THE STORY OF THE BODY

THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF BILL DURGIN

An object is the subject that we make of it. We may say the word “Body” for instance, and imagine it depicted in a certain manner, within certain limits. This image of a body may fall within certain aesthetic parameters that have been established by academic expectations or by the use of the body in performances. However, all it takes is for us to experience the body itself in a new fashion of depiction, or a series of progressively altered versions, for our supposed idea to change. That object becomes a cipher rendering a loaded subject defined by its appearance. Like an object that is muted and then obscured either by a deepening darkness or by immense distance, we must comprehend the qualities that make it important before it fades from view.

Bill Durgin challenges us to understand bodies, and their place in the act of looking. Durgin treats the body as his canvas rather than his subject. He has been developing changing views of the body for a decade: starting with dramaturgical mis-en-scenes; moving on to ones in which the body exclaims its innate alienness, to more formal combinations of body parts in extremis played against different colored backgrounds, made by the use of plinths, that frame the anonymous viscera. More recently, Durgin commingles backgrounds with bodies, erasing them or making them seem muted or mutated by the limited means we may have for perceiving them. In these photographs beauty and desire spar with one another. They compel us to look away from a central figure that draws the eye. If we look back to his early creative development, we can perceive how he was motivated to find new ways of looking at bodies, even if it meant changing the bodies themselves. Ordinary bodies in ordinary situations could only be taken so far, because they had to inhabit specific psychological narratives. Even when twisted into perverse poses, or seen partially, what remained constant was that they belonged to people. Durgin didn’t want to present anything resembling a traditional narrative. He wanted to excavate layers of meaning from the appearance of bodies. In this he may have taken certain esthetic cues from historical precursors such as Paul Outerbridge and Man Ray, who both presented highly formalized images that used the body for its presence and as a receptacle for the release of sexual tension. This was likewise achieved by Hans Bellmer, though by remove, using objects resembling bodies in addition to real bodies. To create an esthetic radically estranged from narrative, it becomes necessary not only to stake certain claims, but to focus maniacally upon a single idea or object that is not philosophically intransigent; it can change minutely when the artist needs to alter perspective. The body’s factuality becomes fictionalized; its perception alters its very fabric. It ceases to provide merely functional or erotic roles, but merges these with whatever else is aesthetically at hand.

Durgin’s first radical move as an artist presented bodies as denatured plinths; having removed with a surgical precision all the details that denoted idiosyncrasy. What remained was the self-evidence of the body with utility and sensuousness extracted. The alienness of these reductive bodies projects an erotism that is attached less to the body itself than the attention we are accustomed to giving it, and it is a measure of this fascination that these retain. They are abject versions of full bodies, chilling reminders that without any of the characteristics that make us each individual, we might still exist like a slug or an anemone. Such pure factualness pushes us to realize the true nature of what it means to be human. They reference ancient Greek sculptures, which though fragmentary after the wear and tear of millennia, are still held up not only as examples of immortal artistic vision but also as idealized versions of human existence. Why should we accept a fragmentary ideal no matter when, or by whom, it was made?

The second move brings sensuality and mise-en-scene back into his figures. His formerly abject bodies now mine an active erotism. They are given long, lustrous heads of hair, and the spaces into which they are placed magnify the erotic and dramatic. They are accompanied with scenic objects or materials that bring a quality of mise-en-scene, and sometimes the images are split into diptychs. They are still narratively shorn of agency. We feel something about them, but not for them, as they are only a stab in the direction of dramaturgy, and do not fulfill the demands for an actual story.

The third move points specifically to formal qualities that are bound up in the dichotomy of creation and destruction, or Eros and Thanos, love and death. But again, with Durgin it’s not actual bodies that are having either done to them, except perceptually via the use of objects to obscure and fragment them, giving us the beginning of what will later come to be fully realized later on. Consistent with the first move, none of the separate works are given individual titles, but are each meant to seamlessly imply the same psychological message. One is meant to experience each image as a broadening of the degree of meaning imposed upon the viewer, like an ongoing montage with framed interruptions, like a stream of consciousness narrative that yet must undergo the separation of pages, with the interruption in consciousness moving from one page to the next will require. Depending upon how highly one becomes emotionally and aesthetically connected to the sum total of images as view contiguously, will ensure that a strong effect is achieved.

The fourth move repeats the use of surrogates. In that series, the accompanying “still life” for the most part form diptychs, in which the non-body image is an upright rather than a landscape-oriented photograph. In this series the still life becomes a proper surrogate, creating an elliptical exercise in looking. The other primary difference between these series is exemplified by the specific surrogate images, which match their bodily pairings in terms of a sort of visceral abandon. The surrogates acquire a degree of dramatic effect that connects to a visceral quality without ever quite possessing it. They can seem like bodies, or seem like characters, and can even impose bodily metaphors like damage, exhaustion, or lust.

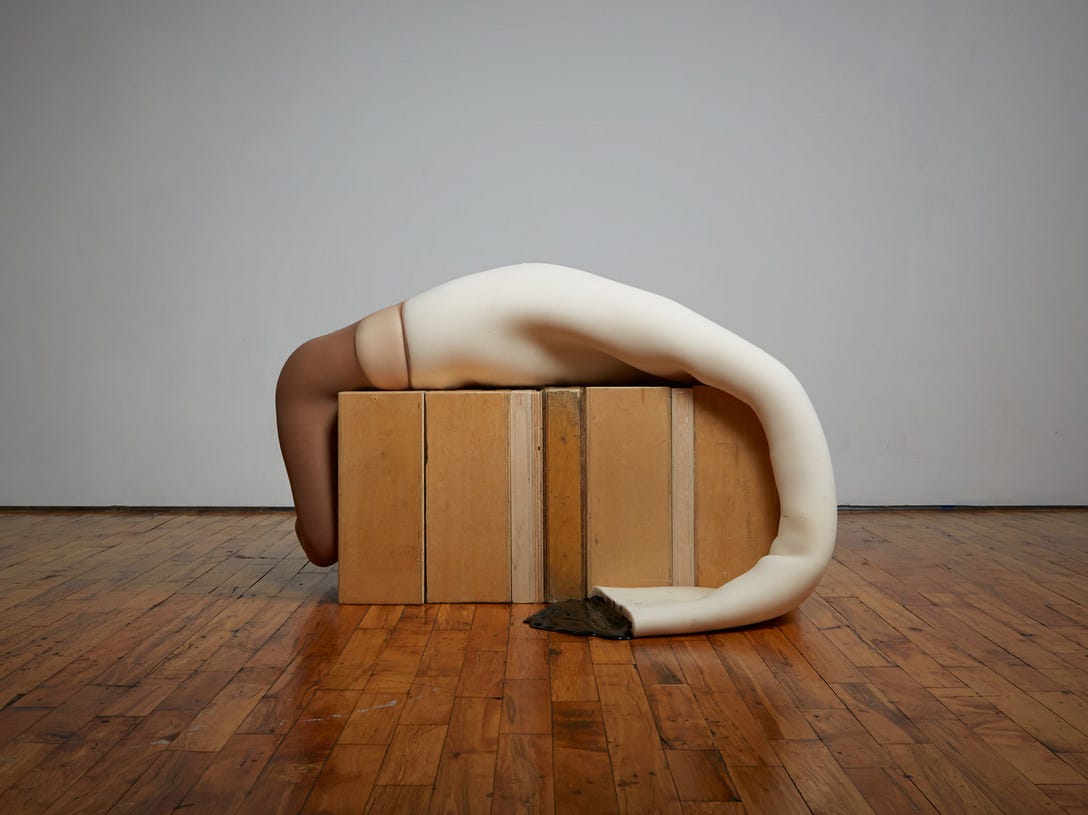

The fifth move returns to the world of delimited aesthetic effects that was the primary drive behind now chronologically distant works. The primary difference here is a formal stratagem to which Durgin will later return, the merging of the central figure with its scenic background. The two formal devices here create a swirling new dimension, where mutated bodies commingle with flattened, textural backgrounds. These are no mere plinths. They occupy a new more infinite space in which the expected range of appearances stretches like a funhouse mirror, and yet remains stoical. We comprehend them as morphed limbs, and despite how they have been transformed, we extend our aesthetic sympathies to match them.

The sixth move returns us to real bodies, as they are in the process of being perceived, studied, and obsessed over. For the first time Durgin is taking pictures of real bodies, and the bodies belong to beautiful women. Yet these are bodies deconstructed by the complexity of perception. No exercise in mere lust, the process on hand here hides some parts of them, obscures others, and leaves other parts palpably and delectably present. We have in this instance a moment that’s been waiting to happen for some time, but one which also contains signifiers of its own ambivalence. Durgin seems to be presenting the depiction of his subjects as a sort of experiment. They present as hybrid reflections. For these are bodies in the commonplace sense—objects meant for delectation, separated from mere utility. They are placed upon a pedestal, or under a magnifying glass, or before a camera lens. All of these manners of portrayal place the body, especially a female body, in the same rarified context.

The seventh and most recent move, which is still ongoing, has to do with the grounding of the figure, or any form disposed as such, into a variable field of perception. Figures become silhouettes that exist as a kaleidoscopic mélange of partial shadows, always just around a corner, appearing to offer agency or mystery, and often, a taint of desire. It's Durgin’s subtlest work, and with the most potential for formal achievement. It started with only female silhouettes but has begun to include male ones too, some of them his own body. Their specific discipline, which obscures specific details, also allows him to inhabit his own images.

I call Durgin’s progressive formal developments “moves” because they remind me, alternately, of the stratagems in a chess game, and also the gestures in a dance performance. Both require a shifting of perspective, and a growth beyond original perceptions of what is necessary to succeed in a given arena. Of course each of his series is possessed of a title, and these titles bestow upon them both authority and mystery at the same time. After the long consideration that has produced this essay, I find myself less interested in confronting these titles, of explicating and comparing them, than I am in the visual and visceral aspects of the work itself. I feel that the experience of these qualities constantly enriches the understanding of meaning in his work, which is involved in telling a story about the body, a story that alternates between reality and alienation, between theatre and analysis, and finally, it opens up into a broad expanse where anything is possible. Looking back upon all these oeuvres, I imagine them as diverse landscapes in which similar figures are shaped by alternating expectations. One travels amid them to experience what is unique to each. I find them each compelling and worth revisiting in the future. This essay was only the beginning of the adventure.