Appropriation is an instinct rather than a discipline, though it can be developed like one. It involves a consideration of objects, images, and experiences in a range of circumstances that is intellectual and sensible yet issues from a desire to manifest new ways of thinking about art. The term itself didn’t come into popular use until the 1980’s, when artists like Sherrie Levine, Jeff Koons, and many others were manifesting separate models of the movement called Neo-Geo. Yet the standard by which these artists gleaned their attitudes had been surfacing now and then since the earliest decade of the 20th century.

The presence of the real in art, rather than the mere suggestion of it through artifice, was central to this new agenda. I propose that this was made urgent due to advances in photography and cinema. Images of real persons, places, and objects began to compete with the public’s attention not only in popular media but as a means of raising consciousness. Art circles became filled with the new language of the real as captured and portrayed in such mediums.

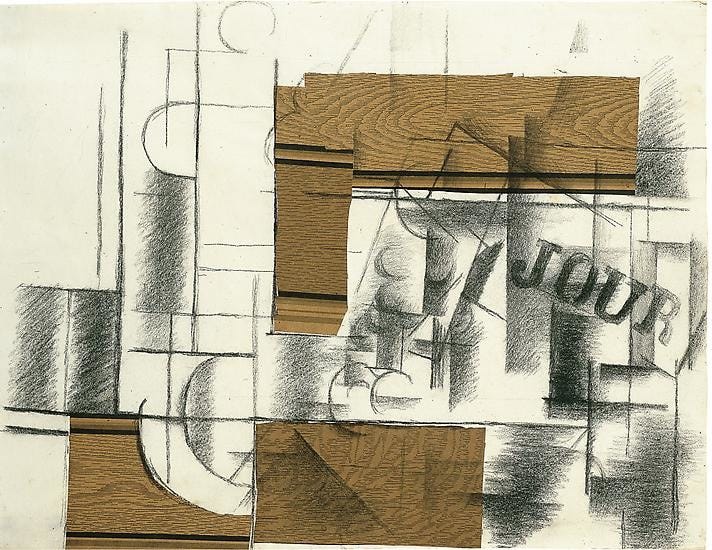

The Cubists were the first to mount a visual defense, which they achieved by utilizing minute elements of the everyday into their painterly constructions. There was no better stand in for realism than actual objects themselves to express what was needed. Having observed societal changes, and living in a moment of flux and change, artists began to recognize the charismatic appearance of materials, and how they could be used to establish new modes of encounter.

The urge to be constantly “new” drove Braque, Picassso, and Gris to progress beyond the limitations of the painted image. No matter how progressive the initial conceptions of Cubism had been, five years into its predominance on the artistic scene, it became necessary to avoid mere solutions to formal art problems, and to enter into a visual relationship with life itself. The formal digressions that were required of Cubist collage made a solid break with any and all standards of practice inherited from the past, even if that past meant the one related to these three artists themselves. What they did spread out into the creative habits, and therefore the world-view, of all other contemporary practitioners of Cubism. The use of objects or print imagery was meant as a strategic act of remodeling the nature of how abstraction operated, how it created a weft in space; the act of collaging changed the depictive quality of dynamically orchestrated spatial meaning, from a drawn and painted one with illusory depth, to one in which the use of words and the flatness of the collages papers created a previously unrecognized visual complexity that was profoundly oblique.

The Dadaists were among the first to take an everyday object and place it in the context of a work of art, without any justification. Because of Duchamp, objects like a bottle rack or a bicycle wheel can be considered aesthetically, even theoretically, as art. This objectification, this meaning mongering, was only part of the larger impact of his role as an artist. What Duchamp really wanted to do was escape the straightjacket of painting. What he did with these objects, as he did with further explorations into conceptual meaning, was to extend the purview of the artist beyond the traditional atelier and into the street or the library. Likewise, artists like Max Ernst and Kurt Schwitters created artworks of a colaged nature using only jumbled wooden objects taken from decorative household elements. The complete lack of individual justification was evidence of the madness of life. The objects of real life became artifacts of a lost civilization.

Contemporary versions of appropriation vary, though they tend to occur as part of a conceptual driven agenda. This is due to the fact that the majority of artists utilizing appropriation do so in order to construct sculptural inventions or environments. Few attempt a bare faced approach in the style of a Marcel Duchamp; usually there is some attitude or condition that differentiates them from the original object. Yet divergent models do exist, and they shine new light on the idea of appropriation as well as upon our perception of them. Appropriation uses not only the object or image, but also the appearance or manner of it, and the range of meaning that is produced by both. Historically, the appropriated object has had generationally driven exemplary models.

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) who was perhaps the most famous artist known for mixed media assemblages, developed his roving eye for unusual materials during his tutelage under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College. It was actually a classroom exercise the title of which translates as “Handicraft” and involved sending students out to gather a variety of objects in different groups according to materials. The purpose of the exercise was to reinforce the understanding that different materials held both an excess of applicable formal possibilities as well as certain conditional limitations. Despite the complexity of this circumstance, the use of divergent materials was superior to the provisional traditions toward clay or stone. It proved transformative for Rauschenberg himself. Never again was he to look upon the artistic process of reliant upon mere pigment itself. As evidenced in the many models of his signature style, The Combine, a title which references both industrial work culture and left-leaning Socialist community values, was fabricated from a combination of appropriated materials along with canvas and paint, though organized upon standing or hung constructions that almost always extended off the wall in organic gestures. Sometimes Rauschenberg would use a recognizable object as the base, as in “Bed” (1955) or a taxidermied animal, as in “Canyon” (1959).

A certain quality of esthetic encounter is present in these works that is the by-product of the zone which they inhabit, one which wasn’t fully evident to me until “Robert Rauschenberg: The Combines” was presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2005. Then I could ascertain what kind of the monumental effect appropriation had upon the art of our time, and how further examples could broaden and enrich its visual language, and provide a greater pleasure in its regard. They are Combines not because of what they are but what they do. They take formal elements like the gestures and masses of pure pigment that characterized the generation of painters preceding his own, the historical moment from which his own work was providing a necessary respite. Abstract Expressionism is everywhere in these works, it suffuses them without dominating; it is forced to collaborate with the objects he inserts into them, artifacts palpably connected to his own life “…including family photographs, news clippings about his relatives and himself, and images and objects of importance to him…These mementos—as well as pieces of windows, doors, wall coverings, and fabrics that evoke the concept of home—provide specific references to his life and art at the very moment when he was forming a public persona (Schimmel, 211). This personal hagiography was original in the practice of appropriation and also operated as a means of speaking to the past, to Abstract Expressionism, to Dada, and to Cubism. Rauschenberg brought not only a sense of intimacy into his works, but he increased the scale of them, making them feel like set pieces for a staged performance.

Conceptual art in the Eighties made a turn into an almost Pop sensibility. One artist who exemplified this was Haim Steinbach, who exhibited objects made for the home, items of clothing, and commercial souvenirs out of comic books and Hollywood movies, presenting them either on modular shelves or portable closets, bringing the common appearance of useful and well-designed objects together to create visual puzzles and oblique narratives. I attended several of his exhibitions in the Eighties and Nineties: stripped down affairs, presented as selections of specific objects possessed of a design-oriented character, such as might be seen in the MoMA design store, combined with things as simple as a pair of sneakers, three colorful boxes of laundry detergent, or a kitchy lamp with deer hooves for legs. Steinbach’s work fell into a vernacular that was contemporaneous to the era of the Eighties, called Neo Geo by some: juxtapositions of objects with a heavy dose of cross cultural symbolism, speaking not only to their appearance along a scale of high to low art, but also addressing any and all modes of interpretation, up to and including the very language used to describe it in exhibition catalogues and art magazine reviews. Steinbach was not only exhibiting objects, but was engaging in the origination of intellectual language as critical counterpoint.

Starting in the late Nineties and early Aughts, Gregory de la Haba began to document examples of graffiti, an act which ended up generating not only more than one series of formal oeuvres realized in the studio, such as his Duende and Portal series, but also one in which the act of appropriation is more direct: “[He] collages and composites six doors and entrance ways that still exist in some form around the five boroughs, all covered with years of tags, stickers, graffiti and other street detritus…” (McVey, Kurt @whyankombone) up to a second story height, replete with surface erosion and historical decoration, and then paints over them with his unique forms, or invites graffiti artists of his personal acquaintance, like EASY and KIt17, to collaborate by adding their own forms. These ephemeral landmarks, with the language of the streets, have become a project of De La Haba’s, an interpretation, an homage, and an interrogation. He considers this work not merely as innovative but also as a spiritual homage to the streets where graffiti artists have traditionally staked their claim, raising it up and placing it in direct relationship to fine arts, taking those real world details that first emerged with Cubism back into critical consideration. The commercialization of graffiti art has an inconsistent and marginal character, having been associated with few exceptions, and those few emerging either part of an underground scene like the East Village era, or in the wake of a the imminent dissolution of scenes in Williamsburg and Bushwick, or in times of great societal strife. Graffiti begins as a means of asserting a provisional self-evidence, drawing a line in the sand, staking a claim to be seen. It evolves with the development of expressive artistry, and may at times be co-opted into the commercial sphere, yet remains idiosyncratically its own order.

Appropriation isn’t merely about use value, but about the transformation of attitudes regarding the thing used. One might think of appropriation artists as strategists rather than makers. This partly true, yet what makes them interesting is how they use what they choose. In the era of the screen grab, and now of AI, what is left that hasn’t been sampled and bent to another’s purpose? What they make is a new kind of reality using the objects to which we have become so accustomed that we take them for granted. They re-negotiate the meanings of these objects, often by combining them in new ways. The selection and styling of the objects, their combination and commingling of interactive gradients of meaning, placed within a rarified visual context, creates a new experience as well as a fresh perspective.

DAVID GIBSON is a freelance writer in the arts. He is available to write essays for monographs, exhibition catalogs, text for web sites, grant and residency applications, and to provide critical thinking in matters of portfolio development, studio practice, and professional etiquette. He can be contacted at davidgibsonwriting@gmail.com