. They also apply to man’s development in history as being biological in addition to cultural. In representing the present epoch in human evolution by the rear view of man, titled Zero, does Vital mean to infer that we are nothing now, or merely that our present state is only qualified by a leap into chronological distance? There is a sense palpably expressed here that the future holds promise, for then we are Plus. What would being Minus qualify us for? Vital does not preach nor does he let on as to his intention. We are left to feel that any judgments on man as a species are arbitrary at best. What remains is the vision of the artist.

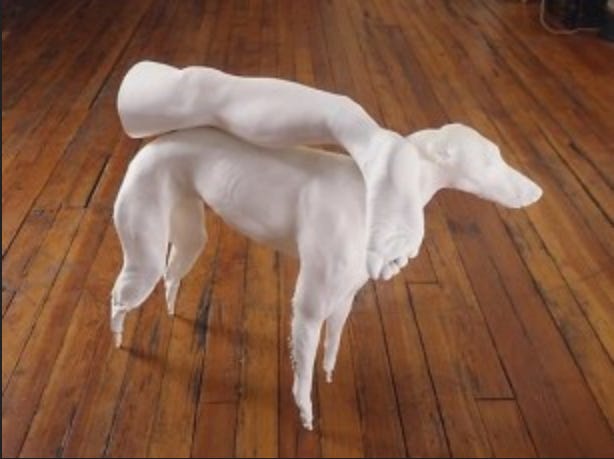

Greyhound Carrying My Broken Leg (1997) is perhaps the most well-conceived work in the exhibition. The naturalistic figure of an average greyhound dog stands erect in the center of a square room, balancing perfectly upon its back the lower leg and foot of a man. Vital explains this as the leg he broke when skiing as a boy in his native Switzerland. In the history of representation, the greyhound has never referenced labor; they were the pets of the wealthy and privileged. The dog’s face lacks vitality, becoming dreamlike and enigmatic, presenting Vital’s interest in the opaque aspect of sculpture.

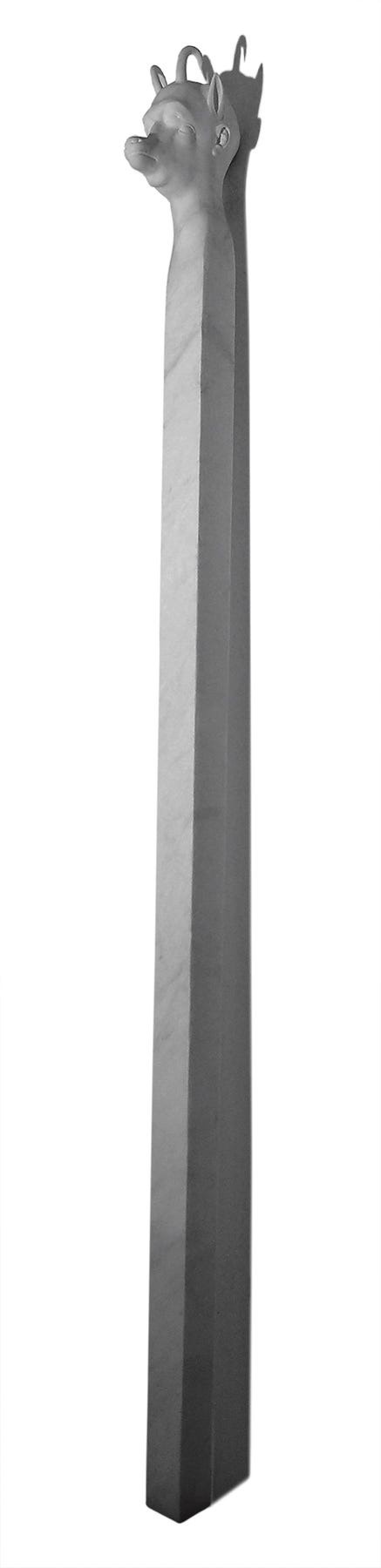

1/2 Man 1/2 Animal (1996) presents characteristics of each species as combined atop a tall totem pole otherwise unadorned, and smooth to the touch. The face at its top resembles no man and no animal that we know well. In Snowballing The Giraffe (1997), the skull of a giraffe, hung the height of a living animal, has been made the target of snowball target practice. This work projects an impression of warmth; the dead skeleton of an animal defies the violence made upon its last extant form. Yet its placement beside the other sculpture seems more than merely idiosyncratic.

Much of this exhibition focuses more generally upon the idea of reference than the motif of the universal animus represented between man and animals. The present direction of his work seems to bend more and more toward a pure understanding of the ideas behind form. This is achieved not through a mindless repetition in the casting of forms, but in a narrative process of thematic sculpture, what Claude Ritschard calls Vital’s "binary" process of alternating his concerns between perceiving the figures as drawing and as icons. This is exemplified in all manner of forms, whether large or small, whether essentially iconic as sculpture as within the context of a an installation. Small Tongue (1996-97) is a good example of this. Modeled from the real object, it achieves a singular effect over the wall space of the entire gallery with hundreds of models made from unique originals. The tongue’s function is to punctuate the infinite experiential space of the gallery by impinging upon a free visual field. The tongue can be seen as a protrusion or visitation of animal consciousness, or as a tasting of experience by the animal persona not otherwise present. This creates a feeling of anxiety in the viewer, unsettled by the presence of an incomplete being whose absence is in some manner his or her fault.

Vital’s process is similar to that used by Luis Bonuel and Salvador Dali in envisioning their collaborative film Un Chien Andalou. They each suggested an image, and through a process of mutual editing worked out of cosmology which evaded immediate association with some universal idea, such as a dove suggesting purity and peace. They wanted only images that proved complex through their perversity and their opacity. Despite its reliance upon ambiguity, Vital’s work is initially curious in an open handed manner. He has succeeded by way of a progressive spirit, an orthodoxy of aesthetic purpose which combines forms and ideas to create a conceptual narrative which flows through all of his pieces, actually creating for the work a future which remains both objective and concrete. He does not romanticize flora or fauna, nor does he lobotomize human concerns, no matter how trivial or corrupt, by use of a specific moral message.

Unfortunately, because this exhibition occurred so long ago, and the artist has since moved on to very different work, there’s little online presence, which is to say proof, of the works described here. Some have been remade in epic proportions while others are contextually obscured by the new work. Looking back upon these words I am both pleased and surprised. One forgets about the intellectual machinations of one’s younger self. These pages I wrote then show a willingness to gage the quality of encounter, and though the writing is left incomplete, it points in a direction whose destination is now much more assured. Of the greater number of artists in the Nineties, few had philosophical intentions equal to his. Vital’s work eschewed the weight of a moral compass and intuitive aesthetic similar to Wolfgang Laib or Joseph Beuys. His work would be equally at home in the mountains of his native Switzerland as they were in precious galleries. If one came upon them in a more wide open natural context, one might assume that here was a message from the past for the future. A spectral presence asking questions answered only by time itself.

This is interesting. The work seems a bit uncanny, spooky -- which may be one response to overly conceptual art, disturb the thinking . . . Anyway, thanks.