THE BOOK OF BROTHERS

CALIFORNIA LOCOS : RENAISSANCE AND REBELLION. Edited by Dave Tourjé with texts by Shana Nys Dambrot, Michelle Deziel-Hernandez, Chaz Bojórquez and Lauren Over. Intro and Forward by Paulo Von Vacano and Dave Tourjé. Art direction by Nano Nobrega. Published in Rome, Italy: Drago Publisher, 2023. Hardcover with slipcase, 432 pages, with numerous color photographs.

America is a broad expanse filled with cultural melting pots as varied as they are unique. Though it may be difficult to judge scenes as diverse as they are geographically alienated from one another, the view from inside can prove affecting and even transformative. California Locos: Renaissance And Rebellion is a new book about a scene reflective of multiple generations and communities in greater Los Angeles, one that is associated with and generated by five specific individuals, creative personas each of them, tangentially related from more than one direction, among friendships and a shared desire to own the cultural force that motivates them. The California Locos are a band of brothers whose cultural imprimatur is beyond reproach, and who each bring a standard of expression, feeling, and sensitivity to the hybrid texture of Angeleno life.

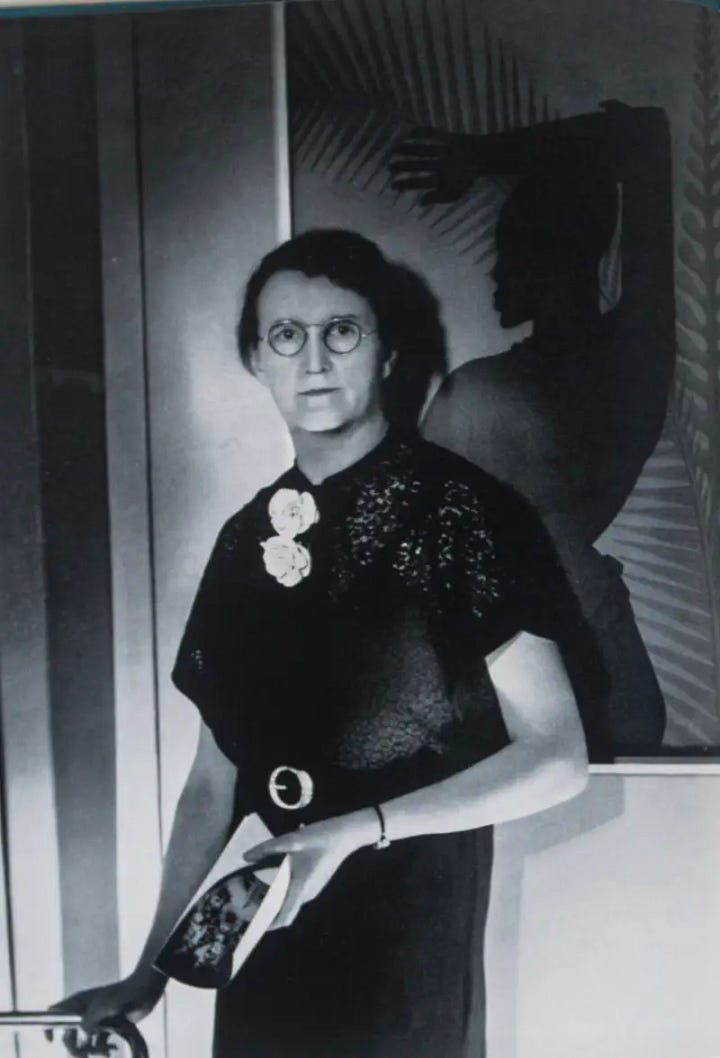

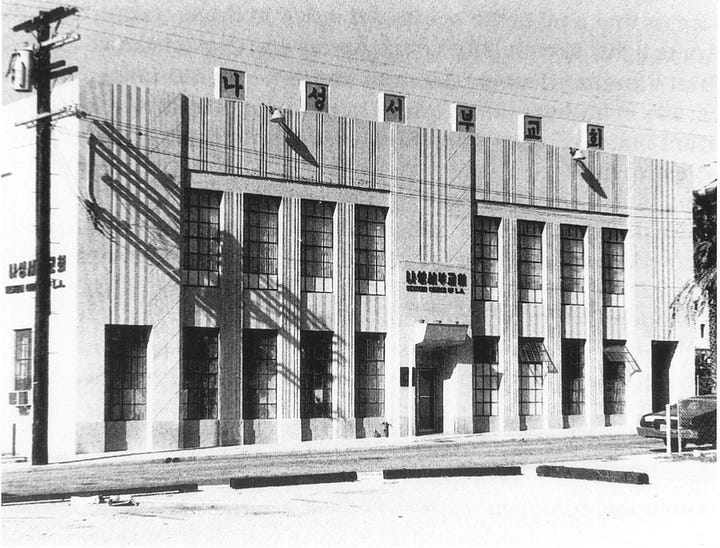

These five individuals are Chaz Bojórquez, Dave Tourjé, John Van Hamersveld, Norton Wisdom, and Gary Wong. Of the five of them, four attended an important cutting-edge LA art school called the Chouinard Art Institute, where each cut their wings, so to speak, and had early formative experiences that laid the groundwork for their future evolution as artists with all related accomplishments. In a way, Chouinard led them back to each other, and it was the propitious event of Dave Tourjé, himself the only non-graduate from the same school, who bought and restored the 1907 home of Chouinard Art Institute founder Nelbert Chouinard. What each learned there helped focus their innate abilities and led them to make certain choices, and take certain chances, into the diverse worlds each has made their own. Tourjé’s realization that the property he had bought had special historical significance for Los Angeles’ culture led him to establish the Chouinard Foundation, and it was in this watershed moment that Tourjé began to invite Chouinard artists including Bojórquez, Van Hamersveld, Wisdom, and Wong to discuss reviving its legacy.

The culture of Los Angeles is dynamic, diverse, and completely divorced from the Eurocentric ideology that informs East Coast living. It’s a completely different kind of urban center, one shaped by an openness verging on entropy, where multiple scenes interact, creating partially merged territories, and where there is no exact center. Borders exist to generate alienation and conflict. Within the territory known as Los Angeles there are many neighborhoods, organically stacked one atop the other, sharing among them a strong working-class ethic. The elements at work in the shaping of artistic vision are different here than in other places. Artists both gather and cohere in areas where they can meet and live together. The land itself dictates this. Most urban centers began as ports, and then a city grew, over decades and centuries, displacing the industries so that landed classes could dominate choice areas of what later became known as “real estate.” Cities like New York, Boston, and San Francisco all followed this same trajectory. Founders established ancestral lands that became historically important areas and pushed the working class further from business centers. Rivers and bays created natural boundaries that separated prime real estate from less desirable areas, which counted as just “everything else.” But Los Angeles was different. Los Angeles has had a cumulative history. It is essentially a pioneer town, the last one that could possibly develop, and one that retains its spirit of inclusiveness, of mutuality, with the luxury enclaves cutting miniature swaths across its greater area. It never really cultivated a city center but expanded in all directions from a very basic hub.

There has been considerable art history associated with the LA scene which needs mentioning. The details that are most pertinent have to do with Nelbert Chouinard and the Chouinard Art Institute, established in 1921, and kept afloat with the help of Walt Disney, whose first generation of illustrators received their formal training at Chouinard, raising the bar for his famous cartoon figures. Disney endowed the school to the tune of 10 million dollars in 1955, so it was open in the mid to late Sixties when the various members of the Locos began to attend classes there. Many of them attended classes on scholarship, which is to say they were granted generous permission to attend classes at will, with no conditional authority being applied. Being trained at Pratt in NY, her school followed progressive principles in line with the philosophy of John Dewey and brought important artists like Hans Hoffmann, David Alfaro Siqueiros and others to teach there. Many artists affiliated with the Abstract Expressionist group from New York later ended up teaching there as well, such as Emerson Woelffer, Matsumi Kanemitsu, and John Altoon (who exhibited at the seminal Ferus Gallery with other Chouinard artists such as Larry Bell, Llyn Foulkes, Robert Irwin, Ed Ruscha and others). All the Locos, with the exception of Tourjé, studied at Chouinard and this connection was instrumental in bringing them together years later. The fact is, they were all living and working beside one another without any direct collaboration for years; they were each simultaneously building their visions and disciplines and they sort of fell into one another’s lives through happy accidents and other workaday involvement where they chanced to meet. Tourjé and Wong briefly met in 1980 because Wong worked for an art moving and installation company called Cooke’s Crating that was delivering art to a Los Angeles Bank called Security Pacific, which possessed a major contemporary art collection, and Tourjé worked as the receiving manager for the curator of the collection; subsequently, this collection also owned and exhibited works by many other Chouinard graduates. So, this is how they both met. Tourjé knew of Bojórquez from his graffiti tags and local murals, but only met him officially during those early meetings to sketch out a visionary plan for the Chouinard Foundation. Tourjé had been bumping into Norton Wisdom in the LA Punk scene when Tourjé also made the rounds in bands like The Dissidents where they were both performing at local venues like The Cathay de Grande, Club 88, Club Lingerie, and others. Wong and Van Hamersveld knew each other from their Chouinard days. Gary had worked with John as the MC and acts booker for Pinnacle Dance Events at The Shrine Auditorium. The story of the Locos is connected intimately to Chouinard and to the culture of the LA scene which, in its diversity and complexity, held many creative lives in the same interspersed communities from which each of them sprang.

Gary Wong’s creative accomplishments are diverse and have alternated in his active practice between Abstract Expressionism, mixed media, and word paintings. His work mines the depiction of ethnic, spiritual, and cultural figures—each work a model for divergent paradigms that exist simultaneously in a representative reality; alternately, he makes paintings and murals that enact the fragile contexts by which language defines identity, placing words in a visual context that reveals their tendency toward oblique and obscure meaning. These works embody his specific condition of dealing with dyslexia as well as his complex ethnic character, which originates from a completely non-white, non-mainstream cultural self-identification. Wong’s work swings back and forth between bases in theoretical and reactionary contexts—the cerebral versus the emotional and ideological, responding either to reply felt and implicit meanings that are the product of intellectual thought, or responses to the living environment around him, stretching from local communities to world events and issues. Wong identifies with marginalized communities that disparage official culture wherever it is found.

Chaz Bojórquez also grew up in Highland Park and studied at Chouinard but came there late and was not quite finished with his degree when the school was folded into CalArts. Unable to find the right place to make up the necessary credits in Ceramics, which at the time was his chosen discipline, he ended up turning to the language of the streets, the vernacular of community and gang life that was and is graffiti and found unique ways to make it his own. Early examples of his work, called Cholo-style, are now in the collection of The Smithsonian American Art Collection. These two major works, “Placa/Roll Call” (1980) and “Somos La Luz/We Are The Light” (1992) both depict a wall long and high list of names, respected members of the graffiti community, drawn in a calligraphic style that resembles the lettering used in historically established legal documents, like those used to announce the establishment of laws, deaths, and other official matters. Bojórquez is dedicated and disciplined, and his works achieve a masterful grace that has evolved the practice of graffiti as cultural expression, putting Cholo-style on the map.

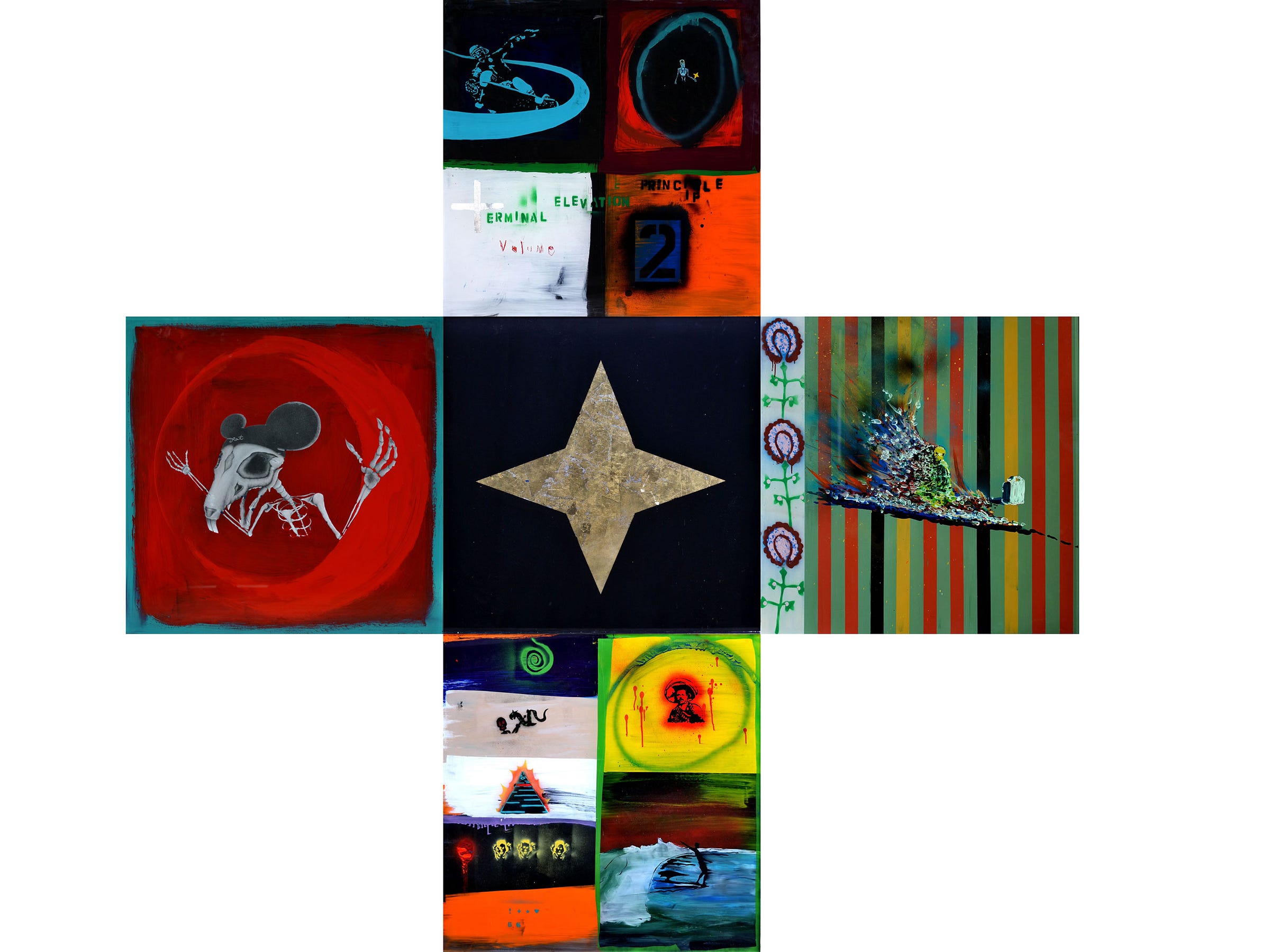

Dave Tourjé is the youngest of the group, he is the author and editor of this book, and has also produced films about the Locos. Tourjé has become part ringmaster on operations regarding the legacy of the Locos altogether, as he likewise organized the Chouinard Foundation, which continues to honor the legacy of the Chouinard Art Institute. The Chouinard Foundation started a brick-and-mortar school in 2002 which morphed into a partnership with the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks to bring the program into underserved inner-city areas by sponsoring the efforts of young creatives who would benefit from direct contact with the Locos themselves. This ended around 2009 in the economic crash of the day. In 2015 he was executive producer on the documentary film Curly which explored the history and legacy of Nelbert Chouinard and the Chouinard Art Institute. Containing interviews with storied graduates and one-time teachers it also delved deeply into the lives and art practices of the Locos and tells the story of a young graffiti artist sponsored by the Chouinard Foundation, his own life and aspirations. After this, the Locos produced events at the LA Art Show with “Chouinard: 100 Years” and the “Chouinard / Siqueiros” events in 2020 and ‘21. They still keep things alive on social media with the combined Chouinard Chronicles. Tourjé is an established artist who was having solo exhibitions at museums twenty years ago. His art is heavily influenced by the Finish Fetish school from which other artists like Larry Bell, Joe Goode, and John McCracken practiced. “Artwork of this type often has a glossy and slick finish and features an abstract design on a two or three-dimensional surface made from fiberglass or resins. The style is similar to the simplicity and abstraction of minimalism and the bright colors and reference to commercial products found in pop art.” [Atkins, Robert (2013-11-26). ArtSpeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present (3rd ed.). Abbeville Press.]. Tourjé uses a process called “Reverse-Painting'' in which one applies paint to a piece of glass and then views the image by turning the glass over and looking through the glass at the image. This gives the work a sheen and the illusion of transparency that are alternately slick and cerebral. His painted works are consistently impressive, measuring on average either five by six feet or nine by nine feet, they use a cross like form that gives one the impression that they are markers in the passage of time, cenotaphs on a road with a destination unknown; they are symbols of transformation. Their structure is inspired by travels Tourjé has made across the country, where he saw antique quilts fabricated out of whatever was available–cultural expression as a form of survival, American ethos of poverty and resilience. This has likewise been the attitude of many West Coast artists like Wallace Berman and Ed Kienholz, using the detritus of industrial waste and making it culturally memorable. What makes Tourjé’s works unique are his injections of surf/skate culture, rock and roll, comic books, which inhabit backgrounds that are Pop in the extreme. They emerge from the iconography of youth cultures that permeated Tourjé’s early years and continued to prove engaging: surf, skate, and punk cultures, a love for hotrods, and the art of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Robert Williams, and MAD Magazine. Tourjé was also the product of a multicultural upbringing, having spent formative years living in Mexico City with his mother, where he discovered the muralism of Siqueiros and Rivera.

Norton Wisdom attended Chouinard at a very young age—he was only fourteen, which meant he could only attend every week on Saturday, as during the weekdays he was attending Beverly Hills High School. Wisdom’s experiences led him to break with the established authority of classes and further down the line, when he was actively exhibiting, he was sickened by the glib careerism of his artistic peers. He decided then to drop out of the gallery game. He destroyed much of his then current work and began a practice of performing live paintings in tandem with live music performances; after each event, the works are documented and subsequently destroyed. Yet the documentations are archived and used to make collage works that exist as both second generation works, unique in and of themselves, while also serving as an homage to past inspiration. Few examples of his work overtime still exist, the exceptions being those donated to charity or sold at auction for similar benefit. The mortality of his work in progress lends a mythical quality to their very making, and proffers upon the artist himself an authority to speak on subjects that affect his creativity, including world events and social issues of strong moral importance. Robert Berman, of the Berman Gallery, calls Wisdom an artist’s artist whose work is, “strong…and from the heart.”

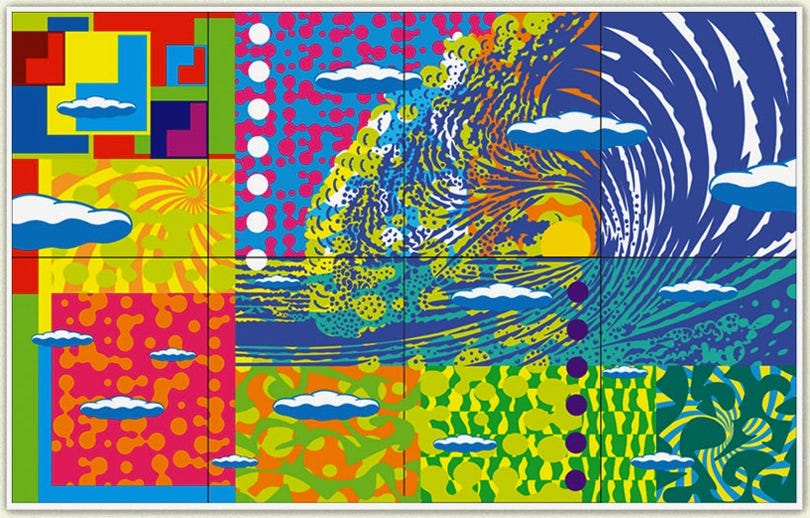

John Van Hamersveld is best known as the artist who has designed for everything from rock posters and album covers to Hollywood and mall culture, which are visibly famous, though few may actually know it’s his name behind them. His best-known images include the pop poster Endless Summer about young men surfing on endlessly sunny, white-sand beaches promoting the California lifestyle and the surf life that is completely merged with the popular image of California itself. His artwork has also graced the covers of famous album covers by The Beatles (Magical Mystery Tour), The Rolling Stones (Exile on Main Street), KISS (Hotter Than Hell) and Blondie (Eat To The Beat) and hundreds of others. His involvement with the culture associated with music also extended into establishing Pinnacle Dance Concerts, the forerunner of modern concert promotions, a permanent series of events hosted at the Shrine Auditorium in Downtown Los Angeles that included the major bands of the late ‘60s. Yet it’s his artful designs that survive as his main legacy, he’s even been given the honor of gracing The DWP tank on Grand Avenue in El Segundo, CA with a major mural–a 500 foot long permanent cultural imprint on the cultural sphere of the city itself.

RENAISSANCE AND REBELLION is in part a calling card for the Locos, as their combined works and reputations participate in a European Museum Tour beginning in Rome in 2025. It’s many things all at once. It’s a time capsule, a scrapbook, and a historical document to the accomplishments and figures who have each in their own way epitomized LA culture. Without Tourjé the California Locos would not exist. They would have continued each in their own way, but the collision of visions that he has helped to achieve would not have been possible. The cultural ambitions they share, and inform, both to one another and to the greater society in which they live and make their art, would not be conscious of their cumulative portent. As the renaissance continues, it shows how rebellion makes the world a better place.