The Actual Arranged, A Reliquary To Ruin, And Other Feats

The work of Andrea Burgay is densely layered and seeded with oblique clues to undisclosed meaning. It does not try to be beautiful, but imposes a sense of mystery that makes it wondrous. She makes what would ordinarily be called collage, but on her own terms. The word collage itself does not do her work justice unless it’s meant as a jumping off point into versions that not only expand the genre but our ability to perceive it. She’s been making these collages for most of her life, starting in high school and college; as a private cipher to any other discipline she was learning. If she was drawing something, then in her own time she would create a collage version of it. This has led to a lifelong fascination with the possibilities and the agency of form.

When I first saw her work in 2018, it left a strong impression. The works on display were small in scale but complex and oblique. They did not look small. They looked like keys to a larger body of work that would prove expansive and uncommon, and would defy normal expectations. That has been the case with looking at her work ever since. It’s very in touch with where it comes from, and how it is made, down to the molecular level of its arrangement, how holds it together. Burgay collects images and parts of images which transforms and sorts into groups of colors and random shapes. As they are used in each of her compositions, they aid her in accruing knowledge. Burgay works both small and large, thick and thin, and though there are rarely any blank areas in her collages, neither is there a crowding of elements. One can imagine treating her surface as if it were lain flat, with sections eroded or built up, resembling an excavation of a ruin, or an isolated landscape formed by nature’s touch alone, glimpsed for the very first time.

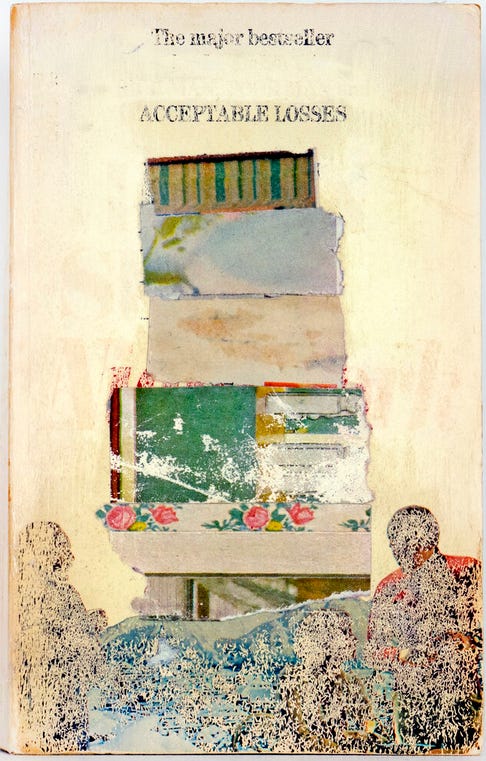

For her series FICTIONS, Burgay uses commercially printed paperback books and magazines as the support. Think of a book, any book you have read, or any run of the mill book you pass in a second-hand shop. It has something to say that requires a delving into the pages. These compact objects possess color and heft, previously printed surfaces, and are recognizable objects mined from mass media. They contain and embody layers of meaning. Even an empty book carries with it the possibility for future portent, as we may write or draw (or collage) into its large blank pages. Burgay fills her books with layers of matter that erupt from the surface like unseen minerals emerging with the shifting of tectonic plates. Burgay gives us a regeneration of form beyond theory or translation. She brings the layers of meaning to the surface so that we can engage with them freely. There they are, complex and ambiguous, massing into mounds of color and hand-torn form, not trying to establish any other relationship to meaning than what can be attained aesthetically. To attempt to reconcile any aspect of them with a finite statement would be the soul of folly.

Her series WISH YOU WERE HERE presents us with collages housed upon the very finite real estate of a picture postcard. They take a primary object or location that may generate impossible levels of nostalgia and transform it completely, covering it so that only the artwork exists under the blue skies and the backdrop of an endless sea or deep and mysterious jungle. Our most commonplace desire to be romanced by a fantastic locale out of travel dreams is replaced by another fantastic event, that of an artwork. In these the abstract elements are too small to do anything but meld together. In truth, the one association they suggest is of vintage monster films of the Fifties and Sixties, old black and white ones like “Them!” and “The Blob” and action monster films like “Godzilla vs. Gamera” and the early anime inspired cartoon series “G-Force”. In each of these films or shows, a new creature emerges into our world, changing it forever by adding something mysterious and transgressive to what is already known. Burgay understands the influence of such things. Her collages take the portent of creatures, forcing us to view the picturesque scenes of fantasy destinations in a more macabre light. If only the aesthetic moment uniquely available in each were accessible via plane, train, or automobile. Burgay makes the world, past and present, into a gallery of redolent meaning and terrible beauty.

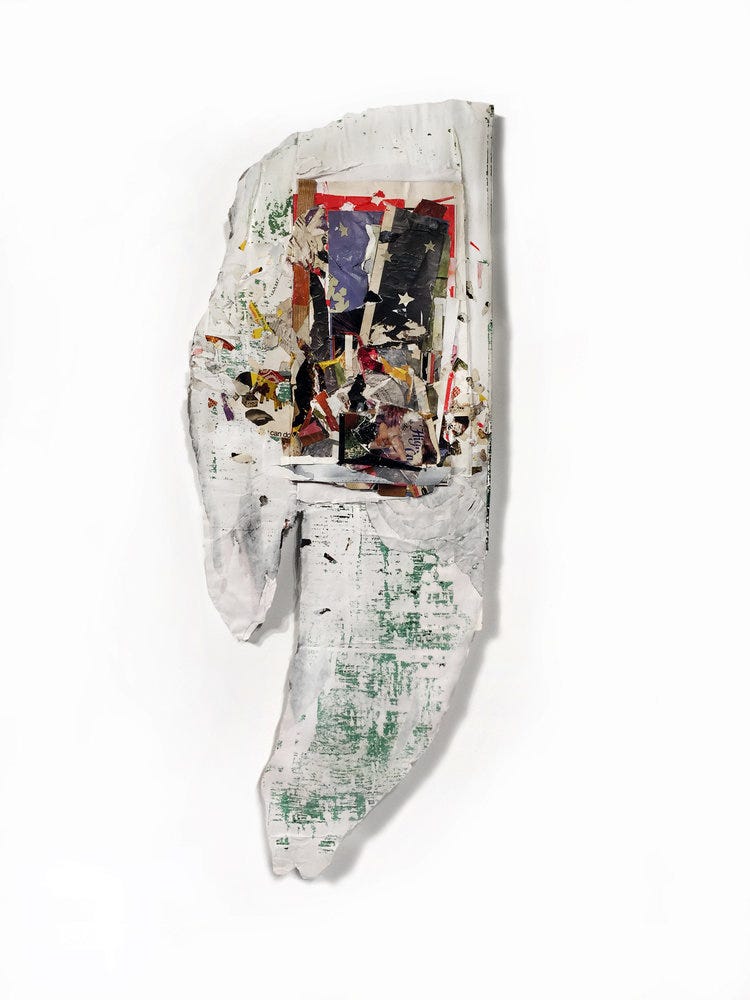

In Burgay’s NEIGHBORHOOD SERIES, there was a conscious effort to reclaim, and make something of a reliquary, albeit a ruinous one, of fragments from her neighborhood as she observed it being slowly lost to gentrification. She made a specific effort to retain printed imagery from street posters, very much in the vein of the Affichistes of Post-WWII Paris, artists like Jean Villeglé or Raymond Hains. Some areas are built up with sections that have been ripped and torn, showing a lot of whiteness emerging from a chiaroscuro of black or mustard yellow; in some cases the back of the poster with jagged edge and a torn lip hanging down is turned around to show only its wheat pasted back replete with layers of past posters creating a wall of white sound, and in the middle is placed a smaller collage of her own, on a small square area more specifically designed and lit with colorful backgrounding in relational hues. In these small models she almost seemed to be drawing an image of the real scene left behind, framed by the life-size fragment of the real object from which it was originally made. In this series the interior mode that usually generates her constructions has given way to a wild sampling from the raw outside life of the street. The vibrancy of the city is here, the heavy matter of forms and materials that originated elsewhere, that were not completely transformed by the artists, but linked to, mated with. What emerges is a totem or golem, a presence.

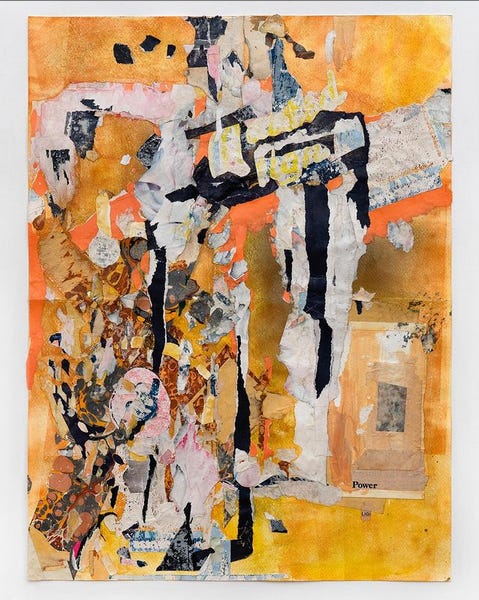

Burgay’s newest series is REQUIEMS, and they are her most accomplished and personal. By their scale alone they dwarf all her other works, except perhaps some that were partly three-dimensional and involved the negative space of the open wall to give presence to formal elements. They are all rectangular and measure on average 30 by 44 inches. Slightly larger than the average poster on a wall, but so much fuller in every way. Given this amount of space, Burgay is able to step back from the surface and play with interrelating parts, creating structures, energizing lines, scribbling in margins, planting a cue via a printed image that references something from her walled off private life and family history. There is something of a reliquary here, an ambiguity speciously contained; while all around it the provinces of ruin, of the passage of time, which lays waste to facts and emotions but leaves their marks as evidence. With more flat space than the coover of a book or of a postcard, Burgay is not forced to pile her chromatically selected fragments one atop the other, but can orchestrate a flow of painterly marks that lead the viewer from one territory of forms to another. When an image of a real thing appears it’s usually meant as a direct reference to something personal, or a clue to one, and the marks and forms that lead to and from them, or interrupt their connection to one another, depending upon your way of thinking, are meant to move the viewer around like choreography upon a stage. A requiem can be a reliquary but never a theorem. There are no exact messages, only layers of meaning meant to evoke meaning as visualized ambiguity. The power of the artist’s reality is translated idiosyncrasy that augers well for those open to it.

What is here and everywhere in Burgay’s work is a way of seeing what makes the world real, for in her dedication to historically bound disciplines that echo an intimate relationship with a specific creative genre, she allows us to share how she occupies a space of her own making. These works are creatively realized snapshots of how she specifically lives in the world, how she occupies the portion of space allotted to her. They contain all her hopes and dreams, her fears and her memories. Her actual self, arranged.