I first met Janice Caswell around 1994 through a mutual friend who has since left New York. I was still generally unaffiliated at that time, a non-artist in the art world with critical aspirations. Having grown up around art dealers in Soho, I was just then beginning to visit studios, and hers was among the very first art that I was seeing where it was being made, and not just where it was commercially exhibited. What I saw reflected a personal reality in which parts and details really mattered. To me, it was about intimacy.

Caswell was making artworks that resembled maps. She was clearly interested in describing the mutable character of periodic experience as viewed on a grand scale, and found its most successful manner of expression in a format that begged to be reproduced and reinterpreted. These were placed directly upon a wall, later to be contained in boxes covered in glass. What most attracted me to Caswell's work back then was how it combined order with ambiguity. Unlike a published map, that in some way exacts a sense of dimensional contingency, Caswell's versions played freely with the idea of a map as a visual correlation between fact and memory. She had succeeded in exploring this form of art making to the point that her installations could be sold as framed events. I wondered how long this version of her interest could be sustained. Vision travels where it needs to go, even if it has to travel far afield to return with fresh evidence.

After working in this way for about 10 years, my focus shifted to ideas of structure, order, logic, and the impossibility of perfection. I started experimenting with collage-and-ink drawings in which small squares and rectangles were lined up and stacked in a regimented way that inevitably drifted away from the grid, creating imperfect geometric forms. After spending a few years building these forms based on a wonky grid, I began seeing and being attracted to similarly irregular shapes in the world, which led me to the work I’m making now. [Pierogi Q&A, April 22, 2015]

Caswell's current work is split between a few genres, most of which is work on paper, or work utilizing cardboard and collage. The others are photographs which have been drawn or painted over to obscure certain elements, highlight others, and in general expand the purview of negative space. The last is a sort of secret body of work, the ink drawings that were inspired by the manipulated photographs, which currently exist only in notebooks. Direct enough to seem childlike, they also succeed as precious and indeterminate sketches that show how her ideas take root.

What we discussed first were the manipulated photographs, perhaps because they were the earliest of her newer bodies of work, yet still in development, and ranging in effect from versions that had been obscured with the straightforward application of acrylic gesso, many others in which a fluid covering was aided by a layering of the image, a drawing into it, which resulted in a compound obscuration that complicated a reading of the image as a traditional representation while at the same time making it more visually dense. This either triggers an impulse in us to engage more aggressively or to give up and let passive reflection take over.

I never give up on an image once I start looking. I find that it's all about asking the right questions, and being that I was in the presence of the artist, I could ask all that I wanted. My most pressing concern when it came to the original untouched image was its context of origin. I wanted to know if she had taken the photographs off Google Earth. Now if you feel this was presumptuous, consider that I come upon a lot of work that utilizes technology, in some cases as a creative shortcut, in others just because it is there.

Caswell reassured me that all of her images were taken in person and on site. If an angle looked extreme that meant she had found a higher vantage point. The integration or commingling of myriad colors was accentuated by the printing process and by the perspectival erasure of the manipulation so, but that was all. The true colors of the image could be brighter and the lines cleaner and harder but the rest was a real place as seen from an unusual vantage point.

Caswell's photographs are not however limited to locations, but also concern solitary objects culled from close up images in which one particular element, the one that survived the manipulation process, was a part that stood out for her. In one image (they are all untitled), we are faced with a scene in which three quarters of the original photograph have been whited out, leaving only a rhombus close to the center of the paper. What the resulting image most resembles is the space where two buildings meet, mildly reminiscent of a Gordon Matta-Clark work, in which the marginalized zone between two structures can become a viewfinder for other perspectives or an element of tension to unite disparate objects. Both structures are made from wood--like homes, barns, or any old fashioned industrial structures as may be found in any out-of-the-way area.

They have been photographed in such a way as to dramatize the colors and surface details of each section, the seeming divergence of areas that, if they had been documented in a more straightforward manner, might have formed a more logical tangent of appearances. As it is, the image is so displaced in all aspects from its original state that we are constantly turning it around in our minds, looking at each part and wondering which of them goes first in any approximation nearing an idea of what is real and what is not. In a second photograph, several areas of an image have been particularized to stand out as disparate abstract elements that are so random and accidental looking as to confound the viewer in trying to rationalize them as part of some greater yet invisible whole. Perhaps what generates the drive we have to recognize each element is tied to our association with the source material as a photograph—otherwise considered as document of real things, places, or persons.

But it is never Caswell’s intention to present any sort of real dimension, rather to extrapolate visual elements from photographic images that will enact an abstract event. The fragmentation and the erasure which provides a spatial ground for it to take effect are implicit denials of the real. With its separate sections of revealed detail only a sliver, they presented, alternately, the textured superficial appearances of metal machinery, tin shacks, highway concrete, and tiled linoleum floors. In depiction they seem to form a wave of ambiguous planar references, almost a tapestry of elements all associated with hardness, with utility, and with the worn and defaced fronts of spaces across which multitudes moved before she chose to use them to elicit a sensory effect. I have a feeling that complexity is not something she looks for but all the same it arises as a product of the amorphousness at the center of her explorations.

The biggest challenges arise when I’m working with very complex images. Sometimes a piece seems to have an infinite number of possible outcomes and I feel temporarily paralyzed, unable to choose a path. And with each decision I make–each section of the photo I white out–part of the image is gone, and the available options change. When these pieces are finished, I’m not always 100% sure my choices were the right ones, even when I’m very happy with the result. [Pierogi Q&A, April 22, 2015]

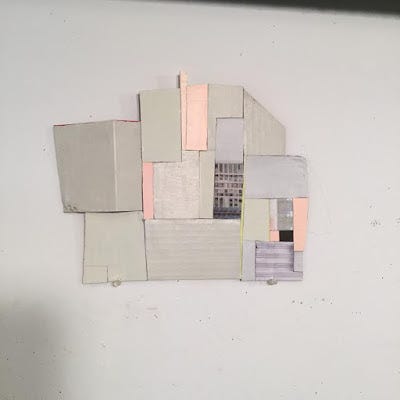

The second body of work we discussed during our visit were her colored cardboard wall reliefs, which utilize only paint and sections of cardboard organized into random organic and geometric shapes. In her studio they covered the longer of the two walls, each being small in scale, but combined they formed a series of satellite figures each with its own combinations of sections, colors, silhouettes, and protrusions. On certain ones a small area had a collaged media image pasted into them so as to create a break between areas of pure color and add some ambiguity to the reception of the relief silhouette by adding a phantom silhouette in a smaller area within it. The wall reliefs actively combine color and form and their most defining element is the idiosyncrasy with which each relief work is made, by how many parts, perspectives, and how much they are built up and away from the surface of the wall. They take on an animated quality that makes us look at them as if they were little blocky life forms, atomic structures growing out of the wall rather than merely placed upon it. When I really look at them, and perceive the combination of elements, I begin to discern an internal structure that begins to look like a color coded stand-in for an actual photograph, with certain elements like a swath of sunlight dominating the background, or the entire image constructed of uneven squares in alternating grays and blue grays reminding me of some futuristic modern housing complex. A red L section in one work with a black to purple background reminds me of a window at dusk with the fading shadows of dusk turning to the quickening darkness of night. Looking at these structures I am reminded of the simplicity of paintings by Paul Klee or Henri Matisse in which certain forms, no matter how minimized in character, dramatically intimated trees, animals, lakes, mountains, and people. Caswell likewise captures the essential silhouettes and moods of images she has taken with a camera somewhere.

The last series we discussed do not have a name but I refer to them as her secret drawings, for they exist only in a sketchbook. According to her they were instrumental in her envisioning of the previous two series, they were the missing link between the photographs she took upon various travels, the dimensional and spatial elements translated into artifice which he then placed into certain bodies of work. They certainly stand on their own. Looking into her sketchbooks seems indulgent, a trespassing of sorts into the territory where raw ideas become the potential for expansive oeuvres. Untitled again, they could easily be named for the associations they suggest. In many of them there are grids, suggestive of lattices over windows, grates in sidewalks, and the thatched mats over which some people sleep. In most of them a square form predominates, as if she were trying to show how an orderly system of interrelating situations converge upon one another, whether they are family member sleeping shoulder to toe, market stalls all in a line, chromatically demarcated by the variety of their wares, or windows in an apartment complex with bedding hanging from each window. They drawings have the most in common with the wall reliefs though their use of forms and colors to achieve spatial and narrative events could also be easily misconstrued, for its possible that they are also maps of some sort, tracing memories away from the real. Just because we see a fence and a back yard in one drawing does not mean it is there. We could just as easily be looking at a code for the structure of an entire society, with each set of lines setting up a dynamic that is yet to be gleaned. But if we see shadows of intimacy here and there, that is enough.