Tracking The Marks of Memory

ABSTRACT INTENTIONS

Anyone who has lived long enough to have moved out of their childhood home, or who has had to pack up and abandon an older family home, will have memories to match the portent spilling out of the art works of Amanda C. Mathis. Anyone who has also walked through an old boarded up house, or seen a beloved structure being torn down, and has walked through or looked into similar dead corners, will likewise appreciate what Mathis achieves in her work. The spaces we live in are imbued with a special character, partly the emotional detritus of a life lived, and partly the potential for future events over the passage of time that will leave their own detritus.

In large cities a structure can stand for a century, but eventually it will lose its usefulness, and be replaced with a different structure. This is the story of a city. Towns change less frequently though always there is the slow drift of generations into different parts of the same communities, or farther in one’s country, as we are moved by world events and by our own urge to discover new spaces. Americans are by nature travelers, and it’s in travel that we find out how to be the same people but different. We return to our homes, if and when we return, to deposit some quality of our character there. Perhaps we bring objects with us, or people.

We create what Amanda C. Mathis calls ‘memory markers,’ puzzle pieces in the background of any home that together accrue a sentimental or nostalgic degree of personal importance, even though they are only the background color (the forms or the details that fill in our memories and our dreams) of the idea of home. Unearthed and recombined as they are in Mathis’s work, which alternates between two-dimensional paper collages, mixed media sculptures, and in-situ installations that create mutated, extreme versions of the concrete and tactile elements that typify our experiences in such spaces. However, the encounter we have with her artwork alters according to its scale, its apparent degree of artifice, and the degree of immersion into real spaces where it takes us.

We all have a relationship to structures, both our own homes, whether a house in the country, an apartment in a building, or the other structures that make up a community, including shops and markets, post offices, banks, and churches. Each type of structure leaves us with a range of impressions and affects us in different ways. We learn what sort of structures attract and repel us, both outside and inside them, and to a greater degree, how our choices will affect others. In a large city like New York, these encounters are magnified and accrued in a short period of time. One judges not only individual structures but entire neighborhoods by the quality of their observations. This relationship to form, and to the details making up form and space inside buildings had a profound effect upon Amanda C. Mathis and formed the basis for her origins and growth as a contemporary artist. The dimensions of space in life versus in art diverge in perspective. Space in a city is everything. The scale of buildings and roads in different parts of the city alter our bodily and personal relationships on an ongoing basis.

What has informed and animated Mathis’s work from the beginning is an exploration of interior spaces, both as living and working spaces. No space exists that was not originally meant for some purpose within a community. Every space that was ever something rose from the emptiness of the land itself. Every town that later became a city was at some time in the past nothing but fields, trees, and air. Every space that now exists had several lives of its own. The buildings and streets that now exist, inside of which people have worked and lived, are in themselves the umpteenth generation of the communities that began a century or more ago. So for the artist to depict empty spaces, stripped down and punctuated spaces, is not only to deconstruct the space itself, but to speak of its beginnings. To plumb the emptiness inherent in any space is to speak of its further potential. It could all be reduced to rubble one day, then air, then something new. That’s the nature of progress. Someone accustomed to such radical change could only have witnessed endless similar change in their own community at an early age. This attention to rupture and flux is a practical emotional muscle, for it allows the bearer to manage future change easily.

Mathis began her exploration of spaces with an affinity for the Conceptual Art era, typified by artists like Dan Graham and Gordon Matta-Clark. What resulted from them were transgressions in space, in the land itself, and in actual built spaces like homes and warehouses. Matta-Clark split floors and walls of industrial buildings to open up gargantuan interior spaces. He had shared affinities with Land Art peers, but chose to avoid the vast wastelands of the American West and focus his radical energies upon built structures in rural and urban areas. Mathis wanted also to be a shaper of space.

The discipline of space-shaping has a legacy to it that is primarily contemporary, having altered the perception of reality on its face. This space is both actual and intellectual, and its shaping results in experiences rather than objects, although some objects are necessary in order for the realization of the shaping itself to be perceived. Although Mathis realized some decisively radical versions of this shaping in her early works, there was a limit to their efficacy. Too many similarly emphasized moments creates a vacuum. Mathis would have to serially engage similar or new spaces in the same manner. She decided to run away with the idea of space, taking it into areas that she confronted and recreated through an excavation of the layers of utility beneath commonplace surfaces. Mathis chose to rip away exteriors to expose the void behind them, which in some cases exposed forgotten decorative layers.

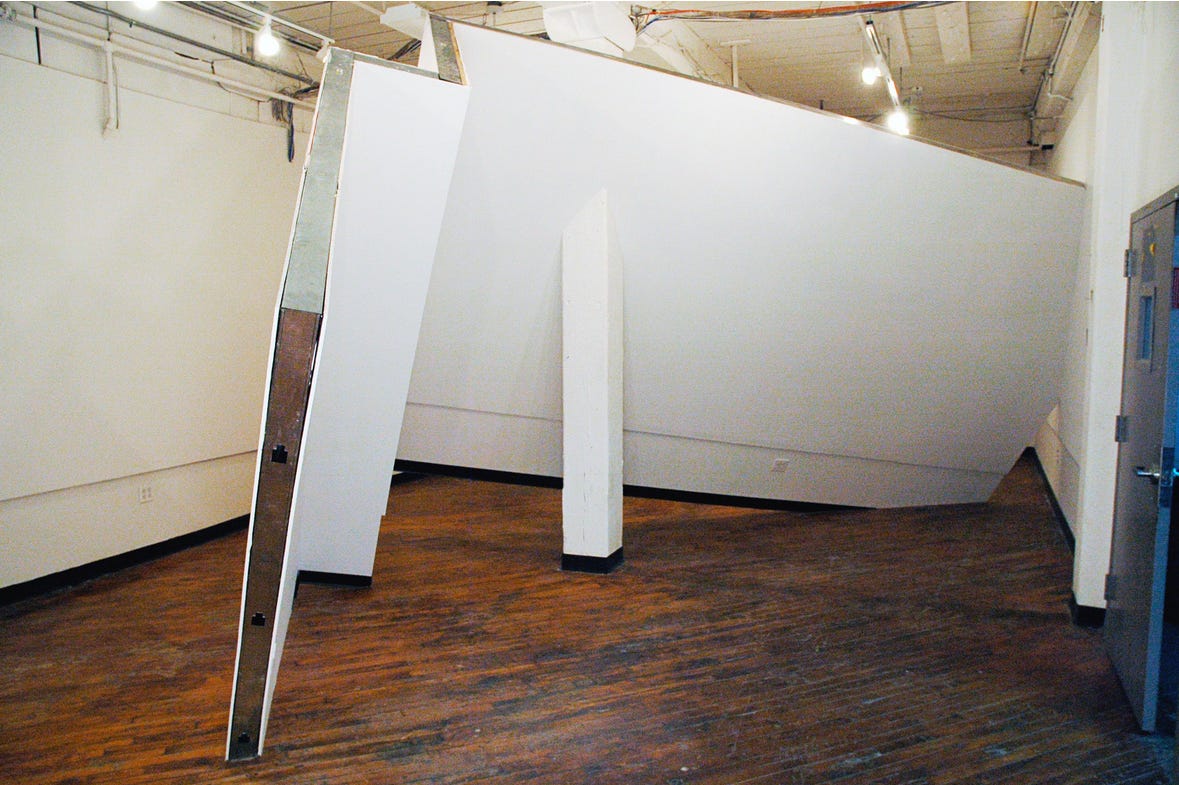

In 2006, Mathis started creating false walls within actual rooms; first, within the studio building where she was attending graduate school; then in various other blank spaces; and finally as a monolithic sculpture in a gallery. Her works were expressive. They did more than form a room or hold up a ceiling.

In 2008, Smack Mellon invited her to create a site-specific installation inspired by the industrial history of the gallery itself. The accomplishment of this art work, which was monolithic in contrast to her previous in-space constructions, served to redefine her understanding of how architecture could model as presence, or as evidence of agency. It was her deconstructed aesthetic on display as art rather than as transgressive architecture. The logistical difficulties it presented showed her that her wall-as-art idea had run its course. If this was the sort of work that all her previous and then current wall projects aspired to be, then the idea was done. Mathis does not seek myopic repetition of her ideas beyond their usefulness.

Mathis’s second series of installations were more purely a series of excavations, in which she stripped linear sections out of walls and floors, revealing the void of nothingness between them, and the recently unseen layers of older walls and floors that played out as decorative. These smaller rooms were in preexisting spaces that has been used for offices and work spaces. These works were likewise connected to the spaces where they originated, and only documentation remains to show us how successful they were.

In 2012, Mathis switched from commercial to residential spaces. She found empty homes and worked with materials on site to arrange and construct new experiences that played fantastically with the still beautiful qualities of decorative things like rugs and curtains, once purchased to prettify a home, but that had sunk into functional normality. It was the first time that Mathis had engaged with the domestic sphere, and all the personal associations it carried. Her “memory markers” are not physical details but the emanation of past lives that pulses from objects in these abandoned homes, and any photographs of them that yet exist, providing a visual context for these decorative and functional elements of a place once called Home Sweet Home to be relived. Despite their ruined stasis, these places cannot help but affect the viewer, who will compare or contrast them to other memories. Looking upon them myself, I do not see the home I grew up in, but the homes of elderly relatives out of my childhood, and the homes of friends from my youth, some of the them in apartments very close by to my own. The shag carpets, the flowing curtains, the sconces—all of these shout home, home as palace, as nest, and as bower. They are in their dilapidated state a homely yet endearing ruin of our past lives, a testament to the qualities that our parents and their friends brought to the domestic sphere.

Following these manicured ruins, accentuated in some cases by efforts of the artist herself, Mathis began two series in 2013 that are currently ongoing: smaller, self-hanging or standing mixed media sculptures, and two-dimensional collages that play with a similar range of visual collusions. Both series combine interior and exterior appearances, with all the connections to epoch, class, and community by which they are recognized. They were her works that I first discovered, and which led me back toward all the other works and periods of which I have been speaking. Despite being small in scale and constructively more fragmentary I find them no less powerful; and in many ways more accessible, not only as an expression of her métier, but as a direct means of expressing what constituted the qualities of her prior installations and constructions, while requiring less investment in previously existing spaces. Her ability to construct them speaks to the informed basis of her past work as a process by which she can now manifest intimate experiences. The collages are particularly compelling for the way in which they combine type of imagery that, though it connects to cultural associations with types of architectural detail, it contracts and pulses with the life of images culled from domestic interiors, so that a pure romanticism, though strong, can never completely hold sway. It is always pulled down into the loaded interior territory described with images of linoleum floors, shag rugs, and lace curtains. The commingling of implied textures paired with the documentation of wear and dust create a narrative into which the viewer can project their own self. Despite the alternation of surfaces in a combined collage, they not only come off as real and true, but as lyrically impactful. We see the images bit we also feel them deeply beyond intimations of sense-memory. They memorialize and dramatize our nostalgia for things we both had and never had; memories experienced only in passing, as we watched our neighbors and wondered what their lives were like.

The small sculptures that Mathis now also makes are different from the collages in that they flirt with flights of fancy and lunacy while rooted in objects that remain connected to a nostalgic past. Separated from their original environment, these tchotchkes become totems which then, having undergone a process of formulaic revision and reimagination, populate our perception with new aesthetic events. There’s a whole history played out in the progression between Mathis’ creative intervals, in which ever more complex and loaded environments are eventually reduced to objects and collages imparting an original specialness. These new works can be placed anywhere and emanate the virtues of a lost life. I would like to see them in historically rarified settings, either real houses or period rooms in museums, projecting their charismatic idiosyncrasy, creating new memories to mark time.

excellent