At this point, we find Nolan Preece at forty-four years of age, facing some daunting changes in his recent professional life that for anyone else would represent an insurmountable alteration in the fabric of their self-expectations. But it’s the timbre of Preece’s character that he is endlessly hopeful, is involved in several adventitious circumstances at once, and despite all his challenges, he never looks back or gets embroiled in thoughts that would impede the progressive nature of his own intelligence. 2001 presents Preece with some choices to make. He’s decided to close his gallery, Sun Mountain Artworks, where in the space of six years he has curated some 50+ exhibitions of artists of the local and regional area, giving opportunities not only to budding artists and local curators, but to community organizations like The Comstock Arts Council, Saint Mary’s Art Center, and The Northern Nevada Correctional Center in Carson City. These exhibitions represented a cornucopia of artistic expression, and to have been responsible for housing them together, independently, under one roof, must have made Preece very proud. The reason he gave up the gallery was because in order to keep offering more opportunities at an advanced level, would require an investment in new technical equipment, the same equipment that he used to offer private classes in photography and printmaking, and for his own use as well. With so much riding on the space being maintained as a viable production and exhibition center, it seemed at the time to put him at an impasse. The timeliness of this decision was more portentous than he could have imagined, for with the occurrence of 9/11, there was a sizable downturn in local tourism, which affected attendance of the gallery, as well as also affecting the sort of funding their cultural affiliates relied upon to sponsor and mount the exhibitions they did with Preece. Such opportunities became scarce and the willingness to embark upon them considerably less feasible. Closing Sun Mountain Artworks was the only choice left.

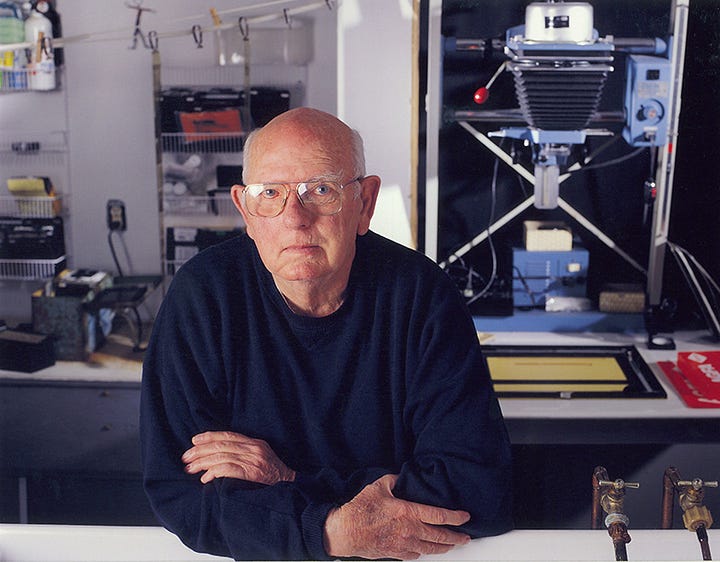

In a time that would usually be filled with anxiety and indecision, Preece was feeling exactly the opposite. He was now able to devote himself solely to his own creative work. He was excited to finish some long standing projects, such as the cliché-verre work he had pioneered during his MFA years. It was his intention to expand the portfolio he already had and give it more notoriety. This resulted in the creation of thirty more 16 x 20 inch silver gelatin prints, split toned with selenium, numbered and signed. Preece admits that it had been so long since his last period of involvement with this series that he had nearly forgotten the procedures required to attain the qualities in them he most espoused. Following this new edition, he garnered an award that created a situation of advantageous circumstances. The prestigious The prestigious Rosemary McMillan Award for Excellence In and Service to the Arts was presented to him by the Sierra Arts Foundation, an important organization that supports the arts in his area. This award was the first of a series of awards and exhibitions that resulted in newfound opportunities and life changes for Preece.

In 2001, a set of unforeseen circumstances led Preece into a continuum of chance encounters that provided immense opportunities for his artistic career. Through the involvement of certain luminaries in the photographic community, Preece was able to expand his connection to the lives and models of other established photographic artists. The first of these opportunities allowed him to re-enter the educational profession. That year, he was contacted by Truckee Meadows Community College, asking him to take over some of the classes for his friend Erik Lauritzen, whose lifelong affliction of kidney disease was beginning to overwhelm him. Preece’s return to teaching in 2001 coincided with a major change in the technology of photography. It was the advent of digital photography which, after an initial phase of resistance, Preece decided he did enjoy. Lauritzen heartily approved of the new technology, and it injected a new spirit of discovery, and a required professionalization of the procedures mandated to raise the simple aperture based photography both for themselves and their students. As he told Preece, “if the train is leaving the station, we’d better be on board.” Together they took the idea for both beginner and advanced classes in Digital Photography to the curriculum committee. Preece states with pride “I wrote the first syllabi and taught the first classes in digital photography at Truckee Meadows Community College. In my first class I had one G4 tower computer that I borrowed from Graphic Communications, one small printer and five students showed up with 4MP point and shoot digital cameras. We were off and running and we beat the University of Nevada, Reno to win a digital photography program. I also needed these classes for the position opening at TMCC to teach three photo classes and to run three galleries on campus in 2003. I bought my first high end digital camera, a Canon 10D just for good measure.” Preece’s involvement with the TMCC Gallery, was making great strides. He decided that in order for it to progress at the rate he hoped for it, the potential exhibitions, and therefore the greater audience for it, needed to be national. He placed advertisements in San Francisco’s Artweek magazine and several other art related publications, and the solicitations poured in. Most were college professors going for tenure, which ensured high quality exhibitions for his time at the gallery’s helm. Among those exhibited were Bob Morrison, a conceptual artist teaching at The University of Nevada in Reno; David Olivant, a painter teaching at California State University Stanislaus; Jan Pietrzak, a platinum printer; Alan Weber, emeritus of Ansel Adams’ Friends of Photography, Thomas Turman, a sculptor; Kelsie Terry Harder, TMCC ceramics professor; Erik Lauritzen, TMCC photography professor, Gerald Franzen, a photographer; Cynthia Delaney, a photography instructor from Elko, Nevada; Phyllis Shafer, an instructor from Lake Tahoe Community College, and many others.

Returning to focus his creative interest upon the chemigrams in 2005, Preece experiences a mental block on the process he had invented, due to having only been doing intaglio printmaking in recent years as part of his teaching efforts at Sun Mountain Artworks. He began again by starting what he calls Simple Solutions—-sheets of regular copy paper soaked in Dektol developer and then dropped them upon 16 x 20 inch sheets of photo paper. This creates a stained frame around the blackened image using thiourea and sodium hydroxide, compounds that bind well with elements such as Au and Ag (gold and silver). He then gold toned the entire sheet. This experiment proved fruitful, so he used it for the next project called “Simple Systems”. He borrowed the title from Douglas Huebler who called conceptual art “simple dumb-bell systems.” Preece elided the title of its “dumb-bell” connotation and had the name he could use for his new project. This involved taking 20 x 30 inch Fuji Crystal Archive color photo paper and placing objects on the photo paper in total darkness. “Line, square, rectangle and circle were the elements of art I simulated using spaghetti, Post Its, xerox paper, and enlarger condensers. By exaggerating the color in the enlarger head I was able to create bright colors to make the simplicity more palatable.” It was with this series that Preece won the Nevada Arts Council Visual Art Fellowship Award by 2007. In the artist’s statement me provided for the application, he writes:

“Throughout the years I have been on a personal journey into invention with chemistry and a search for the aesthetic in experimental photography. Photographers try to capture what they see and feel, but at times only out of spontaneity and a series of small serendipities is the path ahead made clear. Photography lends itself to producing a multiplicity of effects difficult to obtain otherwise. It can be the most direct means of self-expression within time limitations, since the image can rapidly be produced once a concept is in mind. Although process and concept in a photograph have an integral relationship and there is a delicate balance between the two, it is easy to overwhelm the concept with technical prowess thus making process the subject of the work. Experimentation is everything to photography, both conceptually and technically. I try to bring attention to topics such as climate change, the oil industry, chemical effects on the environment, and social behavior. I bring realism into play through the effective infusion of photographs, fragments juxtaposed with chemical effects. This method of working can create whimsical, yet sarcastic images that at times may appear inappropriate or unconventional.”

2007 was a propitious year, one that offered grand opportunities while also seeing the loss of a good friend and colleague to illness. The high point of the year at TMCC was when he offered Albert (“Al”) Weber a career retrospective at the TMCC Main Gallery. He was seventy-seven years old and had quite a career behind him. The exhibition featured works culled specifically from what Weber called his “commercial work”—photographic assignments to cover subjects such as coal miners.

Preece offered Al Weber a career retrospective, which ran for six weeks in June and July of 2007. Preece recounts that “ He was glad to get the invite because he was usually looking out for someone else and hadn’t considered he might need an exhibition.” It was very well attended and received a spirited write up by Anthony Mournian for The Photographer’s Formulary newsletter. It was unique in that it featured not only his Western landscapes but also several works that showed how he used photography as the “meat to make a living.” These included a series of portraits of Miners in Sunnyside, Utah that he did for the Kaiser Coal Company. His images humanized them and showed the real environments in which they worked, in all its ruggedness and stark detail. He also exhibited images he took in Finland for Architecture magazine. He liked the Finns and their country so much that he stayed there for three years and found all manner of projects to keep him busy while there. After Weber’s show ended, Preece accompanied him down to Las Cruces. The Las Cruces Art Museum was presenting an exhibition Schranz had organized on Adams’ work along with his closest associates. Weber was going to speak, and the auditorium filled up to the 250 maximum. He gave a wonderful talk about the little things he knew about Ansel, the things between friends. At the end of his talk, a woman announced that there were 250 more people outside that would not be able to hear him. Al [Weber] stood up and in a loud voice said, “Send them on in, I’ll do the talk again.” This was the kind of person Al [Weber] was.

Meeting Paul Schranz, the museum director and the senior editor of Photo Techniques magazine, was important to Preece’s career. Schranz was in fact hosting them at his home for the lecture. Schranz would connect Preece to a greater community around the concept of the Chemigram. Schranz invited Preece to contribute articles to Photo Techniques on three different occasions. The first was in the November/December issue of 2010, it was called “Grams, Grams Chemograms and Nolangrams” and constituted a discussion about methodology, philosophy and concept of his work, including a portfolio of the works themselves. This article led to his contact with the Belgium-based Pierre Cordier, described as the “father of the chemigram” and this connection led to many further opportunities. Other articles for Photo Techniques included the July/Aug issue of 2012 with “A Call to Photograph: Erik Lauritzen.” about the life and photographic work of Erik Lauritzen, and the Nov/Dec issue of 2013 that featured “In From the Light” about a darkrooms documentary project started in 2009 with Al Weber. Following an extended correspondence with Cordier, he invited Preece to attend his solo exhibition in New York in 2013 at the Von Lintel Gallery. Another local practitioner, Douglas Collin, who taught chemigrams at The Manhattan Graphics Center facilitated a Chemigram Summit and ten ‘chemigrammists’ all met under one roof for the first time.

Weber also expanded Preece’s creative community. He was so appreciative of the retrospective Preece had given him, and for accompanying him to New Mexico, that honored him with a party to meet all his West Coast photography friends. Kim and Gina Weston, Ted Orland, Will Giles, Richard Garrod, Henry Gilpin, and Barbara and Fernando Batista, were all in attendance. This party was held on August 9, 2007. Al told him he was “one hell of a photographer.” Later they teamed up to make a book about darkrooms, called In From The Light, because many were being lost.

In August of 2007, Preece’s friend Erik Lauritzen died at the age of fifty-four, succumbing to a lifelong debilitation due to kidney disease. There comes a time when the inequities of the body, combined with age, simply give way to any major health issue. It was a sad time for their entire community. Laurizten was the one who actually established the Photography department at TMCC in 1991, and taught in it for thirteen years; he also managed the on campus art galleries from 1991 to 1998. A workshop assistant to both Ansel Adams and Al Weber among others, he was highly exhibited and published in his lifetime. He was honored with a memorial exhibition in the Spring of 2008 at The Nevada Museum of Art.

In 2009 Preece had just purchased his second high end digital camera, a Canon 5D, Mark II. One of his old students told Preece he was a vet and upon comparing notes they realized he had been in tanks in the Army and stationed at the same place Preece had been stationed. He also said he could fly an airplane. Preece immediately asked him to take him up. Destination, the Black Rock Desert north of Reno. Preece had done much photography from airplanes and helicopters during his work for the environmental companies. Preece recounts that “It had all been with film and was a real pain to try to load film in the heat of the moment. This digital camera was a miracle. I could shoot with very fast shutter speeds; I could delete at any time, and it was versatile. All I had to do was open the window and fire away. Two flights to the Black Rock and one along the Carson Range near Reno netted some very handsome photographs. This experience would finally culminate in a flight over the Bravo Bombing Ranges in 2013.”

I was asked to present a huge cliché-verre piece for Burning Man in September, 2009. I made the image and tried to prepare it for the beating it would take from the sun and the wind. It was successful and we who were in the collaboration were given a one-day pass into the workings of this large gathering on the Black Rock Playa. I took the 4x5 along and managed to take a nice image of “The Man.” There was so much I still wanted to photograph in Nevada. I started thinking about a sabbatical for 2010.

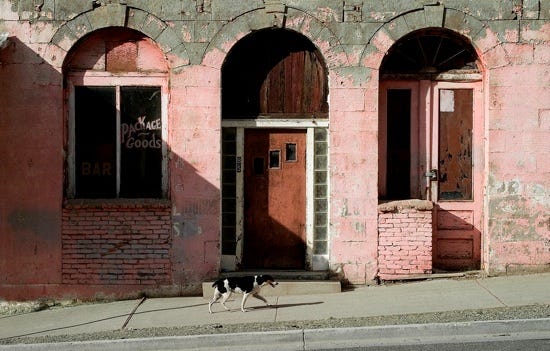

In 2010, Preece was granted a year’s sabbatical. In that time, two books would be made, one called Great Basin Patina and the other titled The Nevada Landscape. Preece held a longtime bias against photographs that depict interesting beauty and are successfully made. This was his aim, and it fueled his interest in achieving new creative aims while traveling around his home state. Digital and large format cameras would be his tools. Part of the time he was on my own and part with Jeanne at her plots. Preece finished the books on deadline and started to prepare for his next year of teaching. Suddenly the phone rang, and it was the college president offering him a buyout. Preece was in anguish for a couple of days, but Jeanne was all in favor of his taking it. Preece’s college teaching days were over and a whole new decade was beginning. He had accomplished two books, a trip to Scotland, and three photographic airplane flights over northern Nevada.

Upon regrouping, Preece started to chart a course for the rest of his life. He wanted to jump back into chemigrams. I had briefly read Pierre Cordier’s website about chemigrams and realized he was working with resists to the chemistry and I had been working with painting with the chemistry. I remember clearly that on September 1, 2011 after trying some experiments with Pierre’s technique using polyurethane, I reached for a bottle of Future Floor Finish. We had been using Future in my workshops to ground our copper plates for etching them in ferric chloride. It was a much less toxic way of working without breathing the fumes of mineral spirits used to clean petroleum based hard grounds from the plate. A small amount of Ajax was all that was needed to clean the Future from the plate. Future Floor Finish was acrylic based and easily cleaned with alkaline based cleaners. I dribbled some Future on a sheet of silver-based photo paper and made some stripes through it with a rubber brush. It would need to dry and in Nevada that is very quickly. I then placed the photo paper in the developer tray I had made for working that day and I couldn’t believe my eyes. The developer was not only seeping in along the edges of the Future, but it was creating all kinds of textures as it was breaking down the center regions of the Future. The photo developer’s alkalinity was working for me. I quickly rinsed the sheet and placed it in the fixer tray. Again, the fixer used the entry ways created by the developer and started to brighten the image everywhere the developer had entered and had changed the silver halides to black metallic silver. Developer is a reducing agent of silver halides changing the halides into black metallic silver or gradations of gray. Fixer is a solvent of silver halides removing it from the paper and when mixed with developer there is a combination that creates the illusion of many different shapes and textures on the paper. For my own purposes, I had discovered a whole new medium. Jeanne didn’t see him for a couple of days. He was immersed in his lab playing with a new toy. He tried all the varieties of photo papers on hand. He tried going into the fixer first with much different results despite more often than not they were all successful. It seemed that Kodak Ektalure paper with a G surface gave the best results. The surface of the photo paper had something to do with successful images. It was difficult to create a one-of-a-kind piece without any imperfections. The original piece would need to be scanned in and cleaned up with Photoshop. Preece started to experiment with ideas about the environment because this new process offered a foreign setting in which to place objects. As Preece says: “Occasionally the process delivered a “performance” print that could stand on its own, but usually the prints were the “score” for a much better version of an idea.”

During a trip with his wife Jeanne for a climate change conference in Fairbanks, Alaska, during which Preece took some great photographs among the serene beauty of the northernmost country, he happened to receive an interesting email from NYC. It was from Douglas Collins inquiring if he had a show anywhere or planned to have one soon. Preece noticed his area code was 646 somehow knew that it was in Manhattan, and that perhaps he should talk to this guy. They started communicating by email. Douglas was teaching chemigrams at the Manhattan Graphics Center and he told me that he and his students had been looking at my website for months wondering how this guy living out in the Nevada desert could be making such interesting prints. Preece recalled that his website had received an amazing 70,000 hits over the past year. Douglas explained that Pierre Cordier wanted to talk to him about the labeling of his prints as “chemograms” and that he should contact him. When he and Jeanne returned to Reno, Preece really wanted to be in contact with him. He waited for a few weeks and finally emailed him. Cordier explained that he had named the “chemigram” back in 1956 when he had his show at the MoMA and that I should be calling it chemigram. Prece recalls that “I thought for a moment and decided that politically I should change. I didn’t particularly like the “chemo” connotation of the word so I said I would defer to him and change the name, although I didn’t tell him about my new process. We were like friends from then on.”

So ends this part of Nolan Preece’s story. Many changes are afoot. New experiences abound. His creative work deepens and his access to travel and personal experiences expands his heart and mind. Friends pass, and new friends are made. Preece realizes the texture of his career to come will be involved with the Chemigrams, and he meets other important practitioners, and even the originator of the form, who welcome and celebrate him. Looking to another chapter, we stop and reflect with the joy and inspiration his art and life have so far given us.