The role of the artist is too often dictated by the tastes of art dealers and collectors, people who are in no way connected directly to the actual making of art, though they do in their own way support and advocate for it. This state of affairs leaves the artist at a crossroads as to what subjects they should address and what styles or disciplines they should employ to achieve a statement of enough originality that it passes through the threshold manifested by autocracies of taste and power. It's up to the artist to proceed through a series of choices toward, though, and into a subject worthy of their discipline and their vision. For the Spanish painter Joseba Eskubi, this has come to mean an extended body of work that transforms normal perceptions into a dream-state similar to that of the Surrealists and the late-Renaissance macabre masters Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymous Bosch. It is surreal to a radical degree and produces pictorially radical and aesthetically indifferent images that are beautiful because they are grotesque.

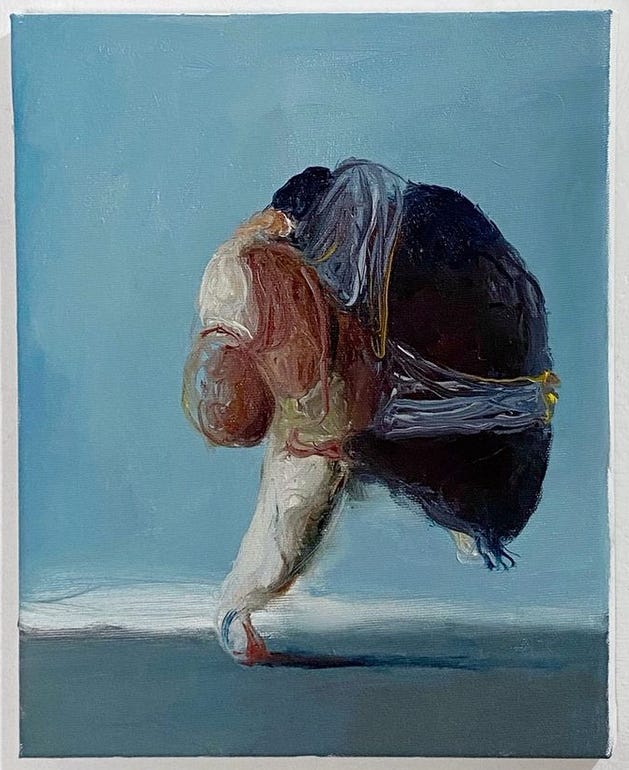

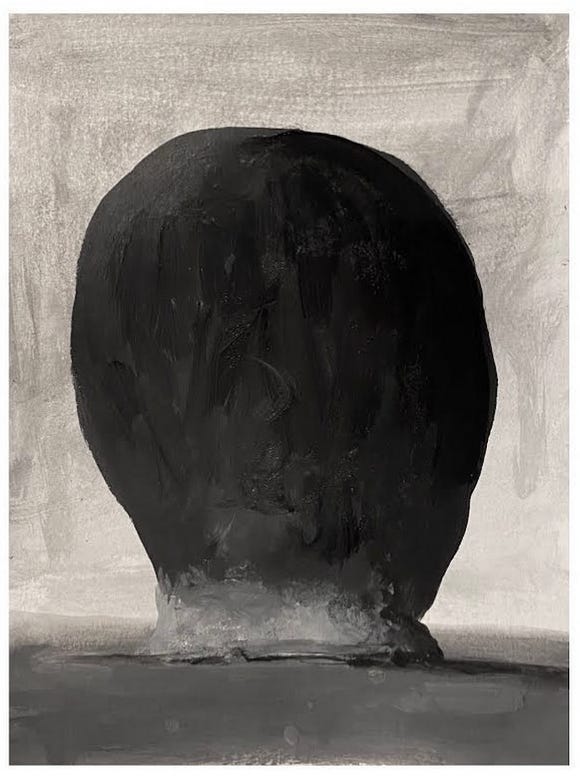

If you spend some time with Eskubi’s paintings, your first reaction may fall in the range of incredulousness. What are these paintings, you may ask? Their subject is a range of forms, inhabiting mysterious dimensions, that are not seemingly human in any discernible fashion, though they seem to be enacting a range of actions or states of being that are mythical or at least allegorical. They could be construed to be scenes out of a grander narrative in which the same moments, whether as acts of individual agency or as auguries of suggested meaning, lend a texture and depth to their perception. The body issues that animate Eskubi’s work confront the historical concept of the Grotesque, which is posited as the opposite of Classical beauty. It takes its influence from darkness rather than illumination, from sexual passion rather than idealized bodies originating in Classical antiquity—which were in themselves a mode of hiding passions of men for men. Myth or history realized pictorially has often served to obscure the darker passions of humankind. The use of the grotesque is, in this regard, the more honest of the two options, as it presents the unadorned bent of a degraded nature without the trappings of epic tales in which to clothe it. A grotesque figure in and of itself has a specific type of truth to tell, and though it is not traditionally beautiful, it may deliver a potent example of both character and agency. The difficulty is not in the figure as presented, but in the system of comparison that raises the Beautiful and lowers the Grotesque. These are just different kinds of shadows. In Eskubi’s perspective the field is leveled, so that not only can they each be judged equally, but they are actually merged into a sort of ‘beautiful grotesque’.

Eskubi’s paintings are a kind of abstraction in which pose and gesture take over after details are obscured or erased. His paintings accentuate the degree of obscurement to make unreal scenes abundantly sensual. Eskubi is fascinated with a certain fleshiness, and in oblique gestures or views of body parts like hands or heads. Looking at one of these images, we imagine them in say, a photograph, and then we begin to understand that Eskubi wishes to steal back the significance of the gesture from the photograph, and to return a certain erotism to the painting, paired with an oblique, possibly eerie nomenclature. His hands are bereft of a body, yet they become symbols of presence, and therefore of agency. We can even find them beautiful. They are like little birds flitting about. It’s in fact easier to imagine them as anything else but hands, unless they are the only visible enjoinder of some hidden spirit, an angel or a ghost, who wishes to project some palpable presence into the events of everyday life. The forms which Eskubi presents are like bespangled lumps of viscera, dressed-up versions of whatever it was that first clawed its way out of primordial swamps to eventually become something resembling a functional living creature, and finally, at the end of a long evolutionary ladder, a human being. They are alienated clues to our origin from the clay of being. They remind us of how far we have become without even knowing what it truly means to be alive.

Eskubi’s paintings are both eerie and magical and yet also intrinsically human. They reduce dimensions of a universal humanness to symbols that are like reflections—echoes in a continuum of symbolically resistant forms. The reflections that are abundantly present in his paintings are of the spirit of historical depiction, and the drama inherent in narratives that have access to archetypal prologues. Each is a moment distilled from the overarching story of human history. That they resemble the reflections of the past is enough. Cumulatively though, they are different enough that their esthetic resistance creates a radical context for new meaning. The parable of the painter is similar to the writer of epic poems. Though Eskubi creates one image at a time, he creates a world into which we may project our own lives.

Beautiful grotesque! Astute and informative. Love the work too.

Excellent.